Mars Curiosity Rover Findings Fuel Theories of Ancient Life

The Mars Curiosity Rover has detected a methane spike and found other organics.

— -- The Mars Curiosity Rover has measured a 10-fold spike in methane gas and detected organic material that might support the theory that life once existed there billions of years ago, NASA scientists said today.

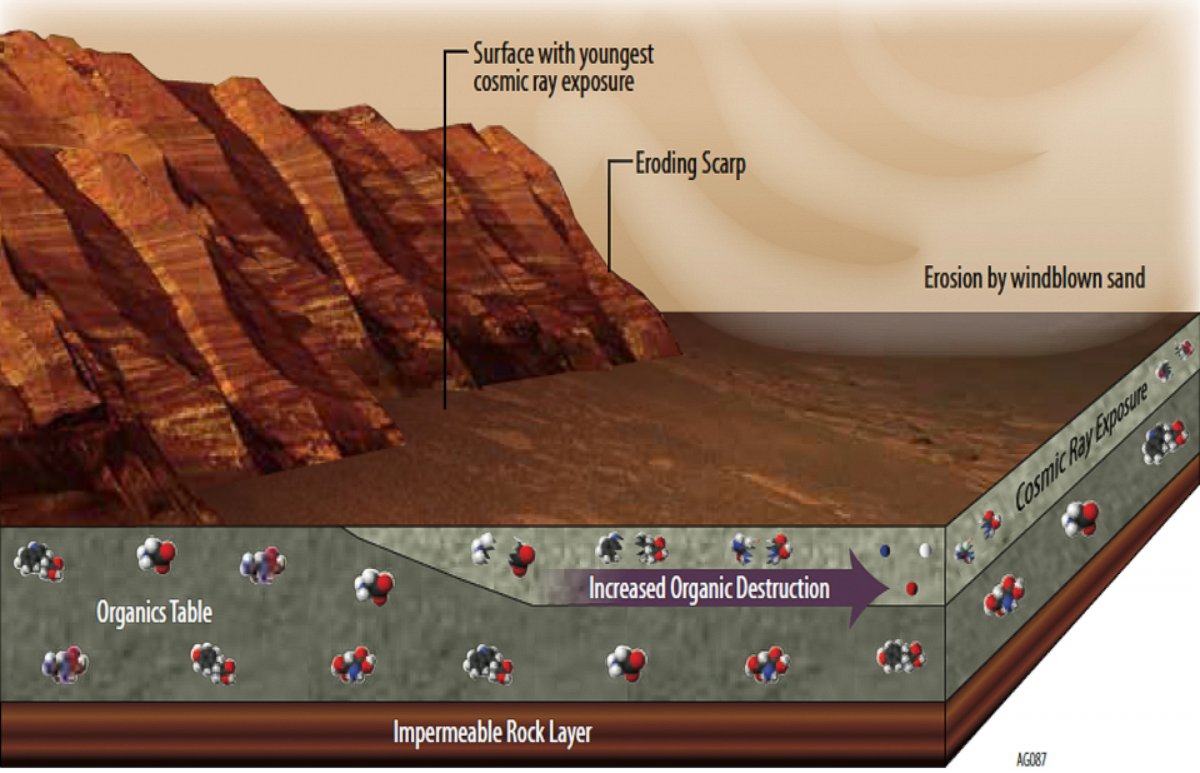

Since its landing in 2012, the robot rover has recorded a spike in methane levels and confirmed the first definite finding of organic compounds in the surface material of the planet through samples dug up from the gale crater, an ancient and now dried up lake on Mars, NASA said today.

The findings support theories that Mars is an active planet that may have once exhibited an inhabitable environment, possibly for some form of life.

"We can't prove it," Danny Glavin, a participating scientist for the Mars Science laboratory who works at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, told ABC News. "But all of these findings are really boosting the case that the gale cratered lake could have supported life."

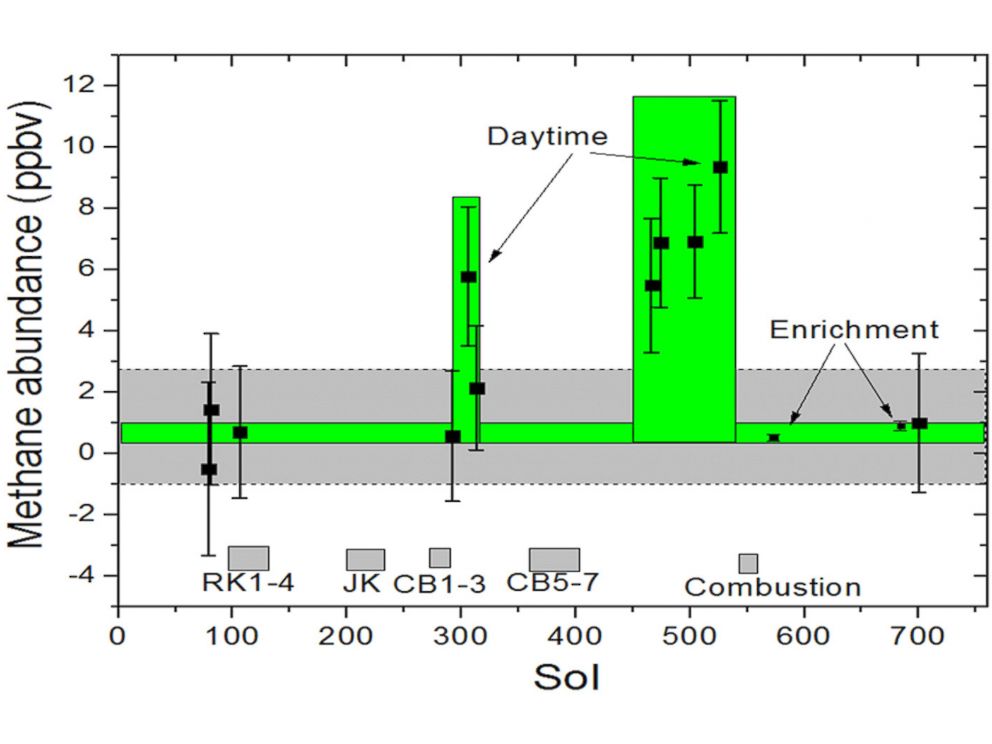

The rover, which has analyzed Martian methane levels periodically, first detected a spike in November 2013 from the average of level of 0.7 parts per billion to approximately 7 parts per billion, remaining around this level for about 60 Martian days and signifying that Mars is still active today, NASA said.

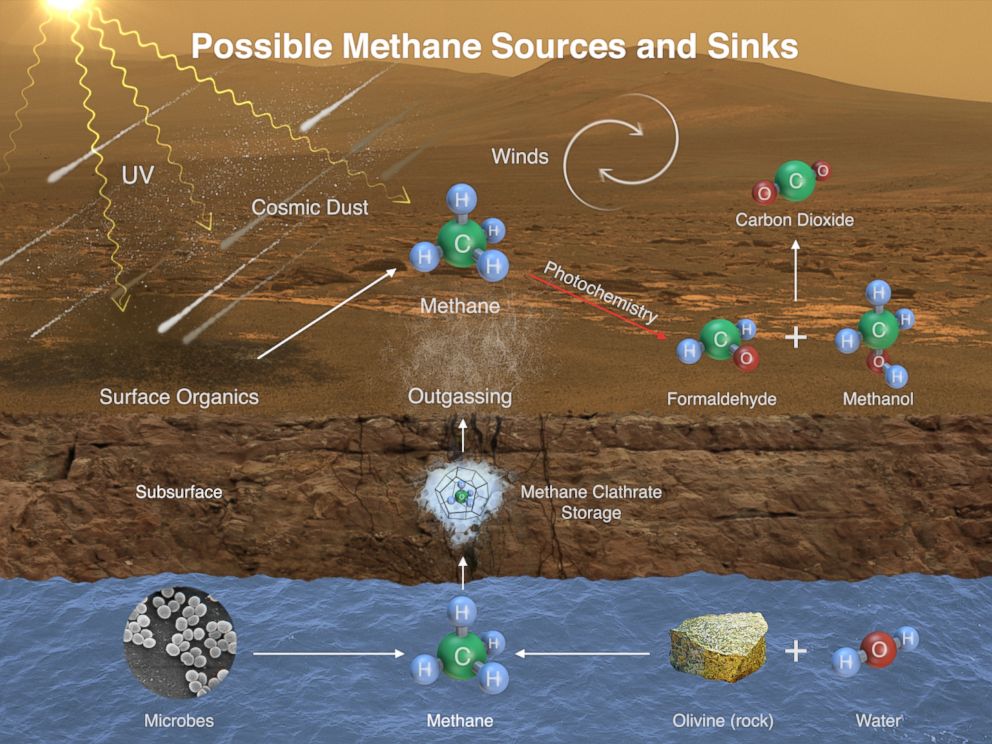

The source of the methane is unknown though scientists have theorized that contact with meteorites and comets, water-and-rock interactions and biological factors could each potentially be sources.

"It's not a dead planet," Glavin told ABC News. "There's some geological reactions, water and rock interactions or particular biology that produced the methane."

The rover took a sample from within the crater in October 2014, finding several organic compounds, suggesting that environmental conditions within the crater could have possibly been sufficient for sustaining life.

"The fact that we've now found organics in this ancient mud rock tells us that conditions in this ancient lake bed were even more habitable than previously thought," Glavin said.

The device also examined the water molecule isotopes that have were sealed within the sample for billions of years. The isotopes showed higher ratios of deuterium, suggesting that Mars may have lost much of its water to space before the Gale Crater seabed even formed, since hydrogen leaves behind deuterium when escaping into space.

Glavin says that discoveries like these are important to scientists who are eager to bring these samples back to Earth for further examination.

"It really sets the stage for future missions," Glavin said.

NASA plans to send another rover in 2020 to Mars to collect and store samples that will be picked up in future missions and transported back to Earth for analysis, according to Glavin.