Here’s Why Public Colleges Give Their Money to the Rich Kids

Schools practice something called ‘financial aid leveraging’

Sept. 11, 2013— -- Public colleges that have traditionally offered low-income students access to affordable education now give an increasing percentage of their financial aid to wealthy students instead.

According to a recent analysis by ProPublica and the Chronicle of Higher Education, schools use what people in the industry call “financial aid leveraging” to give discounts to top-performing or wealthy students over poor kids.

Why?

As states have tightened education budgets, public universities have had to contend with limited resources. They also continue to face pressure to improve their rankings in lists like U.S. News & World Report’s. SAT scores matter when it comes to those rankings, and schools want to attract a cohort of students who test well.

Studies have indicated that there’s some correlation between income and test scores, and the upshot is that kids from wealthier backgrounds generally test better. So schools take what scholarship money they have and divide it into “incentives” for wealthier, high-scoring students who don’t necessarily need them.

Here’s an illustrative hypothetical:

Susie scored a 1500 on her SAT and comes from a family that can afford to pay her tuition at the two universities she’s considering attending. School A is really looking to raise its ranking and knows having Susie’s good score will help. So it ponies up a small “we really want you” scholarship. Susie feels special, and she chooses School A over School B. Aside from the small scholarship, Susie’s family pays full tuition and fees.

That scenario plays out over and over. But that doesn’t make it right.

Say another student, Sally, also wants to go to School A. Sally was admitted but can’t begin to afford the tuition. She’s a good student and lands well within the school’s averages, but her test scores are also lower than Susie’s. So while the school has said she’s welcome to attend, she’s not necessarily going to help them raise their ranking or bring in money, and they’ve chosen to use their limited funding to target students like Susie, not her. So Sally has to attend Community College C instead, and hope for a more favorable situation in two years.

There’s a confluence of events leaving people like Sally in the dust. Besides rising tuition costs -- and public colleges have pushed up their prices higher than private schools in recent years -- the recession has hit low-income kids the hardest. So when they also miss out on aid opportunities, they fall even farther behind well-off students.

“Over roughly two decades, four-year state schools have been educating a shrinking portion of the nation’s lowest-income students,” reads the ProPublica/Chronicle of Higher Education piece. “The task of educating low-income students has increasingly fallen to community colleges and for-profit schools.”

The colleges say their aid practices actually attract more money from wealthier students, which they can distribute to low-income kids in the long-run. The schools add that they don’t have access to the same billions in endowments that the nation’s most prestigious private universities hold.

But the practice still leaves poor students scrambling for an education.

“It’s a common phenomenon in higher education,” the analysis points out. “[S]tudents with less money [are] relegated to institutions with less money.”

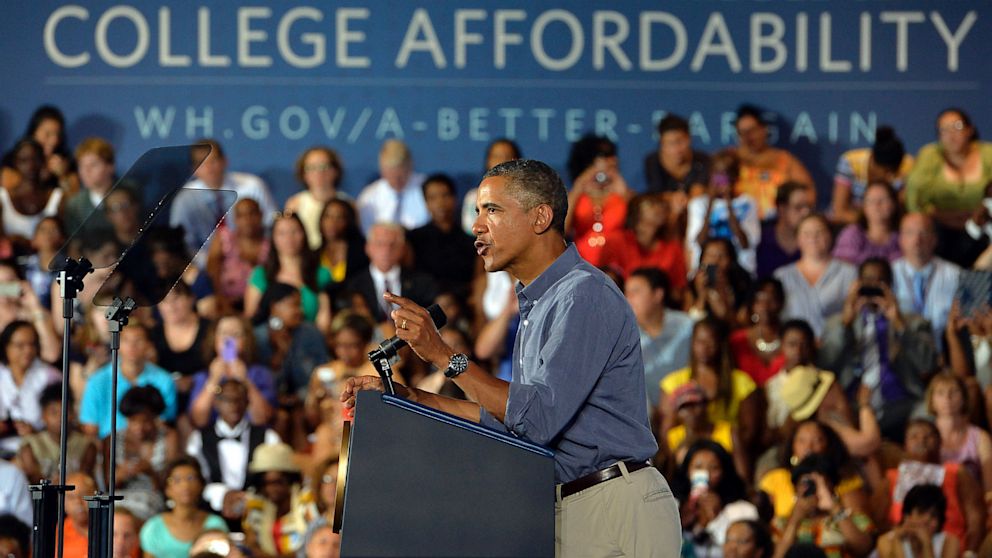

President Barack Obama announced a college affordability plan last month that includes developing a ratings system, which would partly tie the schools’ federal funding to how well they distribute their aid to the neediest students.

Whether that plan comes to fruition remains to be seen. But unless something is done, state schools have little incentive to serve the low-income students who for so long have counted on them as the gateway to a better future.