3 female Olympians pledge to donate brains for concussion research

The athletes are retired top hockey players and a bobsledding champion.

— -- U.S. Olympic bobsledder Elana Meyers Taylor is in Pyeongchang preparing to compete in the 2018 Winter Games, but she said a concussion three years ago nearly ended her career.

Meyers Taylor, along with two other Olympic athletes, has pledged to donate her brain for concussion research, becoming one of the most-high profile Olympic female athletes to do so.

"The long-term consequences of brain trauma are a major concern in sports, and I’m doing this for every athlete that will follow in my footsteps," Meyers Taylor, 33, said in a statement released by the Concussion Legacy Foundation, a Boston-based organization that advocates for the study, treatment and prevention of the effects of brain trauma, particularly in athletes.

Joining Taylor in pledging to donate their brains for concussion research are four-time U.S. Olympic ice hockey player Angela Ruggiero and Hayley Wickenheiser, a five-time Olympic medalist for the Canadian women’s ice hockey team.

Ruggiero, 38, chair of the International Olympic Committee Athletes’ Commission, said she saw teammates lose their careers due to concussions.

"I saw teammates around me that literally lost their career or had to retire early, prematurely, because they had major, major concussions," said Ruggiero, also CEO of the Sports Innovation Lab. "I thought I could potentially be a good role model for other athletes."

The women's decision to make the pledge, and to do so publicly, shines a much-needed spotlight on the topic of females and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), according to Dr. Chris Nowinski, co-founder and CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

“This has always been an important topic for female athletes but because football has received the most coverage, females don’t get enough attention,” Nowinski told ABC News. “A female athlete has yet to be diagnosed with CTE but that’s primarily due to [not having] many female brains donated.”

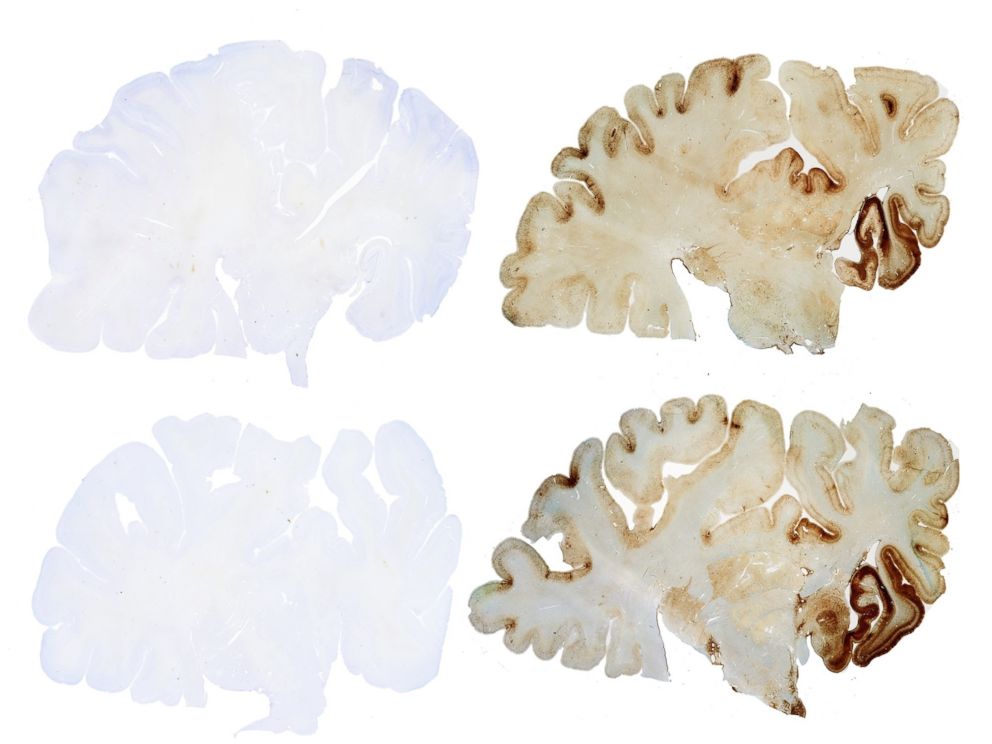

CTE is a delayed neurodegenerative disorder that develops as a result of repetitive mild injury to the brain, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIDDK). Right now, CTE can only be diagnosed postmortem.

'There is no question female athletes are susceptible'

Of the more than 2,800 former athletes and military veterans who have pledged to donate their brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation since 2008, a little more than 560 are female brain pledges. Fewer than 10 female brains are currently in the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, the world's largest.

"We can’t even begin to explore sex differences until we get the brains of females with CTE," said Nowinski, a former wrestler who was inspired by his own experience with concussions. "We haven’t had that first case of CTE in a prominent female athlete that opens up everybody’s eyes."

Nowinski said he notices in his own experience calling families to request brain donations and pledges that family members are less comfortable talking about the brains of their mothers and sisters going to research than those of their brothers and fathers.

"We hope these pledges today help change that concept and make it also normal to donate female brains," he said. "There is no question female athletes are susceptible and this is an important area to investigate."

Other prominent female athletes who have already pledged their brains to the foundation include U.S. soccer legend Brandi Chastain, former USA Hockey Women’s Player of the Year A.J. Griswold, and three-time Olympic gold medalist Nancy Hogshead-Makar.

When Chastain pledged her brain, she began working with the foundation to introduce a minimum age of 14 for heading soccer balls, according to Nowinski, who added it's "exciting" to see the national conversation about concussions and kids and contact sports begin to shift.

CTE risk runs high in sports for women too

Though most of the attention and research on concussions and CTE has focused on football, the most high-profile contact sport, the risk runs high in sports for women too, like soccer, boxing, ice hockey and, as Meyers Taylor's experience proves, bobsledding, according to Nowinski.

"Bobsledding is certainly underappreciated and Elana has taught me a lot about what bobsledders go through," he said, explaining that Meyers Taylor, who was not available for comment, reached out to the foundation on her own to make her pledge.

Female high school soccer players have the highest rate of concussions of any sport, even more than football players, according to a study presented at last year's Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). Around 300,000 adolescents suffer concussions, or mild traumatic brain injuries, each year while participating in high school sports, according to the AAOS.

CTE can occur years after the brain has experienced trauma. Symptoms of CTE include memory loss, mood changes or even suicidal thoughts. According to the Boston University CTE Center, there may be some similarities between Alzheimer’s disease and CTE.

A recent study from the same group found that repetitive hits, even those that do not result in a concussion, might still lead to the development of CTE.

The Concussion Legacy Foundation is now also accepting pledges for the brains of non-athletes and non-service members to serve as controls in CTE research. February is Brain Pledge Month.

"We’ve learned CTE is going to be incredibly hard to treat so we need continued momentum," Nowinski said. "We’ve also learned that it’s incredibly easy to prevent. If you are not hit in the head, you won’t get CTE."

Dr. Sarang Koushik contributed to this report.