Storm Warning

Nov. 22, 2005 — -- Despite the wishful thinking of the feathered inmates in the movie "Chicken Run," chickens can't fly more than a few feet. Yet, in a way, chickens may now pose the biggest threat to those who do -- the indispensable American public utility known as the airline industry.

Asian chickens, to be exact, the ones infused with a percolating biological threat known as virus H5N1, or bird flu. Having essentially no previously developed natural resistance to the strain, our human species is extremely vulnerable to the nightmare of H5N1 mutating into an easily transmitted form of human flu, and the estimates of deaths from a potential worldwide pandemic are variable, but terrifying overall.

A few years ago I personally created a really bad Level IV virus (aka pathogen) and put it on a 747 leaving Frankfurt just before Christmas to kick off one of my fiction stories in the book "Pandora's Clock." That virus (which, blessedly, was the construct of a fiction writer's application of science to possibility) doesn't exist, although hideous diseases with guaranteed death rates above 80 percent, such as the monstrous Ebola Zaire virus, do exist. The point of "Pandora's Clock" was that most developed nations have a deep and legitimate fear that when a real viral killer emerges somewhere in the world, the modern jet airliner will provide its ticket to attacking the mass of humanity within days, and we're nowhere near prepared.

It's not just Americans who have a bad habit of closing the barn door after the horses have escaped. Waiting until a crisis is upon us to prepare for it is a very human trait, especially acute in bureaucracies that thrive on order and predictability and can be easily overwhelmed when nature or circumstance goes off-script.

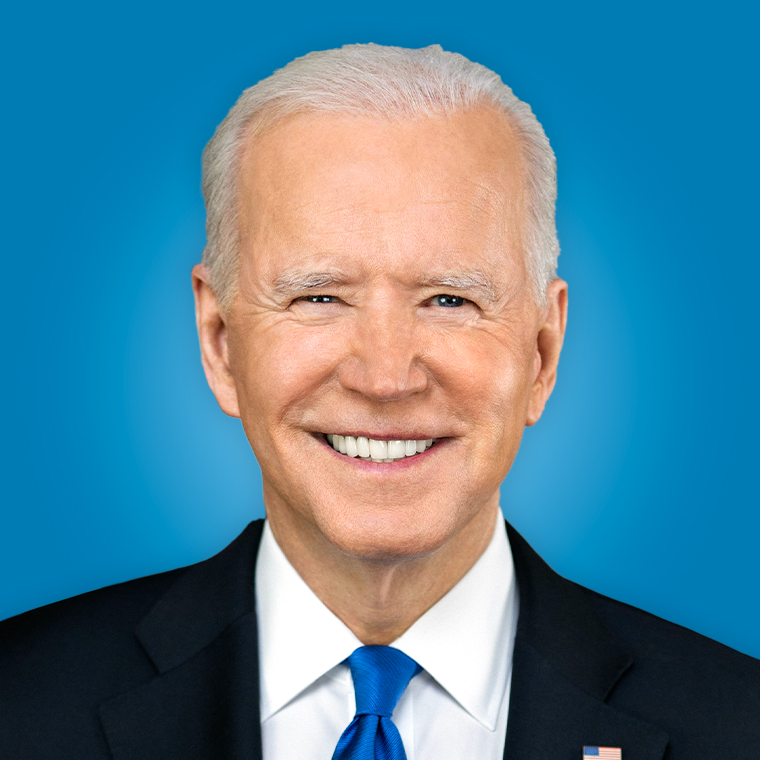

For jarring proof of this, we have only to point to FEMA's performance in the face of (and the wake of) Hurricane Katrina. But while even President Bush is legitimately worried about how to contain the terrifying possibility of a sudden outbreak of H5N1 in North America by just using a few excellent but already overburdened agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Pentagon, avian flu still has the potential to all but destroy the U.S. airline industry.

Plainly put, if a pandemic breaks out internationally, a staggering percentage of current international travelers will simply stop traveling and wait it out. But if a pandemic hits the United States or Canada, North American airports and airlines -- the prime transmission points -- will stand largely abandoned while authorities struggle with quarantines and containment. Bottom line: not even the perennially profitable Southwest Airlines can survive such a financial disaster for long.

The reality is that, like it or not, airline deregulation (enacted by a bipartisan Congress in 1978) has been one of the great disasters of the American Experience, and the proof of that is self-evident in the destruction of so many airlines and the current bankrupt status of United, Delta, and U.S. Airways. Even in Chapter 11, Delta, for instance, is hemorrhaging billions of dollars annually and eventually the well will run dry.

Why all this has happened is the topic for another column. The reality that even the strong among U.S. airlines are vulnerable to sudden spikes in fuel prices, let alone sudden abandonment of passengers, is essentially unquestioned.

Fleets of jetliners with price tags of between $40 million and $200 million each and costing literally millions per month even to lease cannot be left parked on the ramp for more than a few days before an airline financially melts down. After all, in the wake of 9/11, the losses among all U.S. airlines from spending several days on the ground and many weeks with partial loads of worried passengers amounted to enough money to worry Bill Gates (i.e., billions).

Even a government bailout program only plugged some of the holes in the financial hull of most carriers, and even with that help, the massive retardant effect of SARS the next year helped march the legacy carriers into bankruptcy court (and kept those already there in tenuous condition).

The impact of public abandonment of public transportation in the face of a spreading pandemic in our own back yard, however, would simply collapse the delicate financial structure of most carriers who depend on a river of cash coming in, as well as flowing out of, the door. Cut off the inflow and the rest of it dries up.

"So what?" the worst of the blind supporters of deregulation respond. If all the airlines collapse, others will rise in their place. In theory, of course. In fact, more than just passengers depend on the ability to get ourselves and our goods from Point A to Point B on demand. So does the economy. Again, the post-9/11 experience validates this.

The purpose of all this is not to frighten, but to raise a clarion call that among the other nightmarish elements we and our elected officials absolutely must carefully consider and plan for is the role of the airline industry as an indispensable part of American life (read: public utility), and we must prepare for what we'll do if the worst occurs.

The vermin who attacked us on 9/11 are betting we'll get it wrong.

John J. Nance, ABC News' aviation analyst, is a veteran 13,000-flight-hour airline captain, a former U.S. Air Force pilot and a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserves. He is also a New York Times best-selling author of 17 books, a licensed attorney, a professional speaker, and a founding board member of the National Patient Safety Foundation. A native Texan, he now lives in Tacoma, Wash.