Top Eye Expert Optimistic About Gene Therapy Cure for Blindness

The National Eye Institute director sees promise in a new gene therapy.

May 2, 2007— -- A top eye scientist at the National Institutes of Health has called a new procedure that uses gene therapy to correct a condition that leads to blindness "an exciting development" that could pave the way for additional gene treatments for blindness and other conditions.

But some ophthalmology experts remain skeptical. And with months remaining before the procedure can be declared a success or a failure, the weeks in between will likely be filled with debate, speculation and, possibly, high hopes.

Surgeons at London's Moorfields Eye Hospital, led by Robin Ali, a professor, performed the first-of-its-kind procedure Tuesday on Robert Johnson of the United Kingdom, the BBC reported. Johnson was born with Leber's congenital amaurosis, a gene-linked sight disorder that gets worse with age.

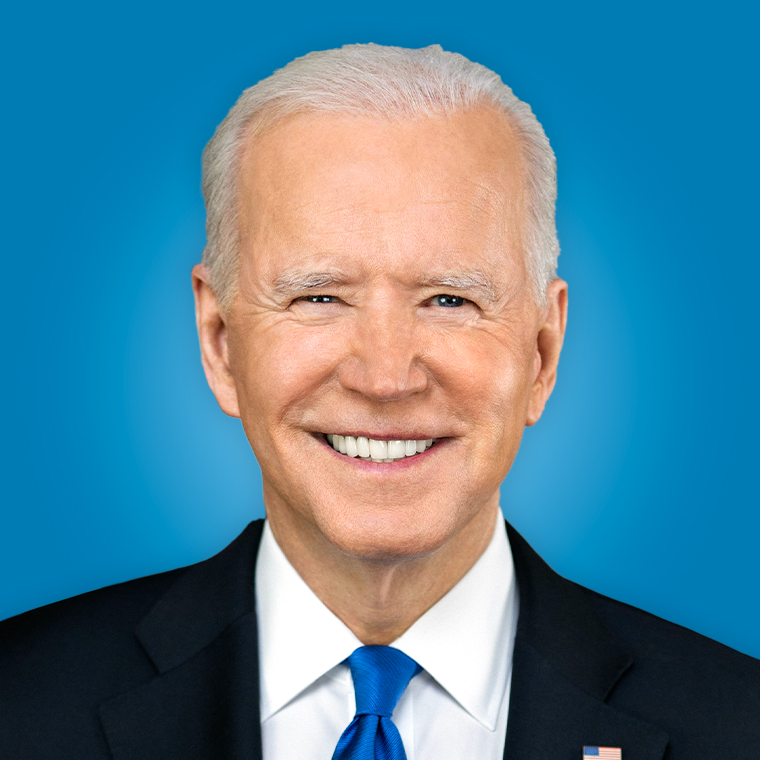

Dr. Paul Sieving, director of the National Eye Institute in Bethesda, Md., says the procedure culminates about 15 years of research and animal experiments. And he is optimistic that the treatment will work.

"A number of years ago they did this with dogs, and five years later, they are still seeing fine," Sieving says. "If it could help people with that condition, it would be wonderful.

"The accumulated hard work of scientists for decades and the genetic revolution of the past 15 years are beginning to pay off."

But Dr. Richard Bensinger, an eye surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, says it is too soon to celebrate, as past gene therapy experiments have shown little progress.

"This logic so far has failed, and no gene transfer experiment has worked," he says.

Whether it succeeds or not, few can argue that the idea behind the procedure is an elegant one.

The reason for Johnson's blindness is a faulty gene in the cells of his retina. This nerve-filled spot in the back of the eye acts a bit like the film in a camera, capturing light and sending the picture it receives to the brain.

Doctors believed they may be able to restore Johnson's sight if they can replace the faulty genes in the cells of his retina with properly working copies. They accomplished this feat using a harmless virus to deliver new, nondefective genes directly into the center of retina cells.