New Kodak Will Sell Nothing to Consumers

The picture of post-bankruptcy Kodak comes into focus.

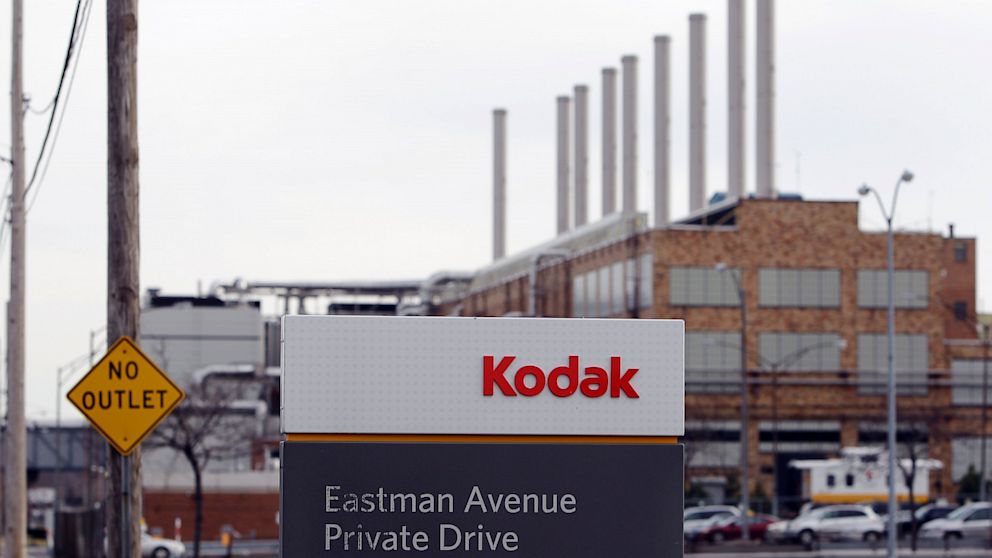

Aug. 22, 2013 -- A Manhattan bankruptcy judge has approved a plan for Eastman Kodak to emerge from Chapter 11 as early as September 3. The new company won't bear much resemblance to the film and camera company of yesteryear, though: It won't, for example, make or sell any products to consumers.

Manhattan bankruptcy judge Allan Gropper, in approving the plan, called it a necessary preliminary to Kodak's regaining what he called "its position in the pantheon of American business."

That position once was high. Kodak, by introducing the Brownie box camera in 1900, virtually invented popular, amateur photography. But last January, after decades of seeing its traditional business first eroded by foreign competition and then eclipsed by digital photography, it sought bankruptcy protection.

Kodak says in a statement that it is transforming itself into a seller of digital printing services to other businesses. That doesn't mean the company's traditional consumer products will disappear; but henceforth, they will be made by another entity, owned by a U.K. pension fund, and yet to be named.

Kodak, to settle $3 billion worth of pension obligations to its former workers in the U.K., is selling its consumer film and camera business to the workers' pension fund. Kodak spokesperson Christopher Veronda tells ABC News the fund has not yet settled on a name for its new enterprise, but that it has the legal right to continue using the name Kodak, if it wants to. "People will be able to continue to enjoy the same products, same name, same look," he predicts.

As for Kodak's remaining B2B digital printing business, Veronda notes that while its services and products will be sold directly to other businesses, those businesses, in turn, will make plenty of stuff that touches the public directly—catalogs, for example, and "eye-popping packaging" consumers will see on grocery store shelves.

The reborn company also will continue to make film for the motion picture industry.

A Manhattan photographer—a serious amateur who for many years has used the company's products--describes himself as "heartbroken" about Kodak.

"Kodak still produces the best film in the world, and will continue to do so, for as long as Hollywood directors prefer the celluloid image to its digital counterpart," he tells ABC. "We consumers benefit from that technology. But when the big boys out West are done with film, it's over for the rest of us. Images will be digital and only digital."

"They still have people with immense skill and who know how to win," Mark Zupan, dean of the business school at the University of Rochester, near Kodak's headquarters, told the Associated Press. "But it's also a team that has gone through hell for the last 10 to 20 years. It has been like constant water torture."

Founded by George Eastman in 1880, Eastman Kodak Co. is credited with popularizing photography at the start of the 20th century and was known all over the world for its Brownie and Instamatic cameras and its yellow-and-red film boxes. It was first brought down by Japanese competition and then an inability to keep pace with the shift from film to digital technology.