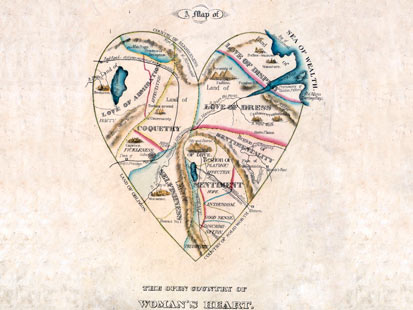

19th Century Map: Women’s Hearts Filled With Selfishness, Affection

A 19 th century map of women’s emotions provides an interesting glimpse inside American conceptions of femininity in the 1800s, thanks to an online exhibit by the American Antiquarian Society.

The piece, titled “The Open Country of Woman’s Heart,” doesn’t exactly paint a rosy portrait of women’s emotions: The largest portions of the lithograph are devoted to less than flattering human sentiments.

“Love of admiration” occupies a large chunk of space, as do “selfishness,” “coquetry,” love of display” and “love of dress.”

Indeed, the artist seems to have viewed women as rather vapid, self-serving creatures, although a large region near the base of the map highlights some positive nurturing qualities: Here, the artist credits women with hope, enthusiasm, good sense, discrimination and prudeness.

Although a note at the bottom of the print reads: “By a lady,” suggesting that the creator was, in fact, a woman, the curators of the American Antiquarian Society aren’t convinced the lithograph was made by a female artist.

“Although the image claims to have been drawn by “a lady,” it is just as likely that it proceeded from the imagination of a man,” reads the description of the piece on the society’s website.

Nancy Finlay, the curator of graphics at the Connecticut Historical Society, said she believes the artist was a woman, although it is impossible to be sure.

“Most popular prints were unsigned,” she said. “So we don’t know if this is really a signature or if it’s just supposed to suggest that this is a woman’s viewpoint.”

This print also has a twin – by the same artist and in the same style – that describes the terrain of the male heart. But while the woman’s heart is “open,” the man’s is “fortified.”

Featured in the male map are the “outer redoubt of dread of matrimony,” “citadel of self love” and the “land of love of money.” As harsh as the artist is toward women, the male is also negatively cast- as a solitary, emotionally stunted, money-grubbing figure.

Both prints were published by D.W. Kellogg & Co., a 19 th century lithography firm based in Hartford, Conn. During this period (around 1835) some lithography firms employed women, though female artists of the 1800s often used male pseudonyms, said Jonathan Cresswell, of Philadelphia Print Shop.

Before the 20 th century a lot of artists didn’t get due credit,” Cresswell said. “There are a lot of women authors that used male pen names, because that was the only way they could get published, and that trend continued into graphic artists.”

For example, female artist Fanny Palmer was one of the most prolific artists at Currier and Ives, D.W. Kellogg’s main competitor.

Susan Casteras, chairwoman and professor of art history at Seattle’s University of Washington, said Victorian representations of gender may seem far-fetched, but they have echoes in 21st century American life.

“We may laugh at Victorians, but we have our own far-fetched interpretations,” Casteras said. “This illustration is one that takes [gendered interpretations] into another realm entirely and points out how ridiculous they seem. Perhaps it’s satirical, but maybe on negative side it’s just damning.”