Air Marshals Trained to Handle Deadly Threats

Dec. 8, 2005 — -- It is a long-established principle in American law that our cherished rights of freedom of speech and expression do not include the right to scream "Fire!" in a crowded theater when there isn't any such danger. Serious threats to the public welfare (what might happen in a panicked theater evacuation) require corresponding limits on our freedoms to protect public safety.

For many decades, Americans also have understood that bombs, when mixed with civilian airplanes, are also an unquestionable threat to public safety. This is why we've long been willing to prosecute, fine and sometimes jail people who merely uttered the wrong words in the wrong place. As the exasperated cop in the recent movie "Meet The Family" explains to Ben Stiller's character, "You can't say bomb on an airplane!"

Well, yes, you can, but there will be consequences, and as we saw Wednesday in Miami, they can be deadly.

The upset man who drew the undivided attention of a pair of federal air marshals on an American Airlines flight at Miami's International Airport apparently said he had a bomb in a carry-on bag. In other words, he hurdled himself across the line that divides acceptable public eccentricity from unacceptable public risk. In response, the marshals shepherding the flight did precisely what they were trained to do and sprang into action. While we don't have all the facts as yet, what appears to have happened dovetails exactly with the way air marshals are trained: To contain and safely defuse a threat as rapidly as possible.

How do they do that? Well, loud commands are used. Physical intimidation can be used. But when the actions of a threatening person seem ready to migrate from words to deeds, deadly force may be used.

There is no time to psychoanalyze someone threatening to blow up an airplane, nor is there any safe way to trust that an apparently alarmed woman racing up the aisle after a suspect and trying to restrain the marshals isn't an accomplice. The truth is, the marshals, the crew and all of us must understand that the possibility of a bomb must be considered exactly equal to knowing for certain there is a bomb. Thus someone defying clear, shouted orders and reaching for the unseen confines of a bag where an electronic trigger could be hidden has to be considered ready to kill a planeful of human beings.

The federal air marshals have been well trained in the use of a specific mix of high-speed judgment and decisive action. Part of their honed abilities includes making accurate assessments of any threat, and that includes, of necessity, an unquestioning acceptance of any declarative threat someone might make.

In other words, tell them you have a bomb and it will be considered a fact. When the impending actions of such a person include a clear risk of -- in the case of a bomb threat -- explosion, they are trained to initiate a so-called "muscle memory," a series of instinctive actions designed to end the threat. In this case, the proper response in the case of someone ignoring shouted orders and reaching for what has to be considered a possible trigger is precisely what happened.

What the marshals did by preventing the man from having the opportunity to find a trigger bears no relationship to the hindsight revelation that no bomb existed. While it is appropriate for the air marshal service to conduct its own internal review and learn from all aspects of what happened, it would be thoroughly out-of-bounds for us to tolerate a backwash of second-guessing of the actions that we, as a people, authorized, financed, trained and legitimized in the interests of protecting all of us.

On top of that, if it's someone threatening to blow up an airplane you're riding on, the last thing you'd want is hesitation by marshals worried about the public response if they're wrong.

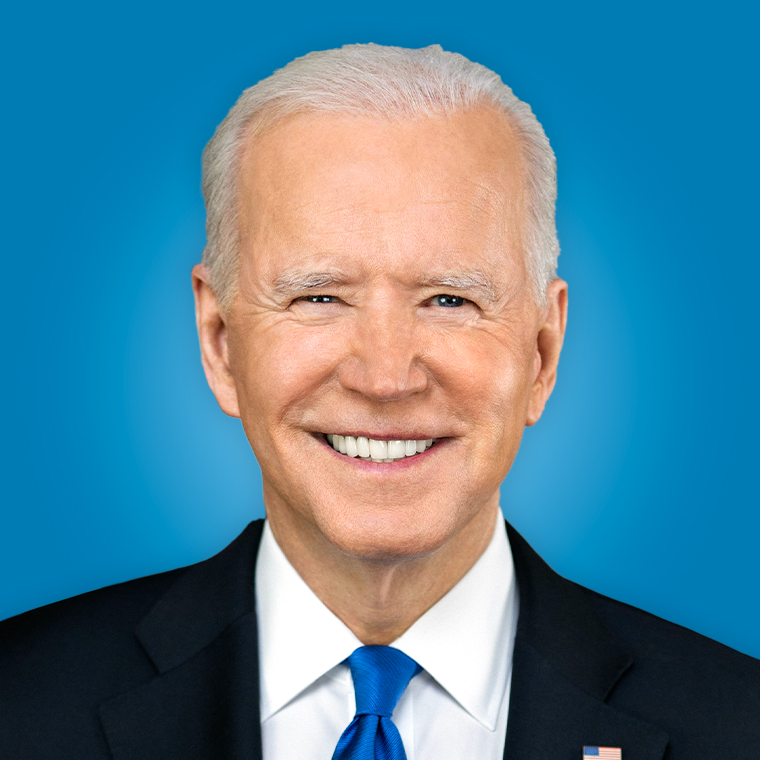

John J. Nance, ABC News' aviation analyst, is a veteran 13,000-flight-hour airline captain, a former U.S. Air Force pilot and a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserves. He is also a New York Times best-selling author of 17 books, a licensed attorney, a professional speaker, and a founding board member of the National Patient Safety Foundation. A native Texan, he now lives in Tacoma, Wash.