The Big Differences Between Black and White Families Having the Race Conversation

"Nightline" hosted a diverse group of parents and officers to discuss race.

— -- Two families, living only miles apart in the Philadelphia area, both with dedicated fathers and both with young sons enjoying the summer before seventh grade.

Both dads are middle-class professionals, married and college-educated.

But when it comes to the issues of race, these fathers and sons live in different worlds.

When asked how often he thinks about being a white man, Daniel Kaye said, “I really don’t.” When Solomon Jones, Sr., was asked how often he thinks about being a black man, he said, “Every day.”

“Nightline” first spoke to Kaye and his son Aidan, and Jones and his son Solomon, Jr., in December 2014, during the widespread unrest after a white police officer shot and killed 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, that August.

A year and half has passed since then, and the boys have grown, but so have the country’s problems.

A renewed rallying cry for nationwide protests erupted last week after videos emerged showing the shooting deaths of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, at the hands of police, only to be followed by a sniper targeted officers in downtown Dallas during a peaceful protest for the controversial shootings.

These events have created a fresh wound in the fierce debate over race, policing and the argument over whose lives matter.

“I know that Americans are struggling right now with what we've witnessed over the past week,” President Obama said at the funerals of the slain Dallas officers Tuesday. “First the shootings in Minnesota and Baton Rouge. The protests. Then the targeting of police by the shooter here. An act not just of demented violence but of racial hatred. All that's left us wounded and angry. And hurt.”

For parents like Kaye and Jones, weighing how much of this to expose their children to is very different.

Aidan Kaye, 12, said he had not watched the Sterling and Castile videos, but he had heard about the shootings. Solomon Jones, Jr., 11, had watched the videos and said they hit him “pretty hard.”

“It was, I guess, sad to think about, like, ‘What if that happened to my dad?,’ he said.

Solomon Jr. is a serious child and a good student, but his father worries there could be a moment when that won’t matter.

“We are not people who hate the police,” Solomon Sr., said. “It’s when you go someplace else and the people only know that you’re black...They don’t know that Solomon’s an honor roll student...All they know is that you’re black and so I want my son to be prepared for that fact of life that we still have to deal with in America.”

For Aidan, when asked what the word “police” meant to him, he said he thought of “people who are helping our community and that are trying to make our lives better.”

For Solomon, Jr., the word “police” meant “the law enforcers, people that are supposed to protect us.”

When asked about the word “hoodie,” Aidan and his dad thought of a sweatshirt he throws on sometimes. Solomon, Jr., said “hoodie” made him think of Trayvon Martin.

The 2012 shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin turned the hoodie into the symbol of the danger of being a black teenage boy.

It’s a fear that ABC News Senior Legal Correspondent and Analyst Sunny Hostin knows all too well.

“I have a 13-year-old,” Hostin said. “He's a six-foot tall black kid, and so I have to have this conversation with him. Of course he needs to respect everyone, people in authority. But I also have the conversation with him about how to interact if he ever has a police encounter.”

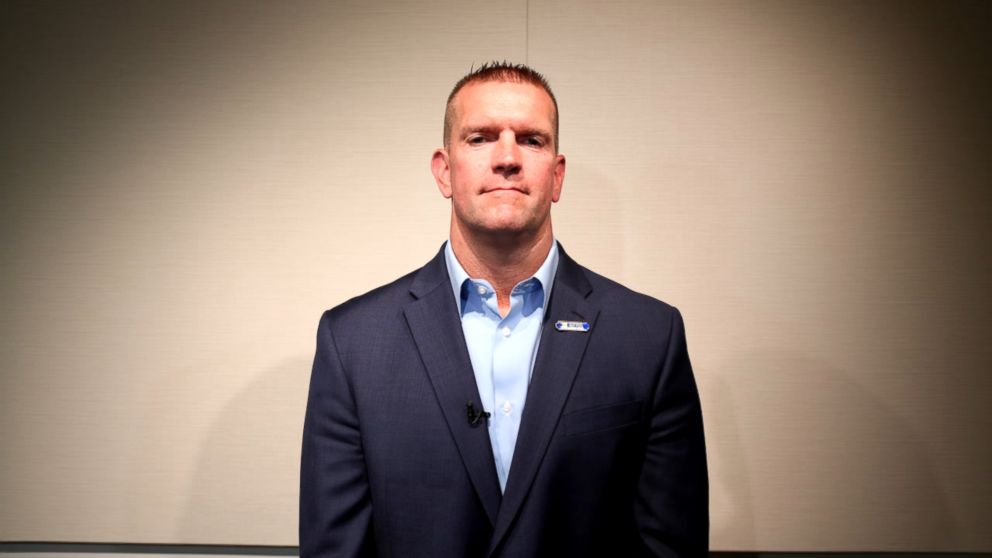

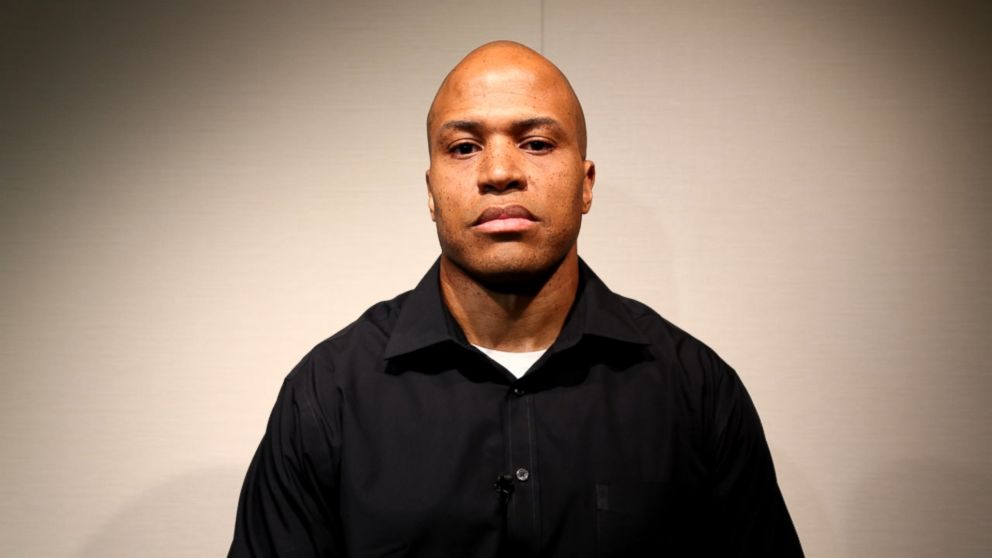

“Nightline” hosted a panel discussion, moderated by Hostin, with a diverse group of Americans: Rasheed Muwallif, an African-American Muslim police officer from Indianapolis, Andy Dwyer, a retired NYPD officer, Sgt. Joey Imperatrice, the founder of Blue Lives Matter NY, both white, Chelsie and Bedford Dort, an interracial couple from Salt Lake City, and outspoken African-American lawyer and author Lawrence Otis Graham.

Graham, a father of three, has written numerous books on race and class. He maintains a strict dress code for his children when they go out in public.

“We have all kinds of rules...particularly with our black boys,” he said. “You don't go out after night, you don't wear the hoodies. You don't wear sunglasses. You don't do anything that somebody can project their biases and stereotypes of what the dangerous black boy is supposed to look like."

Graham also said he tells his children that if they see a police officer, to turn around and walk the other way, which retired Officer Andy Dwyer said wasn’t the best approach. Instead, Dwyer argued, friendly interaction between officers and residents is better to create more understanding.

Dwyer is also a member Blue Lives Matter NY. His brother, also a cop, was 23 years old when he killed in the line of duty while chasing a robbery suspect.

“It's, obviously as anybody would be, a major influence on my life,” Dwyer said. “The guy was Spanish. Did that change my opinion about Spanish people? Absolutely not. It’s ignorant to think like that. But it did make me aware of several things: How precious life is. As a cop any day you might think you're going home that night and you're not.”

One of the major flashpoints in the recent national dialogue has centered on the rallying cry of “Black Lives Matter.” Some critics feel the term is inherently divisive, preferring to say “All Lives Matter” instead.

Graham said that, “Among some communities black lives are not valued as much as white lives. And that's not necessarily focused on the police, but it's focused on people that just don't know black people and not recognizing that as African-Americans, we are twice as likely to have greater force used on us when arrested than when a white person is stopped. So there are certain issues.”

Graham referenced recent comments made by former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who this week called the “Black Lives Matter” movement “racist.”

“He is ignoring the fact that these are communities where people feel that they have been beaten up, or they've been shot and unnecessarily,” Graham said.

Chelsie and Bedford Dort have been married for two years. Chelsie is white, Bedford is African-American. They have a mixed-race child together and Chelsie has a 5-year-old white child from her previous relationship. She said her eyes were opened to the differences her children may face while she and Bedford were still dating.

She recalled times when they would be driving and Bedford would see a cop pull up behind them and he would tell her to take a different road.

“For a long time there was times that I was like, ‘You are being paranoid,’” she said.

But then Chelsie said she got a call one day from Bedford while they were dating, telling her he had been picked up by police for having expired car tags. When she pulled into the police station to get him, Chelsie said she saw six police officers standing around Bedford’s car with their cruiser lights on.

“I just watched them yank him out of his car and just shove him onto the ground… And I could see his face,” she said. “There was a cop kneeling on his back, there was a cop handcuffing him… and we paid to get him out of jail and they impounded his car, and that was the first time that I thought to myself, ‘This is a problem.’”

As an African-American Muslim police officer, Rasheed Muwallif said he understands the issue from both sides.

“There's a lot of black police officers who obviously were black before they were police officers,” he said. "The worst thing that police hear on a daily basis is … a parent will look at the police officer and tell their child, ‘He's going to get you. He's going to take you to jail.”

Often when he and his fellow officers hear that from parents, Muwallif said they will go into their squad cars to get out “a coloring book or a teddy bear, and say, ‘Hey… You don't have to be afraid of us.’ “And maybe the parent doesn't appreciate that after what they said, but we're letting them know, ‘You never should be afraid of the police,’” he continued. “You shouldn't have that fear. Even if your parent had that fear we don't want you to have that fear.”

It’s conversations like these that bridge gaps and can change the way people see each other. As far as creating actual change in our society, Daniel Kaye and Solomon Jones both hope it happens, if not in their lifetimes, than in their sons’.

“I hope that my children will have a future that’s better than mine,” Solomon Sr., said. “That’s what every parent hopes.”

Kaye has a second children’s book coming out in September called, "Never Take a Hermit Crab for Granted," and said he would donate the proceeds to two Philadelphia groups that bring the police and undeserved populations together.

“I have great hope in their generation to be the one to look at it and say, 'alright, this doesn’t even make any sense,'” he said.