Why North Korea may be President Trump's greatest foreign policy challenge

Forget Russia or Iran. N. Korea poses a big “existential threat."

— -- Forget Russia, Iran or even ISIS. North Korea is shaping up to be the Trump administration's greatest foreign policy challenge and one the United States can't afford to ignore, some experts say.

Russian cyberattacks and Islamic terrorism have captured much of the international stage, but they do not pose an existential threat to the United States, as North Korea does, according to those experts.

North Korea evolved into the nuclear-armed enigma it is today long before President Trump took office. Now the reclusive, authoritarian state is testing America's new commander in chief with a round of provocative missile tests. The Trump administration must come up with a plan to curb North Korea's missile and nuclear development program, and it must do so quickly, experts told ABC News.

"I don't think there's any doubt that this is one of the most central foreign policy challenges that the new administration will face and is facing right now as we speak," said Evans J.R. Revere, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution's Center for East Asia Policy Studies in Washington, D.C.

North Korea's latest missile launches

North Korea fired a test missile this morning, but the launch failed, according to U.S. and South Korean officials.

"U.S. Pacific Command detected what we assess was a failed North Korean missile launch attempt the morning of March 22 in Korea (12:49 PM Hawaii-time,) in the vicinity of Kalma," U.S. Pacific Command spokesman Cmdr. David Benham said. "A missile appears to have exploded within seconds of launch. We are working with our interagency partners on a more detailed assessment. We continue to monitor North Korea's actions closely."

U.S. officials have still not made an assessment of what kind of missile was fired in the latest launch.

South Korea's Ministry of Defense also confirmed the failed launch. A ministry spokesman initially said four missiles were fired, but he later corrected that figure, saying it was one missile.

The missile was launched near Kalma in eastern Wonsan Province, where North Korea has previously attempted to fire its mobile-launched Musudan intermediate-range ballistic missile. Believed to have a minimum range of 1,500 miles, the missile is of concern to U.S. officials because mobile-launched missiles are hard to track and can be fired on short notice.

U.S. officials said that in recent days activity had been apparent in Wonsan Province, indicating another possible Musudan missile launch was likely.

Earlier this month, North Korea fired five ballistic missiles. One crashed shortly after takeoff March 6, but the other four were detected to have flown about 620 miles and landed in the Sea of Japan. The four missiles flew different trajectories from their launch points, and three of them landed within 200 nautical miles of the coast of Japan, an area that the Japanese government claims as its exclusive economic zone. U.S. officials described them as Scud missiles.

The March 6 launches were seen, at least in part, as a reaction by North Korea to U.S.-South Korean military drills that kicked off a week earlier and have taken place annually for about four decades.

Those launches were practice for a strike on U.S. military bases in Japan that are home to 54,000 U.S. military personnel, North Korean state news agency KCNA reported.

"If the U.S. or South Korea fires even a single flame inside North Korean territory, we will demolish the origin of the invasion and provocation with nuclear tipped missile," KCNA said.

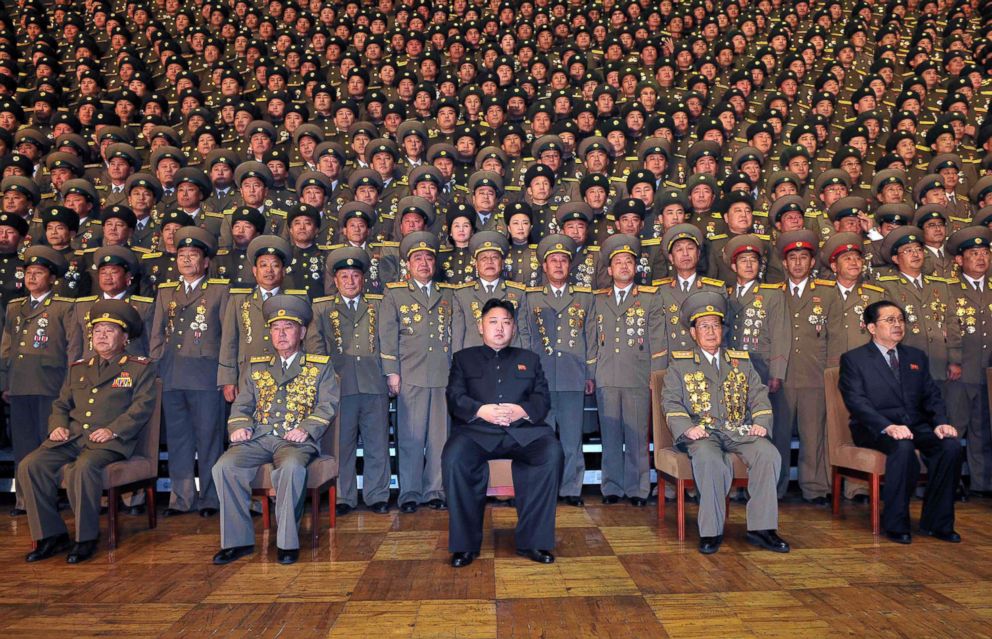

North Korean state television broadcasted images and video of what it said was the country's leader, Kim Jong Un, overseeing the launch of four missiles. State media described Kim as "feasting his eyes on the trails of ballistic rockets."

Trump administration reacts

The U.S. Department of State said it "strongly condemns" the March 6 missile launches, calling the move a violation of United Nations Security Council resolutions. The United States Tuesday began setting up an antimissile system in South Korea.

The U.S. military started delivering the Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense System to its designated site Tuesday. The system is designed to intercept any missile fired at South Korea from the north. The United States had been working with South Korea to install the system since a flurry of missile tests last year by North Korea.

China, which maintains formal diplomatic ties with North Korea, responded quickly by saying it will take unspecified measures against the deployment of a U.S. missile defense system in South Korea and warned that Washington and Seoul will bear the consequences.

During a telephone conversation with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and acting South Korean President Hwang Kyo-Ahn March 6, Trump "emphasized that his administration is taking steps to further enhance our ability to deter and defend against North Korea's ballistic missiles," and the three leaders agreed "to demonstrate to North Korea that there are very dire consequences for its provocative and threatening actions," according to a White House record of what transpired.

At the request of the United States and Japan, the U.N. Security Council held an emergency meeting on North Korea and nonproliferation March 8. But experts said the standard resolutions aren't going to work with North Korea.

"We have to change the game, and the game is we fail to recognize that for North Korea, most of their missile tests and nuclear tests have as much to do with internal politics as external," said Bruce Bennett, a senior international defense researcher at the Rand Corp., a California-based global policy think tank. "You've got to be prepared to get involved in the internal politics."

During a visit to South Korea last week, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson signaled a more aggressive approach to North Korea's missile and nuclear program, including the possibility of pre-emptive military action.

"All options are on the table," particularly if North Korea continues making advances in its ballistic missile and nuclear weapons technologies, Tillerson said at a news conference in Seoul last week.

"If they elevate the threat of their weapons program to a level that we believe requires action, that option is on the table," the top U.S. diplomat said in a comment widely interpreted to refer to the possibility of pre-emptive military force.

Tillerson later indicated that the first step would be additional unilateral U.S. sanctions against North Korea or the full implementation of sanctions imposed by existing U.N. Security Council resolutions.

White House press secretary Sean Spicer Tuesday described the North Korean threat as "grave and escalating," and a National Security Council official told a nuclear conference that the Trump administration is conducting a high-priority review of North Korea policy.

North Korea's nuclear ambitions date back decades

North Korea's nuclear weapons program and its development of long-range rocket systems have been three generations in the making. And the country's standing as a nuclear-weapon-possessing state has even been etched into its constitution.

Kim Il Sung, the country's founder, who ruled from its establishment in 1948 until his death in 1994, dreamed of an intercontinental ballistic missile as the United States threatened to use nuclear weapons against the North during the Korean War.

The Soviet Union, Pyongyang's ally and sponsor, began training North Korean scientists and engineers in the 1950s, giving them the "basic knowledge" to initiate a nuclear program, according to the American Security Project, a nonprofit nonpartisan public policy and research organization based in Washington, D.C.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the death of Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il succeeded his father amid a dire famine that killed up to 2.5 million North Koreans. To protect the state, the new leader developed the songun, or military first, doctrine, under which the military's access to resources is prioritized.

"In this sense, the military is not just an institution designed to perform the function of defending the country from external hostility,” South Korean scholar Han S. Park wrote in a 2007 paper. “Instead, it provides all of the other institutions of the government with legitimacy.”

In July 2006, North Korea tested the Taepodong-2, its first missile that could, in theory, reach parts of the United States. The test failed. Three months later, North Korea tested its first nuclear device near the village of Punggye-ri.

North Korea conducted its fifth nuclear test in September 2016.

Kim Jong Un's reign in North Korea

In a New Year's address, Kim Jong Un said the country was close to testing an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of hitting the U.S. mainland with a nuclear weapon.

"They can't hit us yet, as best as we can tell. But they may only be months to a few years away from being able to do so," Bennett said. "It's getting pretty dangerous."

In February 2017, a U.S. official confirmed to ABC News that North Korea launched a solid-fuel KN-11 missile, described as an intermediate-range missile than can travel 1,400 nautical miles. It was the first land-based test of a missile designed to be launched from a submarine.

Although the test didn't feature an ICBM, the launch indicated North Korea is making progress in developing solid rocket fuel, which is more stable than the liquid fuel Pyongyang has used in its other medium- and long-range missiles. That means North Korea would need less time to prepare, making it difficult for U.S. satellites to track potential launches.

"They have demonstrated a level of sophistication regarding their ability to launch nuclear-capable missiles," Revere told ABC News. "All of the systems they have launched in recent weeks are nuclear capable."

How previous US presidents have handled North Korea

President Bill Clinton tried negotiating a deal with North Korea to prevent it from obtaining nuclear weapons. In 1994, the United States and North Korea announced the Agreed Framework, in which Pyongyang agreed to dismantle its nuclear reactors and associated facilities and accept inspections of all its declared nuclear facilities in exchange for diplomatic and economic concessions from Washington.

President George W. Bush took a different approach to North Korea policy, unwilling to engage with the regime, and thus the Agreed Framework fell apart. In late 2002, North Korea was caught cheating on the agreement and, subsequently, Bush announced the deployment of anti-missile interceptors in Alaska and California, two of the closest states to North Korea.

The Bush administration renewed nuclear talks with North Korea in 2003. But North Korea forged ahead with its nuclear research because, unlike with the Agreed Framework, it did not have to suspend its nuclear weapons program while a final agreement was negotiated.

In 2005, North Korea agreed in principle to abandon its nuclear weapons program. A year later, it tested its first nuclear weapon.

Bush removed North Korea from the State Department's state sponsors of terrorism list in late 2008 and, in return, received nothing after six-party talks — a series of negotiations involving China, Japan, North Korea, Russia, South Korea and the United States for the purpose of dismantling North Korea's nuclear program — fell apart shortly afterward.

President Obama said his administration were willing to revive roundtable talks with North Korea if it was ready to relinquish its nuclear weapons. But this took a backseat to Obama's negotiations on a nuclear deal with Iran, as well as the international war on ISIS in the Middle East.

How will Trump approach North Korea policy?

Trump didn't say much about North Korea during the 2016 presidential election season. On the campaign trail last year, he told Reuters in an interview that he "would have no problem speaking" to Kim Jong Un and that he would "put a lot of pressure on China."

Before his inauguration, Trump responded bluntly to North Korea's claims that it was in the final stages of developing a missile capable of reaching parts of the United States. "It won't happen!" he tweeted.

A month later, North Korea successfully conducted its first missile test of 2017.

"Trump said it won't happen, but he doesn't even have a plan yet for making it not happen," Bennett said. "The North Koreans literally taunted him."

So what can Trump do?

Bennett said, ultimately, perhaps not much, because North Korea has made it very clear it won't give up its nuclear weapons. But he said the Trump administration should come up with a package of solutions to carefully curb North Korea's nuclear capabilities without leading Pyongyang to launch an attack on a nearby country.

For instance, the United States could threaten to drop leaflets soliciting defectors at North Korean nuclear facilities. And if Pyongyang continues launching missiles, the U.S. military may have to start intercepting them, Bennett said.

Experts told ABC News that the Trump administration is researching solutions and policy approaches to North Korea. He is a businessman at heart who doesn't like to lose, the experts said, so he will probably lean toward whichever approach has the highest probability of success.

"The existential threat is not so much it would destroy the entire U.S. anymore but that it would cause enough damage in the United States,” Bennett said. “That would really be unacceptable for any president to allow to happen. North Korea is moving in that direction."

Revere of the Brookings Institution argued that the United States and its partners should undertake a more concerted course of action by implementing an intense program of immediate and overwhelming sanctions that threaten the one thing North Korea values more than its nuclear weapons: the stability and continuity of its regime.

"It would shake the foundation of the regime and do so in such a way that it would cause the North Korean leadership to be deeply concerned that they were putting at risk the continuity of their regime by continuing down this path of nuclear development," he said. "And I'm convinced that in response to that, the North Korean leadership would make the right decision."

And if that doesn't work, then the United States and its allies may have to consider a desperate remedy.

"I'm hoping that would not be necessary. I'm hoping North Korea would look at the logic of coming back to denuclearization talks," Revere said. "But if they don't, it may be regime change is the only mechanism left."

ABC News' Joohee ChoJeff Costello, Benjamin Gittleson, Joshua Hoyos, Alexander Mallin, Luis Martinez, Kirit Radia, Blair Shiff, Paul H.B. Shin and Ryan Struyk contributed to this report, which was supplemented with reporting from The Associated Press.