When it comes to health, not all states are created equal, report finds

Life expectancy declined for adults in some states -- and it's preventable.

Instead of thinking of the number of deaths illness causes -- think of the number of years illness steals from those who die.

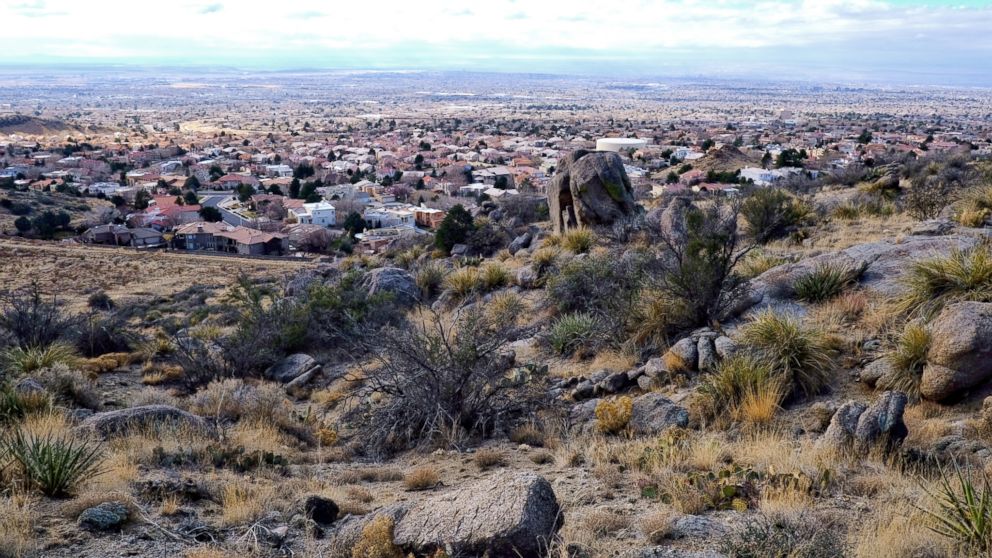

For every 100,000 people living in New Mexico in 2016, 1,466 years of life were lost to heart disease. Although heart disease is the No. 1 killer in America, New Mexico is actually below the national average in deaths from heart disease. So why does New Mexico’s life expectancy rank No. 38 among U.S. states? Again, picture 100,000 New Mexicans. They lost 852 years to the consequences of drug abuse. Nine hundred and three years to self-harm. And 328 years of life to liver disease.

These findings, reported in a state-by-state analysis of the annual Global Disease Burden Survey published Tuesday, can teach us something important: In terms of health, it’s location, location, location; all states are not created equal.

Where do we live the longest? The shortest?

States with long life expectancy are Hawaii, California, Connecticut, Minnesota, New York, Massachusetts, Colorado, New Jersey and Washington. Those with the highest burden of premature death are Mississippi, West Virginia, Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Kentucky.

Hawaii now has the highest life expectancy at birth: an impressive 81.3 years. If Hawaii were a country, it would rank No. 20 in the world. On the other hand, lowest-ranking Mississippi’s life expectancy, 74.7 years, would land the state squarely at No. 76, tied with Kuwait. While some have made major strides in extending their citizens’ lives, others have not -- Washington, D.C., achieved a 42 percent improvement in years of life lost to disease and disability, while Oklahoma saw a measly 6.3 percent rise.

Even more striking, 21 states actually saw higher rates of death among working-age adults in 2016 than they did in 1990. The major cause for this shift? Drug and alcohol abuse, liver disease, and self-harm. These so-called diseases of despair, related to addiction, mental illness and low socioeconomic status, are on the rise, killing people at younger ages than heart disease did. While disease trends differ by state, the dramatic turn of events in these states represent a nationwide problem -- and serve as a warning to the rest of the nation.

Trends in mortality nationwide

The good news? Overall death rates in the U.S. declined between 1990 and 2016. The bad news? Average U.S. life expectancy at birth, which had been increasing since 1993, decreased in 2015 -- and again in 2016. Our advances in treatment for heart disease, cancer and survival of preterm infants are counterbalanced by the next generation of preventable deadly diseases: drug abuse, self-harm, liver failure and chronic kidney disease. The rise of chronic kidney disease can be attributed largely to increasing prevalence of diabetes, which is related to obesity. The others? Those diseases of despair, rooted in addiction and mental illness.

These findings add to a wealth of recent data to support both an increased effort and an evolving focus on preventative medical care. We are seeing the positive outcomes of screening for heart disease risk and cancer. More are using medications like statins and blood pressure pills to prolong life with heart disease, or delay its onset. We’ve developed state-of-the-art medical therapies to help premature infants and cancer sufferers survive to celebrate many more birthdays.

Looking toward preventing more premature deaths

An ongoing focus of public health remains the problem of obesity. Despite improvement in heart disease mortality, obesity remains a top contributor to many of the 20 leading causes of death and disability, most notably diabetes and its related risk of heart and kidney disease, stroke, nerve problems and blindness. Initiatives to improve the diet and exercise habits of Americans to prevent the health consequences of obesity should and will continue.

The next step, it seems, is addressing the underappreciated risks of disability and death due to drug use and mental illness. Enhanced awareness efforts and dedicated resources at the community level can get to the roots of the problem and prevent these diseases from plaguing the next generation as they do today’s.

We have some underused resources as well. Naloxone (Narcan, Evzio) can be used by any bystander to reverse the effects of opioid overdose, yet few know of its lifesaving effect or that many states have implemented programs allowing people to buy it over the counter. Medication is available to cure hepatitis C (often contracted through IV drug use) and prevent subsequent liver disease, yet many with the diagnosis do not seek this therapy and some who want it don’t qualify for insurance coverage.

The Global Disease Burden Survey has provided the U.S. and the leaders of its 50 states with a wealth of information to target a healthy generation of Americans and preserve a healthy lifespan. Now the burden is on us to put that information to use.

Dr. Kelly Arps is a resident physician in internal medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital. She is working with the ABC News Medical Unit.