Supreme Court Strikes Down Rigid IQ Cutoff to Execute Mentally Disabled

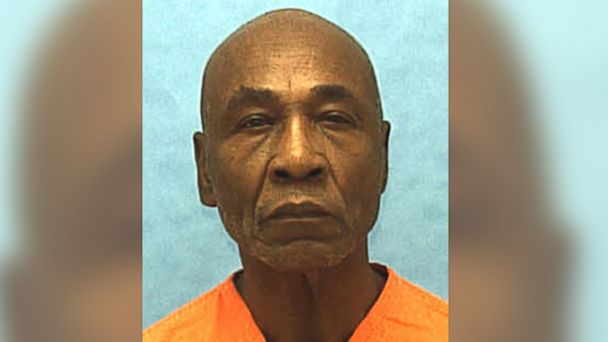

This undated photo made available by the Florida Department of Corrections shows inmate Freddie Lee Hall. (Florida Department of Corrections, HO/AP Photo)

Twelve years after the Supreme Court ruled that the mentally retarded cannot be put to death, today the court clarified the standards a state can use to develop appropriate ways to enforce the ruling.

In a 5-4 ruling, the court said that Florida's threshold requirement requiring an inmate to show an IQ test score of 70 or below before being permitted to present any additional intellectual disability evidence is unconstitutional.

Florida, along with a few other states, sets the IQ score of 70 as a rigid cut off and does not take into consideration a standard error measurement.

Writing for a 5-4 majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy said, "Florida's law contravenes our Nation's commitment to dignity and its duty to teach human decency as the mark of a civilized world. The States are laboratories for experimentation, but those experiments may not deny the basic dignity the Constitution protects."

Kennedy was joined in his opinion by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan.

Kennedy said that when a defendant's IQ test score falls within the test's "acknowledged and inherent margin of error" the defendant must be able to present additional evidence of intellectual disability, including testimony regarding real-world skills and abilities .

"Intellectual disability is a condition, not a number," Kennedy said.

By failing to take into a account a standard error measurement and setting a strict cutoff at 70, Florida "goes against the unanimous professional consensus," he said, noting "that an individual with an IQ test score between 70 and 75 or lower may show intellectual disability by presenting additional evidence regarding difficulties in adaptive functioning."

Florida "is one of just a few States to have this rigid rule," Kennedy noted.

Kennedy stressed that the IQ test is imprecise, but not unhelpful. "A state must afford these test scores the same studied skepticism that those who design and use the tests do, and understand that an IQ test score represents a range rather than a fixed number."

In his opinion today, Kennedy chose to use the term "intellectual disability" - long used by clinicians and practitioners - rather than "mental retardation," the term used in the 2002 landmark case Atkins vs. Virginia, the case that the Supreme Court revisited for today's ruling. Daryl Atkins was convicted of murder for August the 1996 shooting death of airman Eric Nesbitt after robbing Nesbitt. Daryl was later found to have and IQ of 59.

Justice Samuel Alito dissented in today's case, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas.

Alito criticized the majority for relying on the "standards of professional associations, which at best represent the views of a small professional elite."

"In my view," Alito wrote, "Florida has adopted a sensible standard that comports with the longstanding belief that IQ tests are the best measure of intellectual functioning."

He noted that Florida took into consideration multiple test scores and that the majority "never explains why its criticisms of the uncertainty resulting from the use of a single IQ score apply when a defendant consistently scores above 70 on multiple tests."

The ruling was a victory for Freddie Lee Hall, who is on death row for the 1978 murder of Karol Hurst, a pregnant 21-year-old newlywed. Hall's lawyers claimed that his family recognized his disability when he was a small child and his teachers repeatedly classified him as mentally retarded. Hall asked a Florida state court to vacate his sentence presenting evidence that he had an IQ test score of 71.

Seth Waxman, a lawyer for Hall, had argued "Florida's clinically arbitrary bright-line rule under which a person with an IQ test score of 71 may be executed notwithstanding a consistent diagnoses of mental retardation flouts the constitutional principles this Court recognized in Atkins. "

Waxman wrote in briefs that IQ test scores are not "perfect measures of a person's intellectual ability" and that a person who obtains a test score between 70 and 75 "may be diagnosed with mental retardation, depending on the other clinical evidence supporting the diagnosis."

Florida's Attorney General had defended Florida's protocol and said that Hall was simply seeking to avoid execution.

In court papers, Attorney General Pamela Jo Bondi wrote, "this case turns on whether Atkins truly left any determination to the States or whether, as Hall contends, States are constitutionally bound to vague, constantly evolving - and sometimes contradictory - diagnostic criteria established by organizations committed to expanding Atkins' reach. "