A Look Back at Presidential Responses to Racial Violence

A protester takes shelter from smoke billowing around him, Aug. 13, 2014, in Ferguson, Mo.

ABC News' Elizabeth McLaughlin and Jake Lefferman report:

At the height of the racial turmoil in Ferguson, Missouri, President Obama interrupted his Martha Vineyard vacation to urge calm and promised an open investigation into the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager shot and killed by a police officer.

Tear Gas vs. Molotov Cocktails in Ferguson Protests

Michael Brown's Parents: "Stop the Violence"

Since the shooting, five days of protest have rocked the St. Louis suburb, where police have unleashed tear gas and smoke bombs to try to control the angry mob.

ABC News takes a look back at race riots across America and how presidents have responded throughout history.

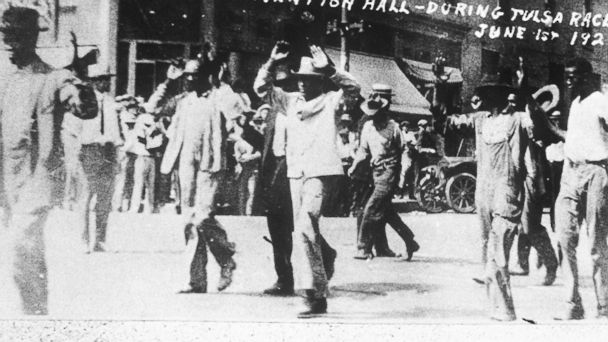

Black detainees are led to the Convention Hall following a race riot in Tulsa, Okla, June 1, 1921.

Tulsa, May and June 1921

Post-WWI Oklahoma erupted in a deadly race riot in 1921 in the prosperous Greenwood District, a mostly African American neighborhood of Tulsa. Left out of history books for decades, the 18-hour violent clash left between 50 and 300 dead and over 1,000 homes and businesses destroyed, according to the historical society.

By the time the National Guard arrived the morning after the riot, 35 city blocks had been burned to the ground and countless were injured.

President Harding discussed the riot while addressing students at Lincoln University. The president was "shocked" and expressed hope that "such a spectacle would never again be witnessed in this country," according to a New York Times article from June 7, 1921.

A mob upsets a car as police stand nearby powerless to intervene as race rioting spread to many parts of Detroit, June 21, 1943.

Detroit, June 1943

Riots between blacks and whites at the Belle Isle integrated amusement park led to three days of violence beginning on June 20, 1943. Thirty-four people lost their lives. Of the25 blacks who perished, 17 were killed by white police officers. President Roosevelt released a " proclamation" on June 21, saying,

"Now, Therefore, I, Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, do hereby make proclamation and I do hereby command all persons engaged in said unlawful and insurrectionary proceedings to disperse and retire peacefully to their respective abodes immediately, and hereafter abandon said combinations and submit themselves to the laws and constituted authorities of said State;

And I invoke the aid and cooperation of all good citizens thereof to uphold the laws and preserve the public peace."

Clashes between African Americans and police officers in Rochester, New York, began with incidents like this where police aimed fire hoses at residents, July 27, 1964.

New York City, July 1964

On July 18, 1964 in Harlem, a white police officer shot and killed James Brown, a 15-year-old African American. His death inspired thousands of residents to riot in New York City neighborhoods for six days. On July 21, President Lyndon Johnson addressed the nation, saying,

"It must be made clear once and for all that violence and lawlessness cannot, must not, and will not be tolerated. In this determination, New York officials shall have all of the help that we can give them. And this includes help in correcting the evil social conditions that breed despair and disorder.

American citizens have a right to protection of life and limb-whether driving along a highway in Georgia, a road in Mississippi, or a street in New York City.

I believe that the overwhelming majority of Americans will join in preserving law and order and reject resolutely those who espouse violence no matter what the cause.

Evils acts of the past are never rectified by evil acts of the present. We must put aside the quarrels and the hatreds of bygone days; resolutely reject bigotry and vengeance; and proceed to work together toward our national goals."

Smoke rises from a shopping center burned by rioters, April 30, 1992, as the Los Angeles skyline is partially obscured by smoke.

Los Angeles, April 1992

On April 29, 1992, officers charged with brutally beating Rodney King were deemed "not guilty" by a jury of 10 whites and no African Americans. For three days, violence erupted across Los Angeles, prompting President Bush to send military troops and riot-trained law enforcement to the city. On May 1, the president spoke about the "civil disturbances," saying,

"Television has become a medium that often brings us together. But its vivid display of Rodney King's beating shocked us. The America it has shown us on our screens these last 48 hours has appalled us. None of this is what we wish to think of as American. It's as if we were looking in a mirror that distorted our better selves and turned us ugly. We cannot let that happen. We cannot do that to ourselves…

Tonight, I ask all Americans to lend their hearts, their voices, and their prayers to the healing of hatred. As President, I took an oath to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution, an oath that requires every President to establish justice and ensure domestic tranquility. That duty is foremost in my mind tonight."

ABC News' Erin Dooley contributed to this report