Top 7 Celebrity Drug Endorsements: Commercial or a Cause?

Despite debate, drug companies pay celebrities to hype disease awareness.

April 1, 2009— -- People love their celebrities and advertisers love their power to sell virtually anything: makeup, clothes, sports drinks, even remedies for irritable bowel syndrome.

For years celebrities have traditionally sold products such as cars, perfumes or financial services. Others have used their fame to help non-commercial or political causes such as ending wars, poverty or illiteracy.

But in recent years, many celebrities have found a controversial new way of making money: raising awareness of serious public health issues in arrangements that often include indirectly endorsing over-the- counter or prescription drugs.

Public relations specialists and drug industry watchdog groups have long debated whether discreet ties between celebrities and pharmaceutical companies are beneficial or harmful.

"It's like anything else; you don't have to listen, you don't have to take this drug, you don't have to see this particular doctor," said Amy Doner, founder of the Amy Doner Group, a celebrity-pharmaceutical consulting company.

Doner says she has connected Cindy Crawford, Anjelica Huston, Sally Fields and others to pharmaceutical companies' drug advertising campaigns. She said at the very least, the celebrities may inspire people to get more screenings and checkups for common and often treatable medical conditions.

"They're really there just to urge and encourage people who may not otherwise get up and do those things," said Doner.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration strictly regulates information in drug commercials, but a celebrity raising awareness about a disease is a different story. During an interview or a news conference, or even on a television commercial, celebrities are free to talk about a medical condition with few restrictions -- even a requirement to name the drug company funding their speech.

"It's perfectly legal; it's just completely immoral," said Dr. Sidney Wolfe, director of the Public Citizen Health Research Group. Wolfe worries that patients will ask for a pill because the celebrity appealoutweighs the side effects or risks.

"It just keeps happening over again," he said.

Indeed, other industry watchdogs worry about what the campaigns can do to a person's understanding about a disease, not just a drug.

"With a lot of the diseases there is some genuine feeling at the heart of it, but what happens is that the celebrity gets hooked in and start spouting some of [the] exaggerated claims that the drug companies use," said Alan Cassels, a drug policy researcher at the University of Victoria in British Columbia and author of the book "Selling Sickness."

Cassels said he often sees exaggerated phrases like "millions of women have" or "millions of men" when someone is raising awareness for a fee.

"They exaggerate what I call the prevalence," said Cassels. "Another name for that is disease mongering."

Even when not exaggerated, Cassels said at the very least, it can be hard for an audience to tell the difference between a clear-cut disease awareness campaign and a campaign funded by a pharmaceutical company.

For better or worse, the following is a short list of celebrities who have used their fame to raise awareness for a disease and have received fees from a pharmaceutical company.

Marcia Cross, who plays Bree Van De Kamp on ABC's "Desperate Housewives," has a ways to go to catch up to U2's Bono on the cause front, but in the last few years she's made some strides to get there.

Cross has most recently championed child hunger with UNICEF, and in 2008, she testified before Congress to mandate longer hospital stays for women after a mastectomy, ending the so-called "drive-through mastectomies," according to press releases.

The actress also raised skin cancer awareness in a campaign funded by Proctor and Gamble, and in 2006, she went on a mission to let people know about how she used to suffer from migraines.

GlaxoSmithKline, makers of the migraine medicine IMITREX, funded her role as a spokeswoman. However in resulting media coverage, Cross focused much more on describing the pain and the triggers than a strong pitch on the drug specifically.

"Most people -- and I hear this a lot -- they'll say, 'Oh I have a migraine,' and I'll ask if they take medication," Cross told the Los Angeles Daily News in 2006. "It's so easy to ignore it because it just goes away. You forget about it and think you don't have it. I'm not even sure I did until I was diagnosed."

Cross declined comment for this article, but GlaxoSmithKline responded with a written statement.

"Well-known individuals, who have a health condition and can speak from personal experience, can be very effective in bringing attention to a specific disease and motivating patients to visit a professional to discuss the disease and treatment options," wrote Robin C. Gaitens, a representative for GlaxoSmithKline. "Often these conditions are underdiagnosed or undertreated and can be disabling."

In 2002, the media got wind that film legend Kathleen Turner's campaign for rheumatoid arthritis was underwritten by Wyeth, the manufacturers of Enbrel.

Turner had appeared on "Good Morning America" that year and mentioned her personal struggle with the painful and degenerative condition. During the interview, Turner directed viewers to a Web site to learn more about the condition, but only later did it come out that Wyeth ran the Web site, according to reporting by Salon.com.

Turner's publicist said she was unavailable for comment on the article.

At issue wasn't necessarily the connection, but that Turner and Wyeth had failed to tell the media outlets she had a financial tie to the Web site. Soon after, Time Magazine, editorials in medical journals and other publications questioned the medical ethics of paying Turner and other celebrities in discreet drug advertisement campaigns.

"What I think is that it crosses a bit of an ethical barrier when you don't know when a person is on the payroll," said Cassels. "It's one thing to be a spokesperson, but tell people that you're being paid."

The same year that Turner faced criticism for her unpublicized link to Wyeth, actress Lauren Bacall went on NBC's "Today" show to talk about macular degeneration -- an eye disease that can lead to blindness.

Just like Turner, Bacall failed to mention during the interview that the drug company Novartis, maker of the macular degeneration treatment Visudyne, had paid for her awareness work. Unlike Turner, Bacall did not suffer from the disease. Instead, Bacall was speaking about a close friend, according to reporting by Time magazine.

Bacall's publicist also declined comment for this interview and a representative from Novartis did not offer a comment.

Although Bacall was one of the first to be noticed by the media at large, Cassels said drug companies have been using creative marketing techniques for generations.

In the 1960s a doctor named Robert A. Wilson toured the country with his buzz-generating book "Feminine Forever." According to Wilson, women could reap illustrious health benefits and never face the struggle of menopause symptoms by taking hormone replacement therapy long after menopause.

"It was later found out that he was on the payroll of Wyeth," said Cassels. He added that he interviewed Wyeth and other drug companies for his book and that each link was confirmed.

During the heyday of NBC's "The West Wing," star Rob Lowe did an array of media spots in magazines, in videos on the Web and in interviews to champion awareness for a little-known but severe side effect of chemotherapy called febrile neutropenia.

However, Lowe didn't spend a lot of time explaining the new drug -- Neulasta, made by Amgen -- that had recently hit markets to treat the condition.

In a short spot in People magazine, Lowe described the difficulty he experienced as various family members went through cancer, including his mother and grandmother. The magazine only briefly mentioned "a biotech company" that hosted a Web site with Lowe's videos.

Messages to Lowe's publicist were not returned. But Doner, who brokered Lowe's deal with Amgen in 2002, noted that celebrities are restricted from describing a drug if they have not personally taken it.

"There are FDA guidelines surrounding the issue -- unless the celebrity has personal experience with the drug," said Doner. "Unless that's the case, they're just talking about general disease awareness and would be paired with a medical expert who could talk about the treatment options. I would say more often than not, you're pairing the celebrity with the doctor."

Before the age of celebrity drug endorsements, both open and unpublicized, Doner said that pharmaceutical companies relied mostly on trade journals or through medical journalists.

Then around the mid- to late 1990s, according to Doner, pharmaceutical companies began to turn to celebrities, especially after their newfound freedom when direct to consumer advertising laws loosened.

"All of a sudden you could find yourself on 'The View' or entertainment magazine," said Doner.

Along with the newfound buzz came a string of celebrity awareness campaigns for conditions that normally wouldn't see the light of day on TV news -- erectile dysfunction or irritable bowel syndrome, also known as IBS.

In 2000, "Frasier" TV star Kelsey Grammer who played Dr. Frasier Crane for nearly 20 years began to talk about his wife's IBS. In an article in USAToday, the journalist mentioned that Grammer was inspired to speak out after Camille received tremendous public response when she mentioned IBS during a radio interview.

However, the Grammers were a client of Doner and were reportedly also part of a campaign for the new IBS drug Lontronex, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline.

A publicist for Grammer said he could not comment because his wife, not the actor, was part of the campaign.

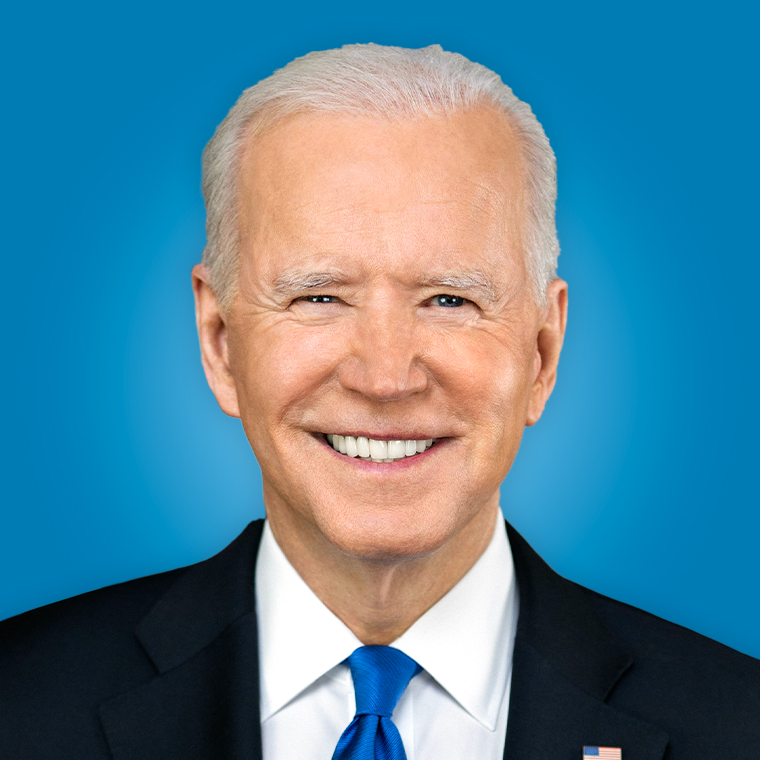

Former presidential candidate and U.S. Sen. Bob Dole was one of the most memorable spokesmen for a medical condition.

In 1999, Dole informed the country in a national ad campaign about his erectile dysfunction (which resulted from treatment for his prostate cancer) and urged men across the nation to seek help if the condition bothered them. However, Dole did not mention directly the newly released drug Viagra or Pfizer, the company that was paying for the campaign, according to a 2004 essay by Ray Moynihan in the Public Library of Science. Dole's press secretary did not return messages for comment.

In the same essay, Moynihan cited research that such awareness work can run a fee of $20,000 to $2 million. Doner, who did not represent Dole, said the fees range from $10,000 to $1 million.

"While they are being paid -- and it's work, they should be compensated -- I can assure you their sincerity was completely evident from day one," Doner said of her clients.

As the media have grown savvier to the celebrity and drug company connection in campaign adds, Doner said she has had to spend more time finding a suitable face for a campaign.

Take, for example, actress Cybill Shepherd. Shepherd has been in the public eye since the 1970s, first as a model and then as a film and television star. With a well-planned campaign, coverage of the beauty's irritable bowel syndrome hit the Boston Globe, The Miami Herald and MSN. Shepherd's publicist also did not return messages seeking comment.

Just as with other celebrities, Shepherd was also receiving a fee from Novartis, maker of the IBS drug Zelnorm, according to Doner, who represented Shepherd.

"I think that there were definitely times of skepticism and cynicism: Why are celebrities doing this and are they just paid and doing this for money?" Doner said of her business.

Despite the recent criticisms, Doner thinks celebrities' selling power will keep drug companies interested in awareness campaigns.

"As long as Hollywood is out there, the campaigns will never go away," she said.