Decades after catastrophic 1980 eruption, Mount St. Helens is 'recharging'

The last time Mount St. Helens erupted was in 2008. Now it's recharging.

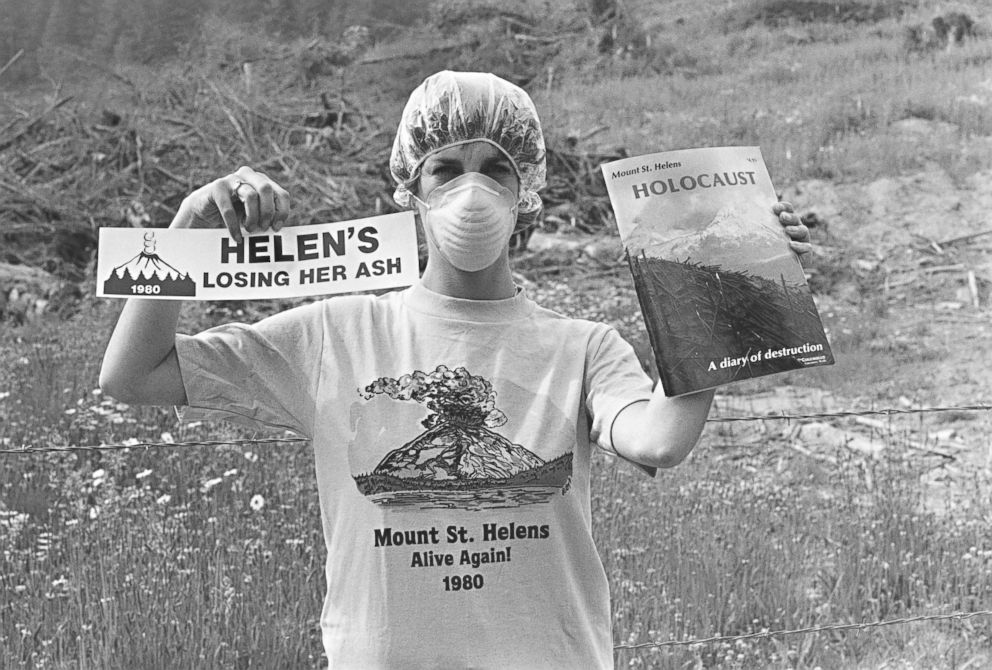

— -- Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980, after two months of increasing volcanic activity.

Since its most recent eruption in 2008, there has been a swarm of earthquakes, which are thought to be a result of the magmatic system's "recharging," according to the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network.

Similar seismic swarms were detected during recharging periods before a small eruption in 2004 and through a period of volcanic activity that ended in 2008.

In March through May of this year, swarms of deep earthquakes, not even felt on the surface, have been detected.

Seismic swarms do not directly indicate that an eruption is imminent, because volcanic forecasting is difficult, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The 1980 eruption is widely considered the most disastrous volcanic eruption in U.S. history. It killed 57 people and destroyed hundreds of homes, 57 bridges and some 200 miles of roads, in addition to leveling tens of thousands of acres of forest.

The eruption sent an ash cloud more than 12 miles into the atmosphere in just 10 minutes. Fine ash reached the Northeast two days later and circled the earth within 15 days, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The volcano had been dormant for more than 100 years until seismic activity started to increase in March 1980.

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

A series of earthquakes caused cracks in the snow and ice at the top of the mountain. On March 27, 1980, ash began to spray from the mountain's peak.

What happened next caught many scientists by surprise. At 8:32 a.m. on the day of the big eruption, a 5.1 magnitude earthquake shook the area, and the mountain's summit and much of its northern flank collapsed, sending a huge explosion out from the north side instead of a typical eruption from the top.

Some 3.2 billion tons of ash spewed into the surrounding area, according to the United States Geological Survey. Streets and buildings were covered, and the eruption caused an estimated $1 billion in damage.

Over the nearly four decades since the cataclysmic eruption, the USGS has noticed signs of recovery near Mount St. Helens.

These signs of regrowth are positive, but there are also signs of increased seismic activity under the mountain.

"Mount St. Helens is at normal background levels of activity," Liz Westby, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey–Cascades Volcano Observatory, told ABC News. "But a bit out of the ordinary are several small magnitude earthquake swarms in March to May 2016, November 2016 and April 16 to May 5, 2017. During the April 16 to May 5, 2017, swarm, we detected well over 100 earthquakes, all below a magnitude 1.3."

Those quakes originated between sea level and 3 miles below sea level and were too small for people to feel on the surface, even if they had been directly above them, she said.

Even though there has been a swarm of earthquakes, Westby said, that doesn't necessarily mean that an eruption of Mount St. Helens is coming soon. Volcanic forecasts can be tricky.

"There are several reasons why it is very unlikely that this swarm is a precursor to imminent eruptive activity at Mount St. Helens. It is similar to ones in the past that did not lead to surface activity. It consists of very small earthquakes occurring at relatively low rates. There are no other geophysical indicators (like surface deformation, tilting, increased volcanic gas emissions) of unrest," she told ABC News.

Westby said these swarms are extremely interesting and helpful to scientists, since each geophysical signal gives them a better understanding of how a volcano functions.

"This is why we maintain a close watch over these giants, so we can detect the earliest signs of reawakening," she said.

The agency sends out weekly updates on seismic activity around the volcano. Mount St. Helens' last eruption in 2008 was insignificant compared with the devastating eruption in 1980.