Skulls Tell Story of Social Growth, Scientists Say

The need to work together long ago spawned the age of self expression.

— -- How did our early ancestors discover the wonders of art and music and culture so long ago? They found it, according to new research, because they had finally learned to be nicer to each other.

One critical change in the course of human evolution, according to the study, was a gradual reduction in the potency of testosterone, the bad boy among hormones responsible for aggressiveness and anti-social behavior.

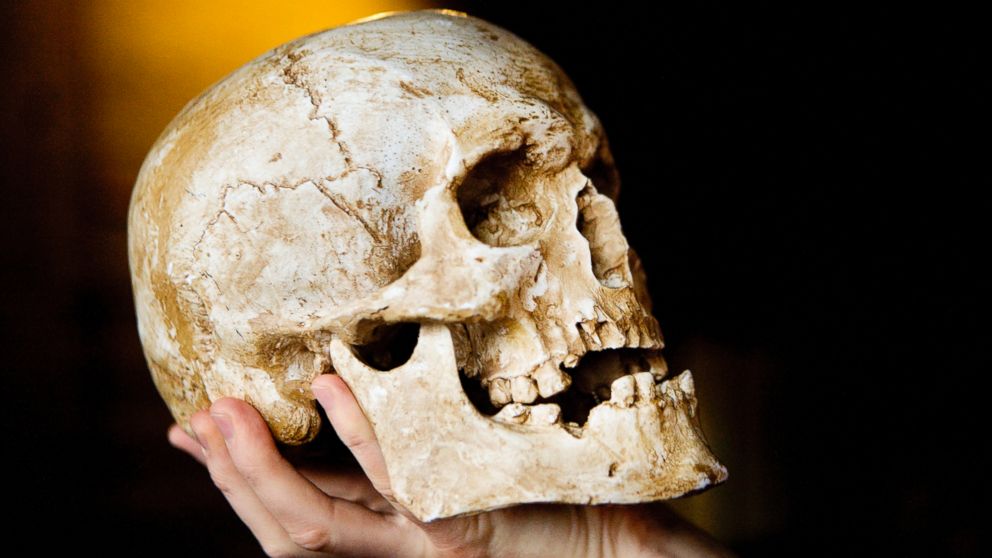

A team of anthropologists at Duke University studied more than 1,400 skulls from the dawn of human history to the present and found evidence that the things we love so much -- art, tools, even jewelry -- resulted from the need to form clans and work together.

Robert Cieri, then a graduate student in biology, began the study three years ago at Duke, by examining 13 human skulls more than 80,000 years old and 41 skulls between 10,000 and 38,000 years old.

He and his colleagues also analyzed 1,367 20th century skulls from 30 ethnic populations in museums around the world. Cieri, now a doctoral candidate at the University of Utah, is the lead author of a paper published in the journal Current Anthropology.

How the Cuckoo Wages an 'Evolutionary Arms Race'

How the Clever Hummingbird Tortures Scientists

How The Naked Mole Rat Could Help You Live Longer

The scientists found physiological changes in the skulls that most likely resulted from hormonal changes over many generations as humans slowly moved away from isolation and into social structures that required more cooperation.

The need to work together gradually reduced the influence of testosterone, which in turn changed the physical structure of the skulls, the study contends.

The human skull became more feminine, with a gentler appearance.

Testosterone, like many hormones, plays a role in the physical development, even in the embryonic stage, both in humans and other mammals.

In humans, it partly determines the lengths of the second to fourth digits. Its effect on the cranium is dramatic, as documented in a famous experiment with Siberian silver foxes. The animals were bred only for tameness, yet the structure of their skulls changed, along with other body traits, over many generations as the foxes learned to trust humans as friends.

The human skulls examined by the Duke scientists also changed over generations as the brow lost its high ridge and the skull became rounder, and more feminine.

Those changes -- not just in appearance but in the influence of testosterone -- also made it possible for humans to build ever more complex societies that were more densely populated, eventually resulting in megacities.

The sequence is this: First the need to work together, less aggression, then cranial changes, then even less aggression as humans moved from individualistic hunter gatherers to farmers and finally to urban dwellers.

All of this is based on the study of skulls, but critics -- including some who are intimately familiar with the research -- point out that much more needs to be done before this idea is accepted in a scientific discipline noted for its wide range of varying opinion.

Indeed, how we became what we are today is one of the most hotly debated topics in science, largely because the evidence itself is problematic. Ancient skulls are dated primarily on the basis of known geological ages of the soils in which they were found, which is also open to different interpretations.