Parents cheer new treatment for rare disease, though their children won't benefit

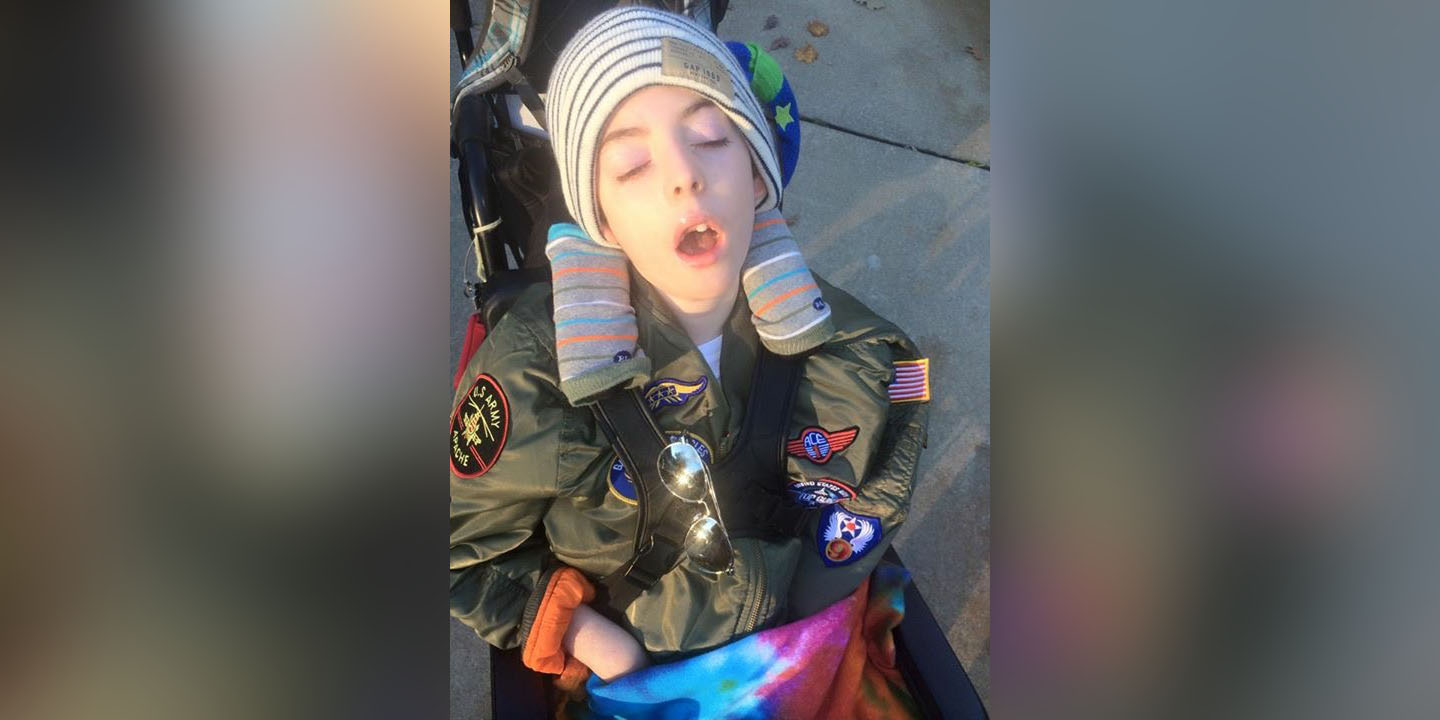

The VanHoutans' son and daughter were diagnosed with Batten disease.

— -- For eight years, Tracy and Jennifer VanHoutan have been working to understand and find a treatment for a rare genetic disorder called Batten disease.

The VanHoutans aren't scientists or doctors with medical degrees or a laboratory; they're parents of children diagnosed with the disease. In 2009 the couple's eldest child, Noah, was diagnosed with Batten disease, a progressive terminal neurological disease that can leave children blind and unable to talk or communicate and with dementia. A year later, their daughter Laine was also diagnosed with Batten.

"[Doctors] said, 'Take your children home and enjoy the time you had left with them,'" Tracy VanHoutan recalled. "That didn't sit well with us and we started looking at different avenues."

The couple founded Noah's Hope and started working with the Batten Disease Support and Research Association to help raise money for research that could hopefully lead to a cure or treatment. They traveled to conferences, met with researchers and agreed to fund research before they had much in the way of donations to offer. Tracy VanHoutan spent years on the BDSRA's board.

"The way we look at it is our house is literally on fire and the kids are inside of it, what are you going to do about it? We're not going sit there and wait," he said.

Last week the Food and Drug Administration approved the first treatment for Batten disease. The therapy, Brineura, treats one type of Batten disease (there are 14 types), late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2). It's not a cure, but the treatment, which replaces enzymes, has been shown to stop or delay the progression of Batten disease.

"Seeing all of that come to fruition in an approved product last Thursday — it was rewarding, and it was bittersweet," Tracy VanHoutan told ABC News.

The VanHoutans' Noah's Hope foundation is one of several family foundations that, together with the BDSRA, helped fund early research into Batten disease and potential treatments, including the enzyme replacement therapy that eventually lead to Brineura, according to Margie Frazier, the executive director of BDSRA.

"It's very important to note that these early funds were raised by parents who were very, very hopeful [while] knowing that their children were not going to benefit," Frazier told ABC News.

Frazier called the treatment a "milestone" for the community, even though it treats only one form of Batten disease.

The VanHoutans celebrated the treatment's approval, despite the fact that it arrived too late for their children.

Noah, who grew up loving soccer, steaks and the Cubs, died last year just a few weeks before his 12th birthday. Their daughter Laine has the same type of Batten disease that is treated by Brineura, but her disease has progressed too far for the treatment to work.

"It was difficult," Jennifer VanHoutan said, but added that knowing so many children will be helped with the treatment "softened" the news.

"Laine had a smile on her face all week," Jennifer VanHoutan said.

The VanHoutans have not given up hope and continue to work to find new avenues for treatment and better testing so that families aren't left wondering what is wrong with their children during a long diagnosis process. Jennifer VanHoutan said it took 16 months for Noah to get diagnosed with Batten disease and said they've met other parents who didn't know until after their child had died from the disease.

"We tried to do everything we could," Tracy VanHoutan told ABC News of their work to save their children. "We may not push quite as hard as we did in those early years ... We're more efficient."