Losses from Michael could be close to $10 billion. Insurance companies prepared with record funds

Insurance industry experts project losses to range from $8-$11 billion.

Insured losses from Hurricane Michael will probably be in the vicinity of $8-$11 billion, according to experts in the insurance industry and academia. They put the overall economic impact in the range of $30 to $40 billion. That number includes lost economic activity, the expense of first responders, uninsured losses and infrastructure repair.

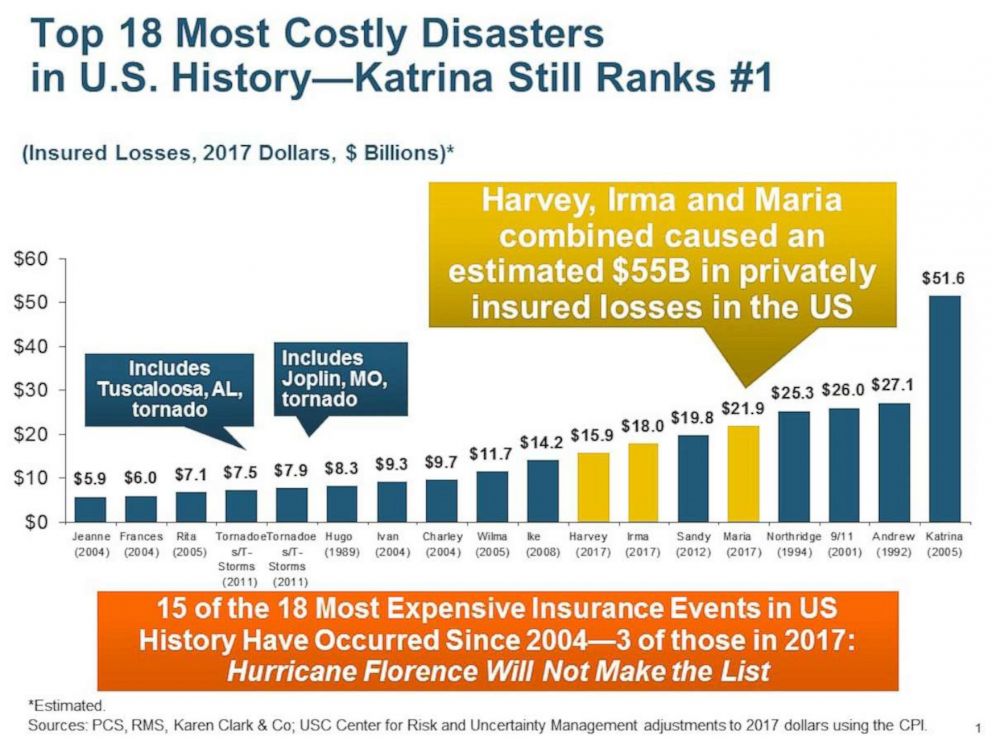

If that projection for insured losses holds, Bob Hartwig, who teaches financial risk management and insurance at the University of South Carolina, says Michael would rank as the 11th costliest insurance disaster in U.S. history on a list he compiled from industry sources (topping that list is Hurricane Katrina at nearly $52 billion).

While Michael is horrific and devastating for those in its path, there's some measure of good fortune in the eye-popping numbers that may be associated with it.

It could be much worse.

“If there is a silver lining here, it’s the fact that where Michael came ashore and where it went inland, these areas are not particularly densely populated relative to most of the coast of Florida," Hartwig said. "If it had hit Miami or Tampa, we’d be talking something quite different here.”

Also, as catastrophic as the damage is, the insurance industry is unusually prepared to cover it. As hurricane season began, Hartwig notes that insurance companies “collectively held a record $761 billion in capital for paying claims. So, they entered the 2018 hurricane season with financial strength that was unparalleled in history.”

The combined losses of $2.5 billion from Florence and potentially $11 billion in claims from Michael are only a drop in that huge pool of coverage cash.

This is in contrast to last year when Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria wrought $55 billion in property losses (as shown in the chart above) and insurance companies tapped reinsurance funds to help cover them.

As people in the path of storms like Michael seek protection from their ferocity, insurance companies do the same.

Local or regional insurers may not have the capital necessary to cover all the claims from a huge disaster. So they protect themselves by buying reinsurance, which draws from a much larger global pool of funds.

One avenue to that money is through a market for investment products collectively called insurance-linked securities, or ILS, a market valued at close to $100 billion, according to Steve Evans, editor-in-chief of the reinsurance industry newsletter Artemis. Catastrophe bonds (or cat bonds as they are called in the business) are perhaps the best-known example of these.

Cat bonds are issued by insurance companies or municipalities (through investment banks) to help cover the cost of a disaster. Investors buying them collect interest for the usually short life of the bond. But if there’s a disaster in that time that meets agreed-upon criteria (such as severity level or insurance losses), the investors lose their money to the issuing entity who uses it to pay claims.

These bonds are often issued seasonally or annually and not linked to any specific disaster. But insurers can still find additional capital when a catastrophe is about to happen and even after it’s over.

If insurance companies fear an approaching hurricane, for example, will be more destructive and costly than predicted, they go looking to buy “live cats" or contracts for additional coverage that they collect if the catastrophe (cat) reaches an agreed upon level of magnitude or of losses.

If the magnitude, or damage, is less than that “trigger," the issuers of these contracts keep the buyers’ money. The market for these live cats activates when a storm like Michael is still in the water (a “live event”) and may last until right before it makes landfall.

“Dead cats” are contracts for reinsurance that insurance companies buy after the storm has struck and before final damage assessments come out. Again, the notion is that the destruction will be more than what was forecast and insurers want more capital to cover it.

Altogether, this market featuring cat bonds, live cats, dead cats, and other insurance-linked securities covered around $15 billion in claims from the trio of Harvey, Irma and Maria last year, according to Evans.

ILS trading has not been especially active with Michael or Florence, yet another indication that insurers are well-prepared with the cash they already have on hand to cover the insured victims of these major storms.