First Man in US to Get Double Hand Transplant Highlights Risks of Experimental Surgery

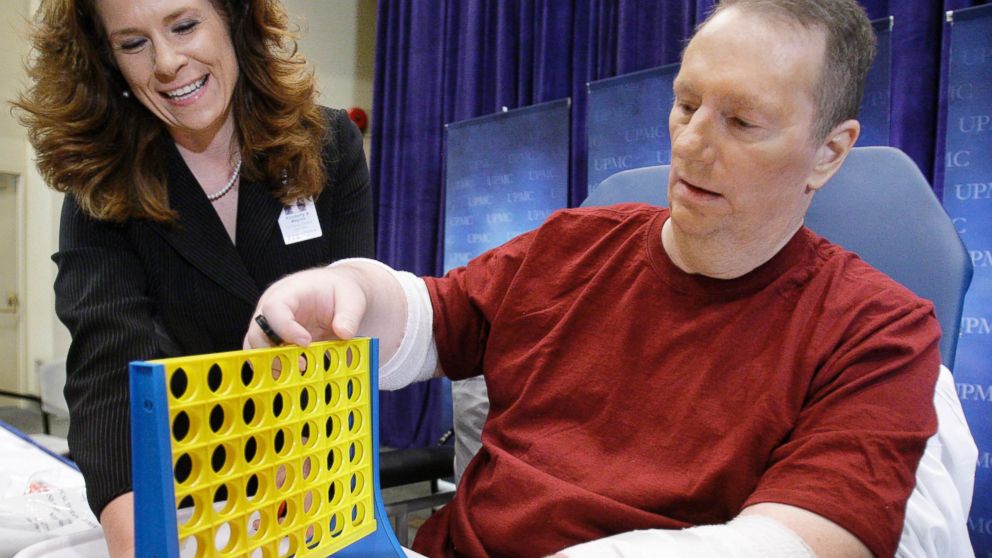

Jeff Kempner cannot move his hands despite a transplant in 2009.

— -- The first American patient to undergo a double hand transplant is speaking out about his experience this week. Seven years after making headlines, Jeff Kepner, 64, is drawing attention to the risks of experimental surgery by revealing he cannot move his transplanted hands at all.

"I have zero mobility with my hands," Kepner, 64, told ABC News. "I can’t hold a pencil."

Before deciding to get the transplant, Kepner, of Augusta, Georgia, spent 10 years as an amputee. Today, he said he's been unable to work because of the trouble with his hands. He said he doesn't want to go through surgery again to remove the hands, since there would a risk that too much tissue would be taken and he wouldn't be able to use prosthetics afterwards.

Kepner's case has highlighted how patients undergoing experimental surgeries can face devastating consequences and risks long after they are hailed as medical marvels. While many patients with hand transplants are able to regain some use of their new hands, others run the risk of having no feeling or losing the transplant organ to immune-system rejection.

Dr. Vijay Gorantla, associated professor of surgery and administrative medical director of the Pittsburgh Reconstructive Transplant Program at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, treated Kepner and said it's key that doctors make sure that patients truly comprehend the myriad of risks behind experimental surgeries.

"Setting expectations for patients is one thing, but making patients understand those expectations is another thing," he told ABC News.

Gorantla explained that in patients where these kinds of tissues are transplanted, the ability for nerves to regrow properly is a huge risk. The nerves must grow before the small muscles that allow for movement wither away after surgery. Gorantla compared it to a broken light bulb.

"You have a wire in the house and it’s connected to a socket and you switch it on but the bulb doesn’t glow because the bulb is dead," he explained. "If you compare the bulb to the muscle it doesn’t matter after some time to have electricity or cable if you lose the muscle."

Gorantla said it's key for patients to do physical therapy to ensure the nerves can get to the muscles again, but that there is always a risk. He pointed out the field of this kind of transplants, including hands, face, abdominal wall and uterus transplants is still new. It began in 1998 with the first face transplant in France.

"As with every procedure in medicine we have known risks and known benefits and known complications," Gorantla said. "There are things we just don’t know because of the novelty of the whole field. The age of the field is 15 or 16 years worth of data and that [data] generates from a few hundred patients."

Gorantla pointed out doctors must be clear about risks for patients and must also avoid "undue risks."

"There are no absolutes here and that’s why you have to face the specter of failure amidst the success," he said.

Kepner said he's frustrated by his lack of mobility and the fact that he feels he is in a worse position than he did before the surgery.

After speaking with doctors about his prognosis, he said, "I really had high hopes I would have feeling my hands."

But Kepner remains an example of the risks both patients and doctors take when heading into uncharted surgeries.

"I was in therapy for almost three years and after the third year I said 'Hey enough is enough,'" he said. "My fingers weren’t moving half an inch they weren’t doing anything."

When asked if he had advice for others considering similar experimental surgery, Kepner said they should consider what is right for them.

"If they want to do this that’s fine. I wouldn’t say anything negative," he said. "They’re getting better."