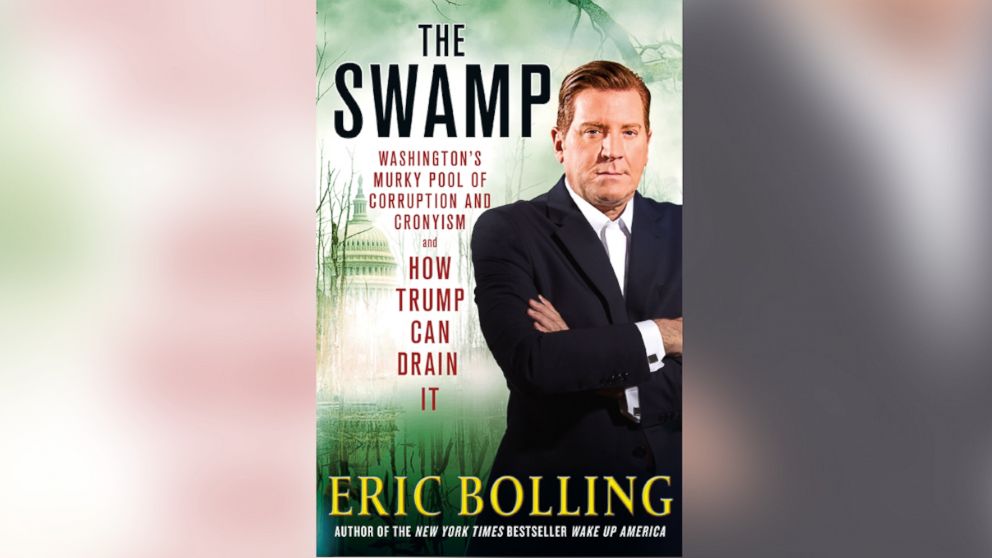

Book Excerpt: Eric Bolling's 'The Swamp: Washington's Murky Pool of Corruption and Cronyism and How Trump Can Drain It'

Read an excerpt of Eric Bolling's "The Swamp."

— -- Excerpted from THE SWAMP: Washington's Murky Pool of Corruption, Cronyism and How Trump Can Drain It by Eric Bolling, with permission from St. Martin’s Press. Copyright (c) Eric Bolling, 2017.

1. INTO THE MIRE

We don’t know exactly what went through thirty-seven-year-old Senator Ted Kennedy’s mind the night of the Chappaquiddick crash. We can guess he was acutely aware of having a smart, athletic twenty-eight-year-old woman in the passenger seat beside him in the car. It wasn’t just lust, he may have told himself. Mary Jo Kopechne was a charming rising star among his cadre of young staff- ers. In the prominent senator’s mind, it was only natural to want some time alone with her. And perhaps he assumed that she would want to spend some time with him: the scion of America’s legendary political dynasty.

He may still have been thinking happily of the party he’d just left behind, where five other married men like himself were partying with five of Mary Jo’s young, single female friends, with alcohol flowing freely. Ted probably didn’t think too much about his mother, who owned the car he was now driving, or the family chauffeur he’d left back at the party.

He was a U.S. senator. He was a Kennedy. He was invincible. He should have given more thought to the darkness and rain that July night in 1969, and to the slightly confusing layout of the road connecting the island of Chappaquiddick to Edgartown on the mainland of Massachusetts.

He stopped at the side of the road for a short time, confused by the route ahead, physically or morally. When he saw a cop approaching the car from behind, the reality of his situation may have come flooding back to him for a moment: It might look bad, a six-year senator from a powerful, high-profile family parking in the dark with a young beauty who admired liberal politicians and had worked for a few, including Ted’s brother Robert, assassinated just a year earlier.

But this was no time to think of death, just of getting back to Edgartown and the hotel. Ted depressed the accelerator, bungled the shift for a moment, and lurched backward toward the cop. Not good. More shifting and the car rolled forward. The cop wandered off, and Ted drove forward, his path seemingly clear for a minute.

But the bridge at Chappaquiddick met the island’s shore at an odd angle. It wasn’t fair, really. Had Ted done anything so wrong? Had he done anything that a man of his stature wasn’t entitled to do?

The car lurched and, for a sickening moment, seemed to hang in the air, then plunged into the narrow channel between Chappaquiddick and Edgartown. So narrow. So small. Yet it would separate Ted from all his ambitions to rise to an office higher than the one he held. How wrong it seems to members of the political class that such petty inconveniences can trip them up.

The car sank into the muddy channel bottom, wheels upward. Water rushed in immediately, and Ted thought with panic about how to save himself. He managed to get out the window. He rose to the surface and floundered over to the bank of the channel, near the bridge.

Ted later testified that he sat on the bank for a while, catching his breath, then began calling for Mary Jo. He shouted her name several times, he said, and got no response. He also testified that he tried several times to swim down to the car, to no avail.

Then, he did what any responsible member of the political elite might do. He decided to go back to the party—but first sat on the bank for about fifteen minutes, wondering if there were some way to keep all this from turning into a scandal. The political elite have learned to live with a great deal of ambient immorality. Scandal, though, is something to be avoided. The public should not get too long a glimpse of what lurks below the surface of the Swamp in the world of politics.

Ted trudged back to the party cottage, neither using a nearby pay phone to call the authorities nor stopping to ask for help at any of several cottages he passed, not even the one with a light on.

Perhaps Ted was in shock from the accident. Or perhaps the specter of death had ceased to hold much fear for this latest ill-fated member of the Kennedy clan. By that night, when Ted stumbled back to the Chappaquiddick party cottage, four of his eight siblings had already met untimely ends, best known among them President John F. Kennedy and his attorney general, Robert, both taken down by assassins.

Ted was the great remaining hope of the family.

At that very same moment that Ted reentered the party cottage, his brother John’s loftiest ambition was reaching posthumous fruition as Apollo 11 made its way from Earth to the moon, having launched just two days before Ted’s crash. The astronauts would successfully travel 239,000 miles and back. Ted only had to navigate the length of an eighty-foot bridge at Chappaquiddick and in all likelihood he would one day have gone on to win the presidency, buoyed by the nation’s desire to recapture the romanticized Kennedy glory days. It was not to be.

Back inside the party cottage, where less than an hour earlier he had borrowed car keys from Crimmins, his family chauffeur, Ted was careful not to alert the others to the circumstances from which he had just dragged himself. He said later he didn’t want to alarm Mary Jo’s friends, nicknamed the Boiler Room Girls, veterans of his brother Robert’s truncated presidential campaign.

We can only speculate how they might have reacted to word of Mary Jo’s accident. They might well have saved her life, though. A local fire department diver, John Farrar, would later testify that Mary Jo did not appear to have been killed by the initial crash but to have been trapped in a small and slowly shrinking pocket of air inside the car. She may still have clung desperately to life, hoping for rescue, even as Ted was asking himself how best to keep the whole thing quiet.

Ted still didn’t call for help from the party cottage. Instead, he collected two of the other male party guests—his cousin Joseph Gargan and Gargan’s friend Paul Markham, a former U.S. attorney. Together, without alerting the women present and without alerting the authorities, they went back to the scene of the crash, where both Gargan and Markham repeated the failed effort to dive down and find Kopechne in the wreck.

The two also tried in vain to convince the sobbing and panicked Ted that he had to contact authorities immediately. Ted told the two men to go back and attend to the other women at the party, that he would alert authorities. He did not.

Instead, apparently still possessing a good deal of physical energy, Ted swam across the five-hundred-foot channel to Edgartown, Massachusetts, part of Martha’s Vineyard and the location of his hotel. The channel swim must have been strangely invigorating and meditative. For a few minutes, he had no moral or political responsibilities, just the almost-instinctive impulse to put hand ahead of hand, kick left and kick right, keep head above water and make it to welcoming land on the other side, a bit farther away from the disaster on the Chappaquiddick shore.

Ironically, Ted was quite comfortable around water. He was competing in the Martha’s Vineyard yacht races that very week, another emblem of membership in the closest thing America has to aristocracy. Safety guidelines say alcohol shouldn’t be used in cars or by people operating boats. Tradition says that drinking and yachting go together just fine.

Soaking wet, Ted made his way to his Edgartown hotel room and collapsed into bed, rising once at about 3:00 a.m. to complain to hotel management about a loud party. The fools had no idea how fitful his sleep was already, without them further disturbing him. You would think that if you had just driven your car off a bridge— likely drowning a young girl (not your wife)—and left the scene, the last thing you’d do would be to complain about some noise in the back hallway of your hotel. Then again: You’re not a Kennedy.

In the morning, Ted was back in his element. All seemed almost right with the world as he chatted in the hotel with the winner of the previous day’s yacht race. Ted felt a fleeting moment of envy. Yesterday was not a victory for him, and the consequences could not be avoided forever. It was now the morning of July 19, 1969.

Ted was joined at the hotel by Gargan and Markham, and he argued with them about his reasons for not yet contacting authorities. The three then took a ferry back to Chappaquiddick Island, where they found no sign that Kopechne had miraculously survived, and so Ted used a pay phone to make several phone calls.

Unbelievably, however, the calls still weren’t to the authorities. Instead, Ted called several friends, asking for their advice. Apparently, he was not yet persuaded by the consensus in favor of him reporting the incident to police. There had to be some way out of this waking nightmare. The rain and dark of the previous night could not possibly be allowed to shatter the sunlit world of a happy, smoothly functioning Martha’s Vineyard. After all, he had a yacht to race. There had to be a solution. He was a Kennedy. There was always a solution.

But by this time, fishermen had spotted the wrecked car and called police, who summoned professional divers to retrieve Ko- pechne’s body. When Ted heard the growing island chatter suggesting that the authorities had already intervened, he realized he must at least keep up appearances of striving to do the right thing. The basic formalities must be given their due, the polite outer forms given a nod. That might yet do the trick. There was no bringing Mary Jo Kopechne back to life, much as Ted had genuinely hoped the whole situation would somehow be rectified by morning with the miraculous appearance of Mary Jo alive and well on another shore—but at least the life of Ted Kennedy might yet be salvaged.

That counted for a great deal, at least in his mind.

Ted headed to the Edgartown police station, while his cousin Gargan went to the party cottage to tell the remaining Boiler Room Girls about the prior night’s crash. Ted told police in a statement that he had been in shock after the accident, that he recalled curling up in the back of a car parked near the party cottage, then walked around a bit before returning to his Edgartown hotel and “immediately” contacted authorities in the morning upon realizing what had happened.

At trial one week later, Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident and received the minimum possible sentence— two months—which was suspended, his sterling prior reputation supposedly a motivating factor in the lenient punishment. His driver’s license was suspended for a year and a half—a terrible hardship for ordinary Americans but not that devastating when you have a chauffeur such as Crimmins at your disposal.

In January 1970, an inquest was held to determine the cause and manner of Mary Jo’s death. It was performed in secret, and the transcript was not released until after the grand jury had met. The judge said Kennedy was “probably negligent,” but the district attorney chose not to prosecute. Three months later, a grand jury was convened. The DA said there was not enough evidence to indict Kennedy, and the grand jury agreed. And so the most prominent member of the Kennedy clan went free to party on Martha’s Vineyard another day.

Somehow, Ted would remain a standard-bearer, and a senator, for another forty years after the crash, until his own death in 2009.

Mary Jo Kopechne, who died one week shy of her twenty-ninth birthday, had been responsible for a campaign region that included her birth state of Pennsylvania. After growing up in New Jersey and getting a business administration degree from that state’s Caldwell College for Women, Kopechne moved to Alabama, participating in the civil rights movement, and soon to Washington, D.C.—then still seen as a beacon of hope and locus of reform by so many well- meaning young people. After a short stint with Florida senator George Smathers, she became part of the secretarial staff for Robert Kennedy, U.S. senator from New York, admired by so many young liberals as the rightful inheritor of the torch that had been carried by his brother John until John’s assassination.

After Robert was assassinated as well, Kopechne might well have experienced enough Kennedy-related tragedy for one lifetime. But there was one more act to be performed, one that would make her story forever part of that political clan’s checkered tale.

In his statements to the press, Ted claimed he had not been drink- ing the night of the crash—and some in the press pretended for years to believe him. His son, former congressman Patrick Kennedy, has asserted in recent interviews that Ted was killed by his severe alcoholism and that he hid prescription medications where he could get them at any time for recreational use and kept vodka in his water bottles. (Familial bad habits would be handed down from father to son, it seems, since Patrick Kennedy fought his own battles with prescription medicine abuse, alcohol, and reckless driving while serving in Congress, eventually compensating by becoming an antimarijuana crusader.)

Back in 1969, Ted’s wife Joan, herself an admitted alcoholic, attended the Kopechne funeral with him, doing her duty and standing by him. Joan had a miscarriage, her third, shortly thereafter and blamed it on stress from the controversy surrounding Chappaquiddick. She stuck with Ted a good while longer, though, before finally divorcing him thirteen years later, in 1982.

This deeply flawed man somehow made it through decades of rather restrained press scrutiny with almost no reckoning for his actions at Chappaquiddick—save the lingering distrust that kept the public from entrusting him with the highest office in the land. He declined to run in 1972 and 1976 despite his high political profile, then failed to secure the Democratic nomination in 1980 when he briefly hoped, perhaps, that the taint of scandal was behind him.

He remained in the Senate until his death twenty-nine years later, regarded as one of its philosophical and intellectual leading lights by many liberals—pleased by his big-spending ways and go-it-alone moves like attempting to negotiate peace with the Russians in defiance of the wishes of then-president Ronald Reagan, an act seen by conservative critics as tantamount to treason. In the wake of that criticism, he urged the voters of Massachusetts to consider whether they thought him still fit to represent them, but he did not resign. He campaigned, usually winning easily, every six years for the rest of his life.

The real issue, though, is not Ted Kennedy’s dubious policy judgments, nor even the precise time line of events that July in Chappaquiddick, but why, time and again, we look to the political figures in Washington as if they are moral leaders. Given the shocking number of politicians and bureaucrats involved in ethical and legal violations, we might be closer to the truth if instead of seeing them as moral exemplars, we thought of them as a criminal class, dwelling in a moral swamp of their own making, from which saner citizens wisely steer well clear.

Neither Kennedys nor Congress members are an aristocracy born to rule us, or even to give us sound advice.

In fact, in 2000, at a time when Patrick Kennedy was chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the police- reporting site Capitol Hill Blue did a study of then-current Congress members’ arrest records and reported that twenty-nine had been accused of spousal abuse, seven had been arrested for fraud, nine- teen had been accused of writing bad checks, one hundred and seventeen had bankrupted at least two businesses, three had been arrested for assault, seventy-one were unable to qualify for credit cards, and eight had been arrested for shoplifting.

Much as we might like to imagine politicians have higher standards than the rest of us—since, after all, they’re so often the ones lecturing the rest of us about what to do—this book will show that they are a good deal worse than you and I.

Oh, and Ted is hardly alone in having trouble behind the wheel. Capitol Hill Blue’s survey found that in 1998 alone, 84 out of 535 members of Congress had been stopped for drunk driving. But in all cases, they were released by the loyal United States Capitol Police after claiming congressional immunity. So long as members of Congress claim they are headed to the Capitol to vote and do the people’s business, they cannot be jailed along the way. They might kill some- one, of course, but they mustn’t be stopped from governing us.

No single day in history is sufficient to indict our entire system of government, but the Chappaquiddick crash was not as unusual as it first appears. Ethical violations are daily business in the swamp that is D.C. Not all the creatures dwelling in the D.C. swamp are characters with as much panache as the Kennedy clan, but that doesn’t make the rest of the Swamp any more pleasant, as I’ll explain.

Would you believe that during the Obama years a U.S. district court judge was arrested trying to buy cocaine from an FBI agent? Or that another was sentenced to jail for two years for lying about sexual harassment? Or that a New York congressman did jail time for tax fraud? Or that a California congresswoman was fined $10,000 for tampering with evidence related to campaign violations?

In just the past few years, members of Congress have also been found guilty of fraud, drunk driving, and racketeering. During these years, a congressional communications director became the first per- son ever convicted of lying to the Office of Congressional Ethics, though it is a safe bet these were not the first lies told in D.C.

During these years, a former Speaker of the House pleaded guilty to paying hush money in order to cover up sex with underage boys. Members of Congress resigned after soliciting sex on Craigslist, having multiple staffers collect fraudulent reelection-petition signatures, sending women lewd pictures, and making unwanted sexual advances. Officials of the General Services Administration, which is supposed to keep careful track of federal government procurements, were fired or resigned over a fun-filled $800,000 weekend at tax- payer expense in Las Vegas.

The litany of these scandals is in turn dwarfed by the better- known gunrunning, terror-attack-bungling, IRS-corrupting, veterans-neglecting, and data-stealing mishaps that characterized the eight years of Obama’s presidency. Those incidents had bigger consequences, but the quiet bubbling of the Swamp—and its usual sexual and financial escapades—goes on in the background, year after year, numbing us to the bigger disasters when they come along.

Read on to find out who all the scoundrels mentioned above are and how the Washington political culture that helped create them works.

What Ronald Reagan saw as a “Shining City” (or at least the capital city of the metaphorical shining city that is America) in fact sits atop a literal swamp, as if its very foundations were evil, like those of the house in Poltergeist. Washington is a city of no-bid con- tracts and general cronyism despite the constant pretense of scrupulous ethics rules and press watchfulness. And it didn’t just get this way recently. The Swamp wasn’t created by this year’s batch of Democrats or by eight years of Obama, nor by the 1960s decadence during which the Chappaquiddick crash happened. It has been this way since the earliest days of the republic, though in many ways it has grown exponentially worse.

Politicians are not demons but neither are they angels, and they are prone to the same vices as the rest of humanity, writ larger and more dangerous by the vast power and the vast resources with which they are entrusted. Time and again, as was likely the case at Chappaquiddick, sex plays a role in their moral stumbles, and we take a look at that troubling pattern next.