Some Health Experts Lukewarm on UN Drug Policy Meeting

"It’s a health issue not a criminal issue," one said.

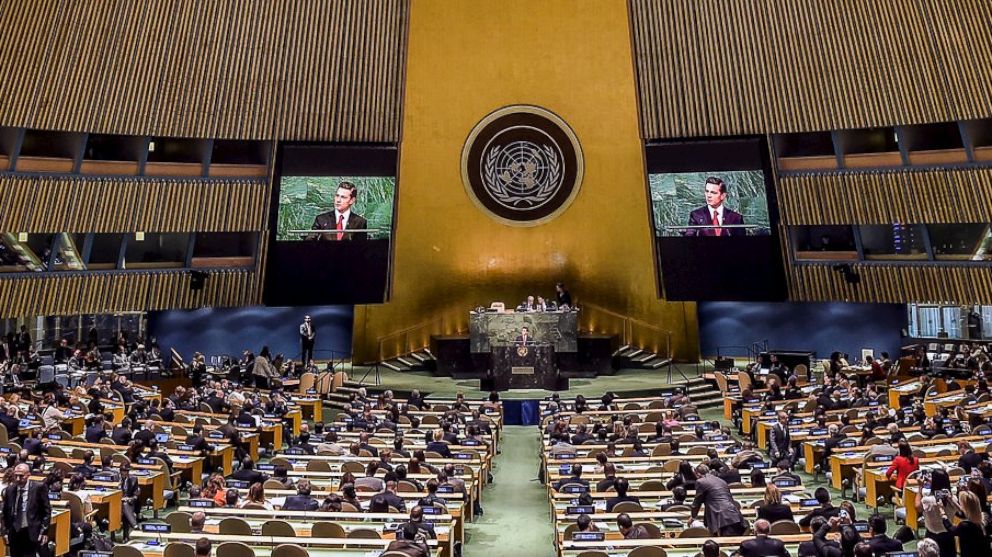

— -- A growing movement to make international drug policy more of a public health issue, versus a criminal justice matter, was central to this week’s United Nations General Assembly meeting on international drug policy.

The UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS), which focused on drug policy, has pushed for a greater public health approach to drug policy, although some experts said they had hoped the assembly would go even further.

The three-day international conference about drug policy reform comes nearly 20 years after UNGASS met for a similar conference under the theme “A drug-free world—we can do it!” The meeting this week was more soberly focused on "addressing and countering the world drug problem.”

The session produced proposals for tackling drug addiction proliferation and associated violence this week with multiple recommendations such as advising member countries to facilitate cooperation between public health and law enforcement authorities to help addicts get treatment, use "evidence-based" strategies to create national drug policies and recognize drug dependence as a complicated health disorder that should be treated at multiple levels with treatment and rehabilitation.

The recommendations fall short of what some experts have wanted, including the lead author of an editorial on drug-policy published in the Lancet medical journal last month.

The Johns Hopkins-Lancet Commission on Drug Policy and Health published the editorial to "encourage a central focus on public health evidence and outcomes" during drug policy debates, including this week’s meeting.

Lead author Joanne Csete, a drug policy expert and associate professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, said she had hoped there would be more of a focus on decriminalizing certain drugs on an international level, especially after countries, including the United States, have taken steps to decriminalize marijuana.

"Not much changed and I don’t think anyone expected much to change," Csete told ABC News today. "I think the more explicit recognition that health and social services be part of balanced drug policy. It’s a small step in the right direction given that it played an almost invisible part of the 1998 meeting."

The commission also called for an end of "prohibition-based" policies, calling them harmful.

"They are portrayed by policy makers to be necessary to preserve public health and safety, and yet they directly and indirectly contribute to lethal violence, disease, discrimination, forced displacement, injustice, and the undermining of people’s right to health," the authors wrote.

In a lengthy document, the commission pointed out that treating drug addiction as a criminal issue and the general prohibition of drugs have resulted in increased risk of overdose, a parallel criminal economy, increasing homicide rates in certain countries and more cases of HIV spread through needle injections.

Instead, the commission recommended that officials involved with revamping drug policy consider decriminalizing minor, non-violent drug offences, focus on policies that give drug addicts access to harm-reduction services such as clean needles, and gradually move to regulate drug markets rather than allow a secondary drug economy to prosper.

Csete said even though some countries at the U.N. assembly talked about public health approaches, she worries that these approaches would include more incarceration than health experts recommend.

"To really scratch the service of what is being called health-oriented reforms, there are too many countries that lock people up for drug treatment," Csete said. "I think we should be very wary of calling things like that public health measures."

At least one other drug-policy expert was hopeful that the meeting is a first step toward bigger changes in drug policy. Daniel Wolfe, director of Harm Reduction at the Open Society Foundation, said he hoped the meeting was just the beginning of a new approach to drug use.

“Previously, the dominant response to drugs was to treat people who use drugs as kind of like drugs themselves, something to be contained or controlled,” Wolfe told ABC News.

“This new ‘public health’ approach focuses less on the illegal nature of drugs, but on drug users as in need of behavior reform. It’s a health issue not a criminal issue.”