What Athletes Do With Their Medals After the Olympics

— -- The presentation of Olympic medals is one of the more spine-tingling ceremonies in sports. National anthems blare from loudspeakers, flags wave through the crowd and tears fall as medals are draped from athletes' necks.

But what happens to those medals once the athletes step off the podium?

We set out to uncover the path of a handful of Olympic medals, some that are historically significant, others that are obscure. Here's what we found:

Gifts from Louganis

By the time Jeanne White-Ginder appeared with retired Olympic diver Greg Louganis at a children's benefit event in 1995, they had been friends for years.

Louganis had befriended her late son, Ryan White, during his well-publicized battle against AIDS in the 1980s, often visiting him in Indiana or inviting him to big diving events. Louganis was so inspired by White's courage -- he had been bullied and expelled from school after contracting HIV via a blood transfusion -- that he gave the teen four of his medals from events such as the U.S. Championships and Pan American Games.

Five years after Ryan's 1990 death, White-Ginder presented a sculpture of her son to Louganis at the benefit in California. Then the five-time Olympic medalist shocked her.

"He reached in his suit pocket and pulled out his gold medal and put it around my neck," White-Ginder said. "And he said, 'I want you to have this. Ryan just meant everything to me and saved my life.'"

The medal was from Louganis' victory in the 3-meter springboard at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Before those Games, Louganis had received the diagnosis that he was HIV positive, but he kept it a secret. On one of his preliminary dives, Louganis hit his head on the springboard and came out of the pool with a bleeding gash. He recovered to win but was shaken. Years later, he recalled that his young friend helped him in that moment. "What would Ryan do in this situation?" he remembered thinking. "I knew he would fight and hang in there. He was my strength."

White-Ginder kept the medal in a scrapbook for years, but thought it was "wasted" and needed to be seen. For a while it was on loan to the International Swimming Hall of Fame in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Today, it's at The Children's Museum in Indianapolis, part of a display of Ryan's bedroom in an exhibit called The Power of Children.

That gold is one of five Olympic medals Louganis won. He earned a silver at Montreal in 1976, and then won four golds by sweeping the 3-meter springboard and 10-meter platform events in 1984 and '88. Louganis gave the gold from the 1984 platform event to Ron O'Brien, his coach.

"He was overwhelmed," Louganis said. "He said he has never heard of an Olympian giving their coach a gold medal."

Though White-Ginder has offered to give Louganis back his medal several times, he has said no. He still has three medals and is happy two went to people who treasure them.

"The medals meant so much to Jeanne and Ron, and I was happy to share them," he said. "As far as I am concerned, the records are in the record books, and they mean so much to them, and I can honor them and their support of me."

-- Doug Williams

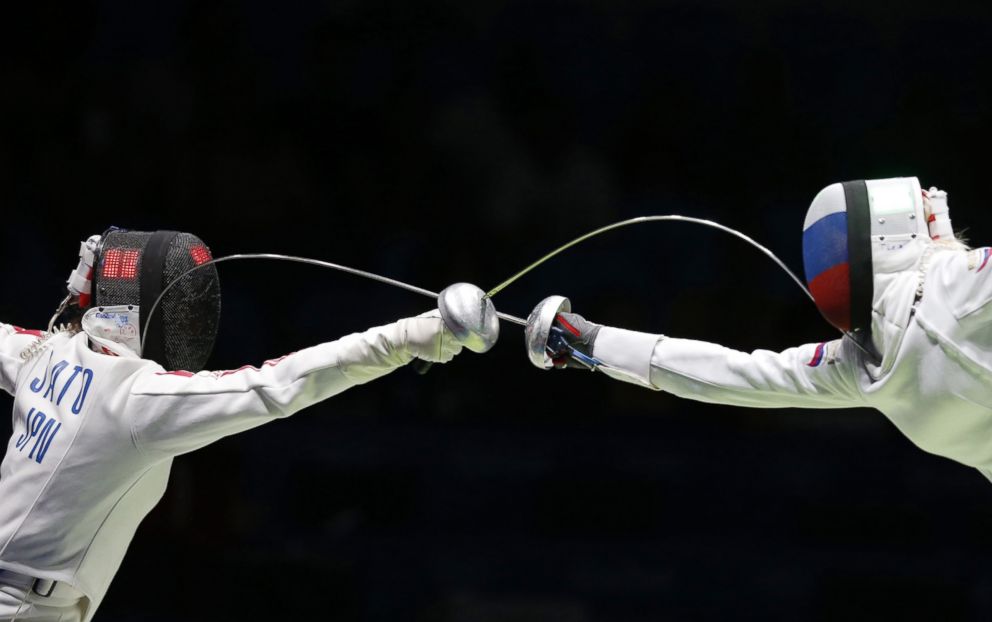

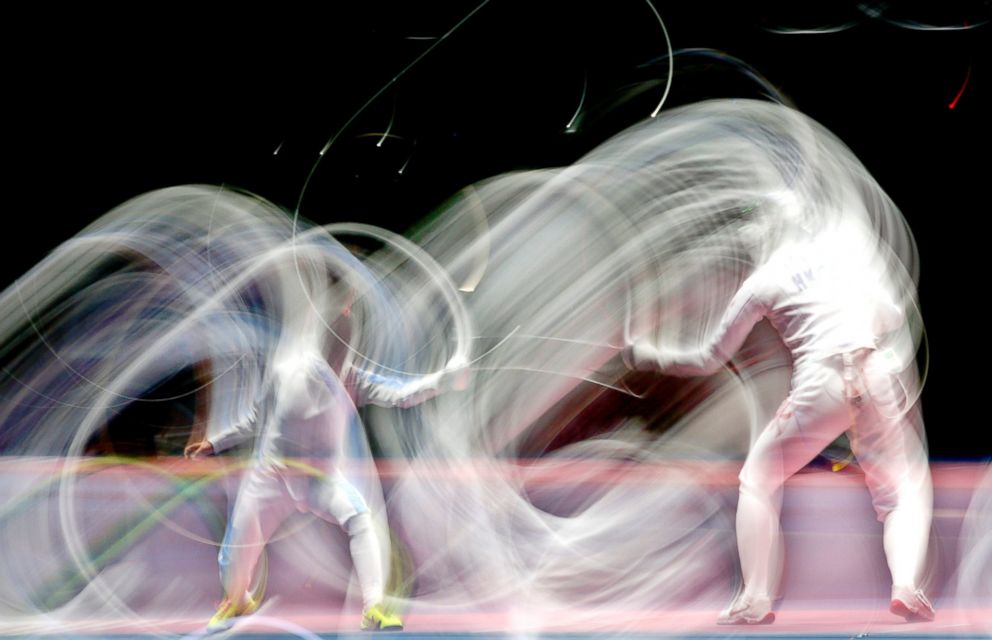

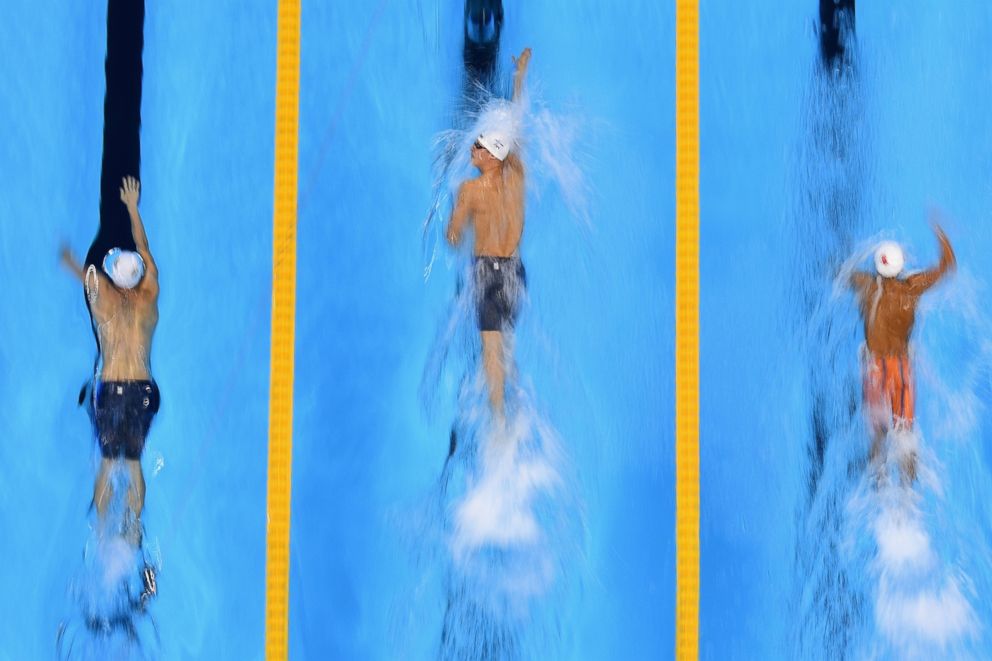

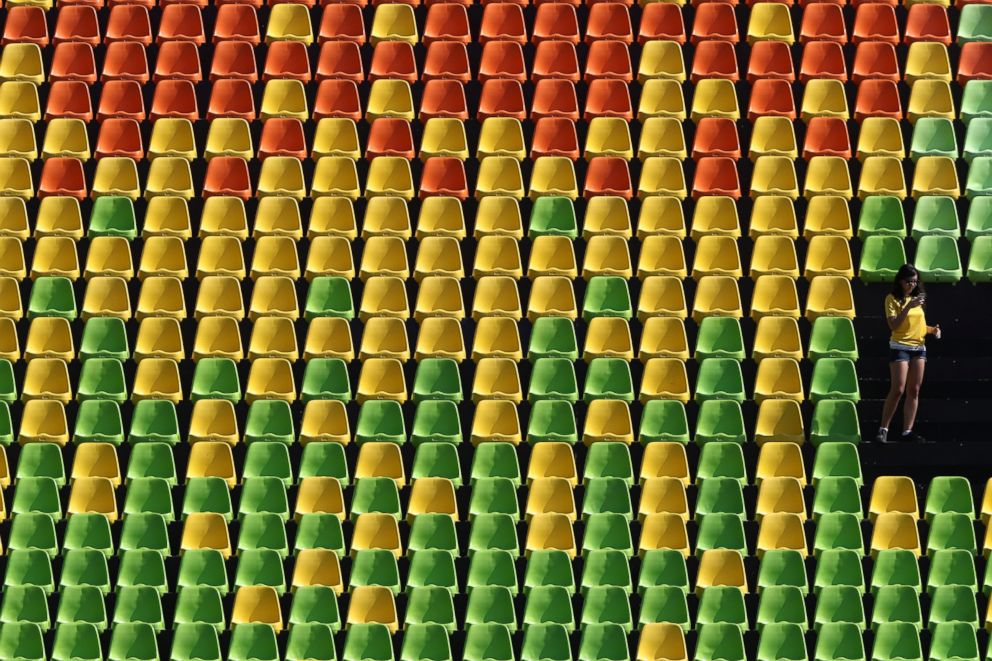

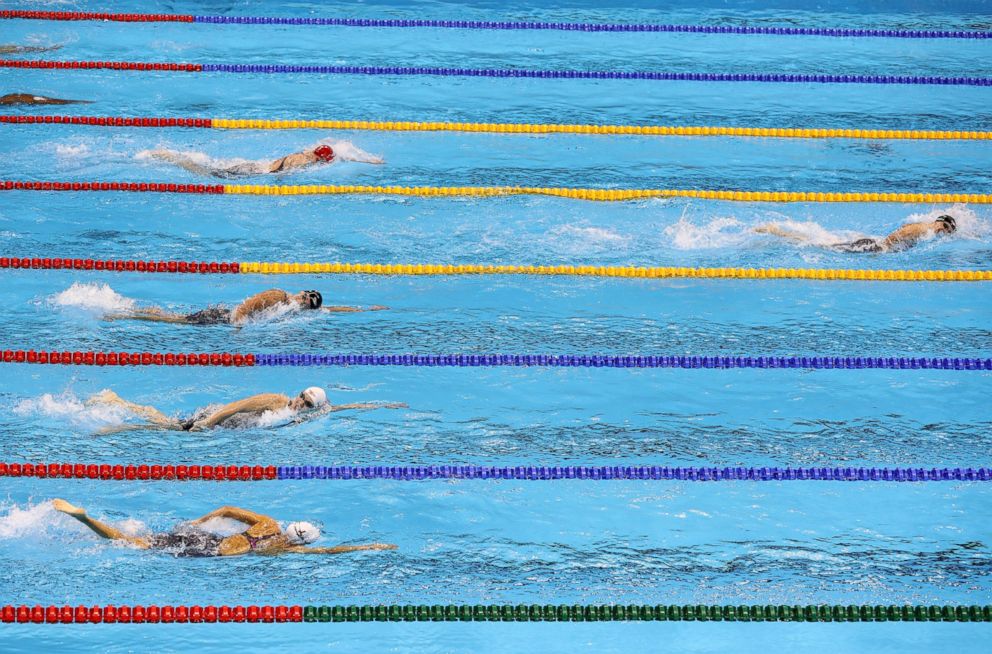

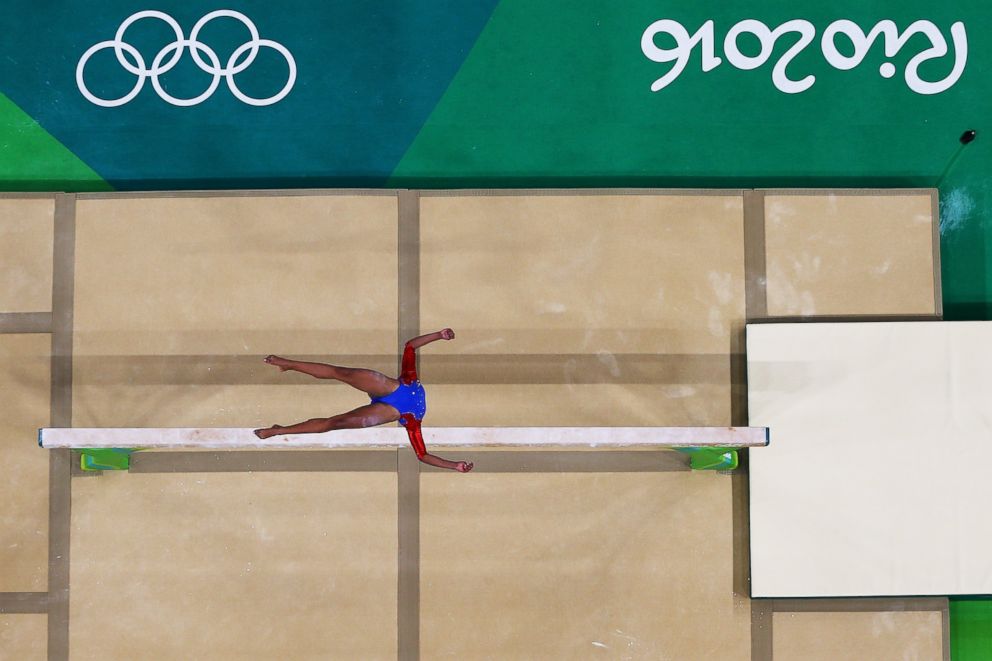

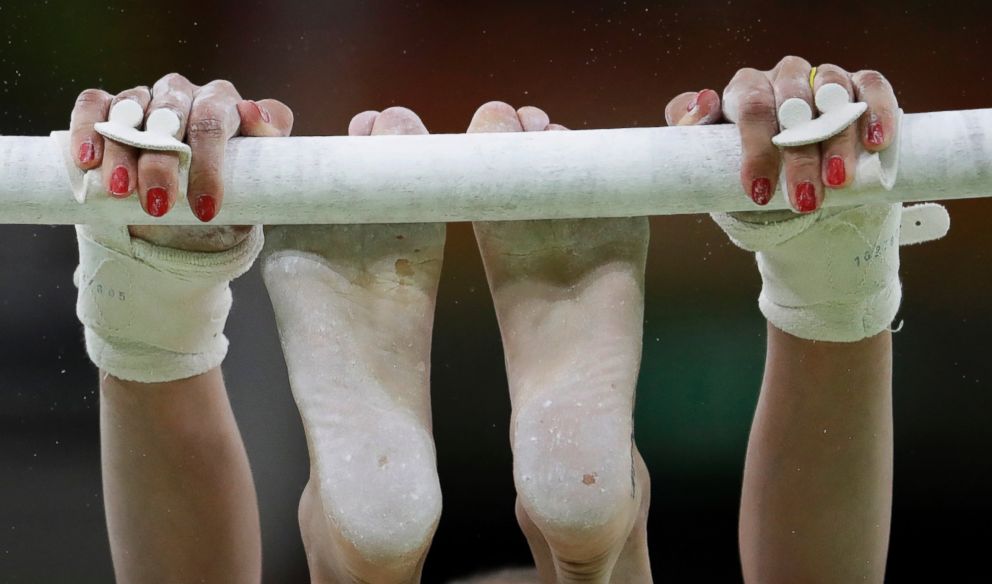

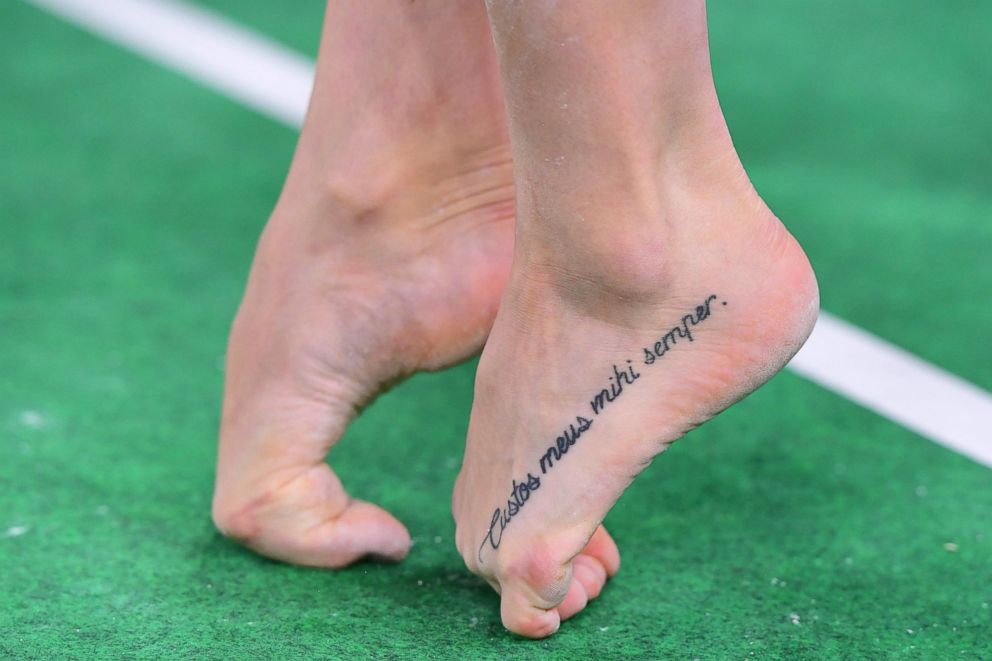

Rio Olympics 2016: Best Photos From Day 1

Smith's famous medal 'under lock and key'

For now, anyone who wants to see Tommie Smith's Olympic gold medal will have to be satisfied with gawking at the replica on his larger-than-life statue at San Jose State University.

The real one is in a vault somewhere in Texas.

"The reason it's there is because that's where I was born, and that's where I want the medal to be," said Smith, who lives in Georgia. "It's under lock and key. ... The medal is still alive and kicking."

The medal means a lot to Smith, 72, who earned it by winning the 200 meters at the Olympics in Mexico City in 1968. He says it represents the years of hard work. But he knows his medal carries a little more cultural (and financial) value than most. It's a piece of 20th century history. That's why it's locked away.

Smith and bronze medalist John Carlos -- his teammate at San Jose State -- famously bowed their heads and raised their black-gloved fists on the medal stand during the national anthem, hoping to call attention to racial inequality. In turn, they stepped into a political firestorm in a turbulent time.

"I wanted to make my feelings known about the racist tendencies not only in America," Smith said, "but the inhuman rights of the rest of the planet. ... The attitude of those who always view others less than themselves."

In the years after 1968, he kept the medal with family in California, while he played wide receiver with the Cincinnati Bengals and taught and coached at Oberlin College. Eventually, he secured it in Texas.

Over the years, he has taken it out to show friends and family, and he'll visit it sometimes on homecomings.

In 2010, he put it up for auction, along with the spikes he wore, to raise money for his program that uses track to help inner-city kids succeed in school. But when bids didn't meet his expectations, he kept the items.

"I couldn't do it for the price they wanted to give me for the medal, because it did represent something," he said.

The glove he wore is long lost. It was part of a pair that he brought home from the Olympics and wore that fall and winter.

"It was cold in San Jose," he said, laughing. "I left them in my car; I'm pretty sure about that. I had a 6-month-old son, and he probably chewed them up."

-- Doug Williams

Rio Olympics 2016: Best Photos From Day 2

Housecleaning uncovers 1904 golf medals

John Ours figured he'd just spend a day this past fall helping his stepfather clean out the house of his mother, who had died at age 101, three years earlier. After other relatives had taken what they wanted from her suburban Cleveland home, all that appeared left were a trove of books, old bills and rustic furniture.

Little did Ours know he would stumble across one of the biggest stashes of golf memorabilia in the sport's history, most notably a gold and silver medal from the 1904 Games, the last time golf was an Olympic event before Rio. The medals were won by H. Chandler Egan and eventually passed down to his only child, Eleanor Egan Everett, who had lived in the Chagrin Falls, Ohio, home for more than seven decades until her death in June 2012.

It was a black metallic box stuffed in the bottom of a book-filled cabinet, blocked by an old rocking chair in a cramped den, that caught Ours' eye. He pulled out the box and could tell by its weight that something interesting was inside.

He sat down with his stepfather, Morris Everett Jr., at the kitchen table, and they popped the lid. On top were various medals Egan, Everett's grandfather, had won in collegiate and amateur events. When he reached the bottom of the box, Everett pulled out a shiny silver medal.

It was the medal Egan had won as runner-up at the 1904 Olympic golf tournament in St. Louis, and it was in surprisingly pristine shape. Along with that memento was the gold Egan won in the team competition.

"We knew the history here, that there were medals, but over the years nobody knew what happened to them," Ours said. "We didn't even have a thought that these things would have been in the house."

Today, those medals are on display at the World Golf Hall of Fame in St. Augustine, Florida, after making their rounds earlier this year at the USGA Museum in Far Hills, New Jersey, and the U.S. Open at Oakmont Country Club outside Pittsburgh.

Everett said he'd like to find a permanent site to display the medals.

"I have a responsibility to my family members, but I can't imagine putting them away for another 50 years," he said.

-- Dan Arritt

Diver takes gold to Rio

The absolute best and most fortunate athletes will take home gold, silver and bronze medals from these Olympics, but U.S. diver David Boudia actually brought the gold medal he won at the 2012 London Games with him to Rio.

Boudia did so because the U.S. divers had a very recent pre-Olympic camp in Atlanta, where he knew they would be visiting a children's hospital. He wanted to brighten up the patients' day by not only showing them his gold medal and letting them touch it, but by placing it around their necks -- as if they were Olympic champions on the podium.

"I know these kids are going through so much, and their parents are also going through so much, that if we can lighten up their day a little bit, at the end of the day, we should do that," Boudia said. "I think they were dumbfounded at how awesome this is, that this is an actual gold medal."

Because he didn't return home before flying to Rio, Boudia brought the medal with him. Not that he is revealing where he's keeping it. "It's in the athletes village somewhere," he said with a smile. "It's a secret."

When Boudia is at home, he keeps the medal in a safe, though he often takes it out for public appearances. And while he keeps the medal in a safe, that doesn't mean he worries too much about it getting stolen.

"If it does get stolen, then it's a medal. We can maybe find a replacement," he said. "If I lost it, it would not be that great. But I would still have my daughter and my wife."

Or, he could always win another one.

-- Jim Caple

Bird's 'cool props'

After basketball star Sue Bird won her first gold at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, she was flying back to Seattle to resume the WNBA season when a flight attendant recognized her and asked to see her medal.

"And before I knew it, that medal was in the cockpit and then in the back of the plane and everyone had seen and touched it," Bird said. "That's when I truly understood what the medal meant. You know what it means, you see it, you experience it, but it wasn't until something like that happened when I truly realized, 'OK, this is pretty big.'"

That medal was just the first of three golds Bird has won in the Olympics, and she could add a fourth in Rio. Among other places, she has kept them in her underwear drawer -- "probably stupid" -- and hidden them inside many things in her mother's house, but she now keeps them in a safety deposit box at a bank.

Bird says that as important as the medals are, they are in some way just "cool props for other people" -- such as the friend who visited her home and wore all three golds while washing the dishes and vacuuming the floor. But it is winning in the Olympics that means much more than the medals you receive as a reward for doing so.

"The medal represents the Olympics," Bird said, "but the whole experience is what resonates, not the actual medal itself."

-- Jim Caple

Basketball medals on the block

Cashing in on Olympic gold has so far proved to be a volatile proposition for several ex-NBA players.

In the past four years, Walter Davis, Jerry Lucas and Vin Baker have dusted off their gold medals -- each won over a decade apart with USA men's basketball -- and placed them up for auction with varying degrees of success.

Davis, a six-time All-Star who remains the all-time leading scorer for the Phoenix Suns, decided to put his 1976 gold medal on the auction block in September 2012. After he set a minimum price of $10,000, it sold for $108,000.

A year later, Lucas asked the same auction house to list his 1960 gold medal, only the former seven-time All-Star had a different idea of what his gold was worth. Lucas, the only NBA champion and Basketball Hall of Fame member among the three, asked for a reserve price of $250,000, but that number was never offered and the medal went unsold.

Baker was a four-time All-Star before his career and personal life took a tumble. Financial woes two years ago led to him auction off his medal from the 2000 Games, the first gold sold that was won by a player in the Dream Team era. He kept his reserve price at $35,000, and it fetched $67,643.

That wasn't the first Dream Team medal to end up on the auction block, however.

Carmelo Anthony parted ways with the bronze he won at the 2004 Games. Anthony was reportedly displeased with his team's performance in Athens and gave the medal to a family member, who auctioned it for $14,080 in July 2014.

Anthony eventually brought home the type of medal he was seeking, winning golds in 2008 and '12.

-- Dan Arritt