1 Family, 5 Heart Transplants

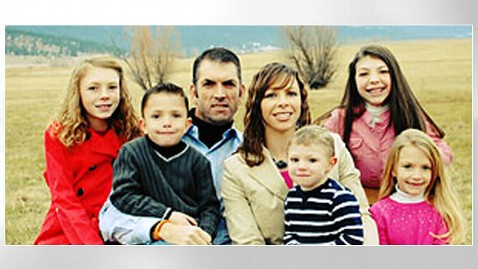

(Stacy and Jason Bingham)

Stacy and Jason Bingham of Haines, Ore., already endured the arduous transplant waiting list until their oldest daughter, Sierra, now 12, found a match for a new heart.

Now, they may have four more rounds on the list to undergo. All five of their children have been diagnosed with genetic heart abnormalities.

For now, only one of the children, who is being cared for at Lucille Packard Children's Hospital in Palo Alto, Calif., has been placed on the transplant list. But if all five of the children receive new hearts, it will be the most heart transplants ever performed for a single family.

More than 3,000 adults and children are waiting for a heart transplant, a minority of whom are children, according to the Organ Donation and Procurement Network. An estimated 400 children undergo heart transplants each year.

Longer survival on the waiting list and a better prognosis post-transplant are some reasons why many children like the Binghams can expect to be treated successfully, according to Dr. Francis Fynn-Thompson, surgical director of the heart transplant program at Boston Children's Hospital, who is not affiliated in the family's care.

"Compared to a decade ago, we have options to bridge between heart transplants," said Fynn-Thompson. "If a child's heart gives out, we can put them on a device that can act like a heart in the interim."

Children waiting for a heart transplant face the highest risk of dying compared to a child waiting for any other organ, according to study Fynn-Thompson and his colleagues published in 2009 in Circulation.

"The smallest hearts are the hardest to find," said Fynn-Thompson.

For child recipients, the ordeal doesn't end once the new organ has been located and transplanted. The surgery is followed by a lifetime of immunosuppressive medications to counter any possible side effects, including organ rejection.

Unlike adult organ transplants, a child-size organ needs to be able to grow as the patient grows. The child eventually transitions from a pediatric to an adult heart transplant cardiologist.

However, unlike an adult, many infants can be transplanted across blood types because they haven't developed the antibodies, allowing for most infants to be transplanted without having to wait for a match.

The prognosis for heart transplant recipients are among the best compared to previous years. The six-month heart transplant survival rate increased from 86 percent in 1999 to 91 percent in 2009, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and the Organ Donation and Procurement Network annual data report.

"Our expectation is that their survival will be well beyond 10 years," said Fynn-Thompson.

Seventy percent of children with heart transplants are alive after 10 years and 50 percent are alive after 15 years, he said.

While pediatric heart transplants are limited by an uncontrollably small donor pool, Fynn-Thompson said the focus should be on helping children who are on the list live longer while they wait.

"Devices like the Berlin heart and other assisting devices coming down the pike are applicable to children," said Fynn-Thompson.

It's these methods that can help one child, even five in one family, live long enough before given the heart they need, he said.