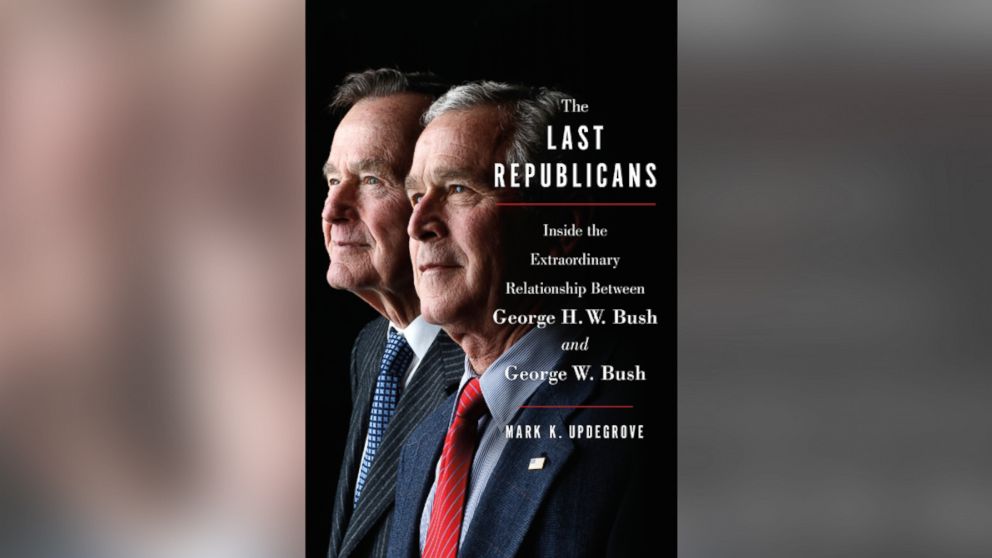

Book excerpt: Mark Updegrove's 'The Last Republicans'

Read an excerpt of "The Last Republicans" by Mark Updegrove.

— -- Excerpted from THE LAST REPUBLICANS: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush by Mark Updegrove by arrangement with Harper, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Copyright © Mark Updegrove 2017

“A FLASH OF LIGHT”

IN THE FALL OF 2012, nearly four years after leaving the White House, six months before the opening of his presidential library, George W. Bush sat in his sleek high-rise Dallas office devoid of pres- idential trappings—no presidential seals or flags, no oil paintings, no Frederic Remington bronzes—and considered his father, the man he had revered since his earliest memories. His sneakered feet and kha- kied legs propped up on a generic executive desk, he leaned back in his black leather chair in a gray golf shirt as he fingered an unlit cigar, looking uncannily like his father at times, particularly when his face turned upright and to the side. The resemblance between the two had deepened through the years, as the younger Bush aged. One could see the old man clearly in his bushy eyebrows, arched and slightly askew, the eyes narrow and squinting at times, and the amorphous opened mouth, though he lacked the patrician refinement in his features; his face was craggier, his hair wirier, and his forehead less expansive. Whatever pressures he had toward his father in his life—to prove himself to him, or surpass him, or rebel against him—had long ago fallen gently away. The stuff about him being the Prodigal Son was “bulls---,” he said in his curt, matter-of-fact Texas twang. Sure, in his late teens and early twenties he had “chased a lot of pussy and drank a lot of whiskey,” but he added, “I was never the Prodigal Son because I never left my family.” He and his dad had gone through some rocky patches—what father-and-son relationship hasn’t?—but his heart was with his father at every step.

Also in the “bulls---” category was media speculation that he and his dad were locked in a competition that intensified during Bush 43’s White House years. George W. never trusted the media, an instinct going back to his days serving his father during the latter’s bid for the presidency in 1988, when he would aggressively demand of reporters seeking interviews, “Why should I talk to you? How do I know you’re not out to get my dad?” The New York Times and the Washington Post! They never let up—and they never got it right. He and his father had always been close, he insisted. Always.

Yet after sixty-six years, much of his father remained a mystery to him. George Herbert Walker Bush wasn’t one to go on about him- self, and despite all they had shared, some things—many things— had gone unsaid, adding to his mystique. “All these questions people assumed my family knew about—my parents had been brought up to be completely reserved and not to talk about those things,” Jeb Bush had observed. And with his life’s shadow growing longer at eighty-eight, the elder Bush had gotten quieter, becoming, in the words of Jean Becker, his longtime chief of staff, “a man of few words.” As George himself put it, “I’ve run out of things to say.”

George’s early adult years in particular were a source of wonder for his oldest son. The latter chapters of his life George W. could better understand because he had gone down similar roads himself: Both found success in business, embarked on ascendant political careers after early losses, and ultimately achieved the pinnacle of power in the White House. But the crowded, storied years of his father’s late teens and twenties were as awesome to him as they were elusive. He marveled at what it was for his father to enlist in the navy on his eighteenth birthday, go to war at nineteen, and become a husband at twenty-one and a father at twenty-two. He could only imagine his father’s excruciating pain after losing his three-year-old daughter, Robin, to leukemia before he was thirty. And he wondered what it was that prompted him to forgo a family pass to the riches of Wall Street after graduating from Yale in 1948 and break away toward adventure and uncertainty in the desolate oil fields of West Texas. Those years were as formative for his father as they were propitious. They shaped him and ushered him early into manhood.

For George W., finding himself and establishing himself in the world would come much later in his own life. It was one of the differences between him and his dad. Indeed, lateness was a hallmark in George W.’s early years, just as it had been when he entered the world on a hot Saturday morning in July, when his father first cast eyes on him.

Barbara Bush, standing five feet eight, had put on sixty pounds awaiting the birth of her first child, who was three weeks past due, as her husband of eighteen months, Yale University freshman George Herbert Walker Bush, pursued his studies. By her own telling, she weighed “more than a Yale linebacker.” During a short summer break, the couple drove from New Haven fifty miles southwest to the Bush family home on Grove Lane in Greenwich, Connecticut, to visit his parents, Prescott and Dorothy—Pres and Dottie as they were known. Sensing Barbara’s great discomfort, Dottie took matters into her own hands. “She put me in the back seat of a car and gave me a little bottle of castor oil to drink,” Barbara recalled. “Then we drove up to New Haven with me moaning and groaning in the back seat as George and his mother said, ‘Don’t worry, everything’s perfectly normal.’”

The party arrived at Grace-New Haven Hospital back in New Haven at half-past midnight, where Barbara gave birth in “a flash of light” just under seven hours later, at 7:26 a.m., on Saturday, July 6. Th fi and most fruitful year of the eighteen-year baby boom, 1946 saw the registered births of 3,288,672 American children. Among them was George Walker Bush.

Barbara and her newborn remained at the hospital for what felt like an interminable eight days after she was told by her doctors that she couldn’t walk up and down the stairs of their one-bedroom apartment on the edge of the Yale campus. “Of course, George couldn’t carry me up the stairs, I outweighed him,” she recalled. “I was thinking I’d never get out again.” Once again, Dottie Bush came to the rescue, inviting her daughter-in-law to join the family at their summer home in Kennebunkport, Maine, where she had hired a nurse to tend to Barbara and her newborn.

George Herbert Walker Bush gave his son three-quarters of his name—minus the Herbert—making it dissimilar enough that he and Barbara would quickly point out that their son was neither a “Junior” nor a George Bush II. It wouldn’t much matter then, nor would it matter later; the George and the Bush were enough. The name came with a paternal yardstick by which he would forever be measured. In his youth, he became known as Georgie or Little George. Translation: Junior.

Wellborn and well-bred in upper-crust New England, the sec- ond of Pres and Dottie’s five children—four sons and a daughter— George Herbert Walker Bush had his own namesake: his maternal grandfather, George Herbert Walker, from whom he also derived the nickname by which he was known from childhood to early adult- hood. George Herbert Walker was lovingly called “Pop” by his four sons—his grandson and namesake became known as “Little Pop” or, more often, “Poppy.”

The four years and one month that had passed between his high school graduation and the birth of George W. had been a virtual life- time for Poppy Bush. The president of his class, he graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, on June 12, 1942, his eighteenth birthday, and began forging his own path the same day. On hand to deliver the school’s convocation on graduation day was Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of war, Henry Stimson, a former Wall Street lawyer and aging emblem of public service who had taken up posts in the cabinets of William Howard Taft, Herbert Hoover, and FDR and would go on to serve Harry Truman. As World War II played out in the European and Pacific theaters six months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the seventy-four-year-old Stimson, a graduate of Andover himself some fifty-eight years earlier, spoke of his hope that the outgoing class would temporarily forgo the war and instead go on to college. The war would be a long one, he maintained, and while America needed men on the front lines, there would be plenty of time for them to serve. What the country needed was leaders, and what they required was the knowledge that a university education would bring.

Pres Bush, on hand with his family for his son’s graduation, listened to Stimson’s sage words hoping that they would strike a chord with Poppy, who had earlier told him of his intention to enlist upon graduation. Soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Poppy was one of many who thought, We had better do something about this, and decided that he would do his part at the earliest opportunity as a navy aviator. Pres had other ideas for his second son. His oldest son, Prescott Jr., had graduated Andover a year earlier and went on to Yale, Pres’s alma mater, where he hoped Poppy, who had already been accepted, would soon follow.

The managing partner of the New York–based Brown Brothers Harriman, the nation’s largest private bank, Prescott Bush was not a man to whom people said no. Poppy would remember him later as “an imposing presence, six feet four, with deep-set gray blue eyes and a resonant voice.” Still, when Pres asked him in a crowded hallway after the ceremony if he had a change of heart upon hearing Stimson’s counsel, Poppy replied, “No, sir, I’m going in.” His father nodded his assent and shook his hand. Afterward, Poppy went to Boston where he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. Later the same day, as Pres drove with the rest of the family from Andover back to their home in Greenwich, he wept. It was the first time his daughter Nancy, two years Poppy’s junior, had seen him cry.

Two months later, on August 6, Pres accompanied Poppy to New York’s Penn Station, where he put him aboard a train that would take him to basic training as a seaman second class in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. There was no certainty as to what lay ahead for Poppy as he left his father’s side, “the youngest guy on the train,” bound, ultimately, for war half a world away. Prescott Bush cried again that day.

The following June, three days short of his nineteenth birthday, Poppy became the youngest pilot in the U.S. Navy when he earned his wings in Corpus Christi, Texas. His father and mother jour- neyed to Texas for the ceremony, where Pres presented his son with a pair of gold cufflinks, which would become his most treasured pos- session, heirlooms he would give to his own son, forty-seven-year-old George W. Bush, over fifty years later before the latter’s inauguration as governor of Texas. From there, Poppy went on to ten months of training to fly torpedo bombers at bases throughout the East Coast, then, in late March 1944, to the South Pacific aboard the USS San Jacinto, where he would see action against the Japanese in his first mission on May 23.

By the summer of the same year, now a lieutenant junior grade, Poppy had seen his share of war. On June 26, after flying his Grum- man Avenger on numerous combat missions, he penned a letter to his parents declaring that the “glory of being a carrier pilot” had “worn off.” Referencing his two younger brothers back home, he wrote, “I hope John and Buck and my own children never have to fight a war. Friends disappearing, lives being extinguished. It’s just not right.” But on the morning of September 2, as Poppy boarded his torpedo bomber with his crewmates radioman John “Del” Delaney and gunner Ted White, war’s iniquities would become far clearer in his mind. And so would its fate.

The three men were charged with a mission to hit a Japanese radio tower on Chichi Jima, a barrier island off Japan’s coast that held enormous strategic significance to the enemy. As their plane approached the tower, it was struck by a hail of antiaircraft fire sending it reeling as Poppy continued the plane’s dive, dropping its payload on the target before retreating impotently back out over the Pacific. Shortly afterward, he shouted orders to Delaney and White to bail out before escaping himself. Minutes later, Poppy found himself alone in the water in a yellow one-man life raft, four miles northeast of Chichi Jima, bleeding, vomiting, stung by a Portuguese man-of-war, and searching in vain for Delaney and White. Using his hands, he feverishly paddled away from Chichi Jima, where the prevailing winds were blowing his raft, to evade certain enemy capture or death. As he did, he thought of “family and survival.”

Throughout his life, luck had a way of finding George Bush. So it was in his most desperate hour. After three hours and thirteen minutes in the water, the USS Finback, a Gato-class U.S. submarine, miraculously peeked up from the water, as five crewmen scrambled to scoop Lieutenant Bush to safety on its deck before the craft dived back under the ocean. Luck was not with Delaney and White, who never rose from the depths of the Pacific.

Bush spent the next four weeks aboard the Finback, and they be- came the most reflective of his young life. Often, as he stood watch on deck from midnight to 4:00 a.m., when the submarine surfaced out on the Pacific, he felt a calm descend on him as he stared into the distance from the conning tower under a profusion of stars. Those moments of solitude left a deep impression on him that he would recall often in his later years. “As you get older, and try to retrace the steps that made you the person who you are, the signposts to look for are those special times of insight,” he said nearly half a century later. “I remember my days and nights aboard the Finback—maybe the most important of them all. In my view, there’s got to be some kind of destiny and I was being spared for something on earth.”

His destiny would become clearer in time. But one of the things that would shape it came more consciously as Poppy contemplated his future; in the face of death he came to appreciate more fully his family and the values handed to him by his parents. And he realized how much he loved the girl whose name graced the side of his downed airplane, the girl—the woman—with whom he would make his future.