Why We Choke When All Is on the Line

It may be that thinking too much can cause you to choke, researchers say.

Aug. 18, 2013— -- One second left on the clock, and the basketball star who seems to be able to make any shot from anywhere on the court has just been fouled. His team is two points behind, but no worry.

All he has to do is make two free throws, a piece of cake for someone of his talents. The fierce action on the floor freezes as players on both sides take a mandatory breather. There's nothing the defense can do.

The first shot is perfect, nothing but net. The second came straight from hell, rolling around the rim and dropping off to the side. Game over.

It's happened to all of us, although not necessarily on a basketball court. The big moment arrives, and we've done it so many times before that we don't even have to think about it.

But sometimes we do think. And that's the wrong time to do it. We miss that critical shot, or we flubbed an important line, or we forgot the boss' name just as we were supposed to introduce her.

The one time we really needed to pull it off, and we choked. Why? A growing body of evidence shows the answer may be incredibly simple. Thinking too much at the wrong time can be a bad thing because your brain tries to take charge at the precise moment when your body doesn't need any help.

Your muscles, for anything from shooting a basketball to simply breathing, have their own memories. You don't have to tell your heart when to beat. And if the "executive" part of your brain butts in, it's probably going to hurt, not help.

"We call it overthinking," neuroscientist Taraz Lee of the University of California, Santa Barbara, said in a telephone interview. Lee, lead author of a study in the Journal of Neuroscience, said our bodies learn to do some things so well that if we think about what we are doing while under intense pressure it may actually hurt our chances of succeeding.

"The part of the brain [responsible for planning, executive function and working memory] may be telling parts of the brain that control muscles to do something they are not supposed to be doing," said Lee, a former basketball player. "So it can wrestle control from the automatic plan and try to pay attention to the step-by-step control of a free throw or something like that."

In other words, a skilled player's body already knows how to make the shot. Too much info can mess it up.

Psychologist Sian Beilock of the University of Chicago calls it "paralysis by analysis." Beilock, author of the book, "Choke: What the Secrets of the Brain Reveal About Getting It Right When You Have To," contends that too much thinking at the wrong time can lead to "logjams in the brain."

Lee, one of many scientists these days trying to understand why we fail under pressure, is particularly interested in why superstars in sports can choke while trying something that, to them, should be easy.

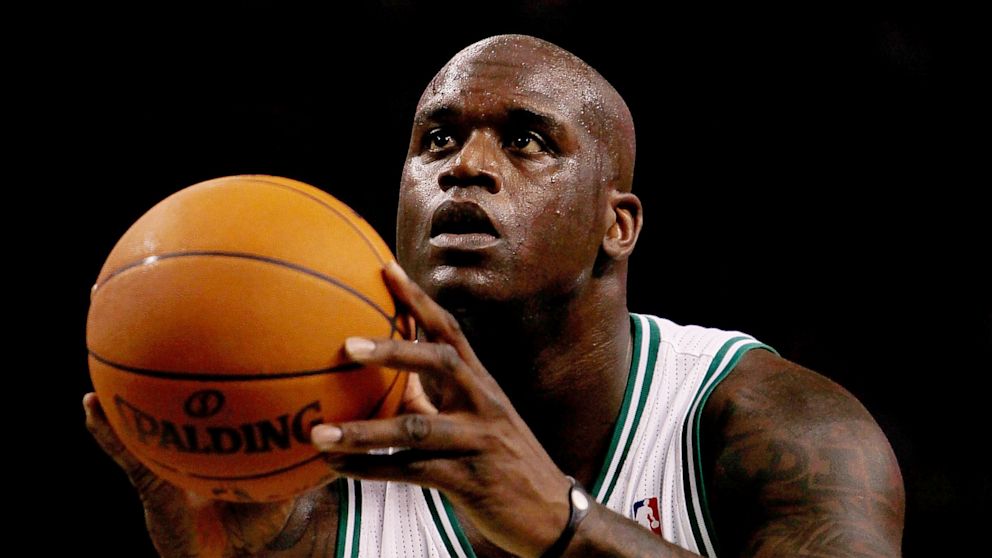

We've seen it over and over. Shaquille O'Neal, who dominated so many games during 19 years in the National Basketball Association, was so notoriously bad at free throws that he became a popular target among defenders.

Why risk getting clobbered by his elbows under the basket if they could send him to the line, where he would more likely fail? (He missed nearly half of his free throws over his career.)

The opponents had a name for it: "Hack-a-Shaq."

Choking under pressure is even more conspicuous in professional golf. It's not uncommon to see a pro drive the ball around 300 yards and then miss a one-foot putt.

Just two years ago, golfer Jason Dufner blew a four-stroke lead with four holes to play, losing the prestigious PGA Championship in a devastating demonstration of choking under pressure.

But this year, he won it.

Researchers generally concentrate on two different explanations for why experts choke.

Chicago's Beilock believes it boils down to two opposing theories: Either the person worries so much even a well-practiced talent can fail, or he or she concentrates so much on the task at hand that the brain overrides the well-trained muscles.

UCSB's Lee, in the first of a series of experiments, is searching for neurological clues about what, exactly, is going on in the brain. He and his colleagues used a valuable new technique, called transcranial magnetic stimulation, to briefly manipulate two areas of the prefrontal cortex -- the relatively young part of the brain often cited as the reason we humans are different from other animals.

The scientists stimulated the part of the prefrontal cortex that performs executive functions -- the "take charge" part of the brain -- to see if that had any effect on the part of the cortex responsible for muscle memory. They found that if they "turned up" activity in the executive region, then activity in the muscle memory area decreased. If they turned down the activity in the executive area, the muscle memory region became more active.

That suggests to the researchers that thinking too much may indeed have a bad impact on our ability to repeat a task that we've mastered over the years, whether it be hitting a golf ball or giving a speech.

The take-charge part of the brain "is exerting its control when it's not really necessary," Lee said.

So what's a body to do?

Chicago's Beilock says it may help to just figure out a way to distract yourself. Maybe instead of thinking so hard about making that free throw, Shaq should have hummed a little tune.

That's right. Just humming a tune might turn disaster into triumph, she contends.