Family's Bittersweet Journey Spares One Son From Rare Disease, But Not the Other

Tammy Wilson wants to make sure this doesn't happen to another family.

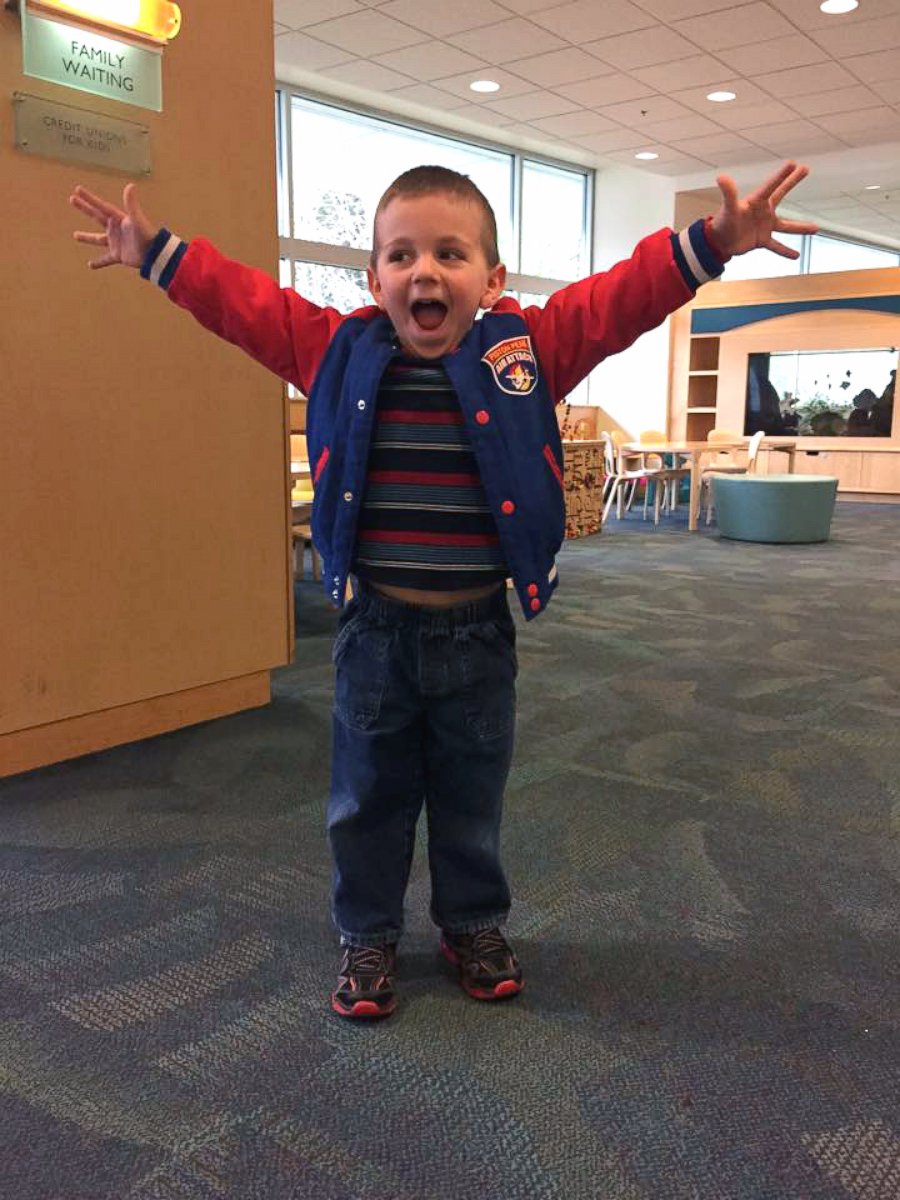

— -- To look at 4-year-old Michael Wilson as he runs and plays and smiles, you would never know he was diagnosed with a terminal illness. That's because a cord blood transplant stopped it in its track, saving his life.

His older brother, Marshall wasn't so lucky.

"My son lost his eyesight. My son lost his hearing. He can't hear me. He can't see me," his mother, Tammy Wilson, told ABC News. "He has seizures on a daily basis, on average six, sometimes 12 seizures a day."

Marshall's decline and diagnosis prompted doctors to quickly diagnose Michael and give him the treatment that would save him.

As a baby, Marshall met every milestone until he was a year old in June 2010, Wilson said. But at 13 months, when Wilson was about 6 months pregnant with Michael, Marshall stopped walking. Then, he stopped crawling. Soon, he couldn't hold up his own head.

It took five months for doctors to diagnosed Marshall with Krabbe, an inherited degenerative disease that would eventually kill him, Wilson said. Doctors immediately told Wilson to test her newborn for the disease as well, and in December 2010, they learned he, too, had it.

Doctors could save Michael by giving him a cord blood transplant, providing him with the enzyme he lacked to maintain the protective coating on nerve cells called myelin. He got the transplant on Feb. 10, 2011, and the Wilsons consider it his re-birthday.

"Marshall was no longer a candidate for this transplant because he was too symptomatic," Wilson said. "From July to December, with the regression he went through as fast as he did, he was no longer a candidate for lifesaving treatment."

Had Marshall been tested as a newborn, he, too, could have been be running and playing with his brother. So Wilson is fighting to get Oregon to mandate a test for Krabbe as part of its standard newborn testing.

Similar legislation has already passed in Illinois, New Mexico, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Missouri, said Anna Grantham, a spokesman for Hunter's Hope, a foundation that helps fund Krabbe research and push newborn testing. Grantham said ten states are considering bills this legislative session.

Wilson's representative in Oregon, Rep. Jim Weidner, sponsored a bill on her behalf last legislative session in 2013, and they hope it will pass this year.

"When there's a cure for something, then we should be testing for it, so we can give a child an opportunity for a full life," Weidner said.

According to the Mayo Clinic, these transplants can help pre-symptomatic infants by slowing the progression of the disease, but they still experience difficulties with "speech, walking and other motor skills."

So far, Michael is doing well. And Wilson said she thinks 5-year-old Marshall is still aware of his surroundings, so she'll press her lips to his cheek to talk to him.

"I’m in full-blown tears because my son is communicating with me," Wilson said. "Which is very rewarding and comforting to me because I knew this disease may take everything from him. ... I know in my heart and soul that he knows I'm mom. I’m thankful for the first year we had together."