Letters Found in Cereal Box Show Rare Look at German POWs After WW2

A rare discovery shows letters written by German POWs held in Tennessee.

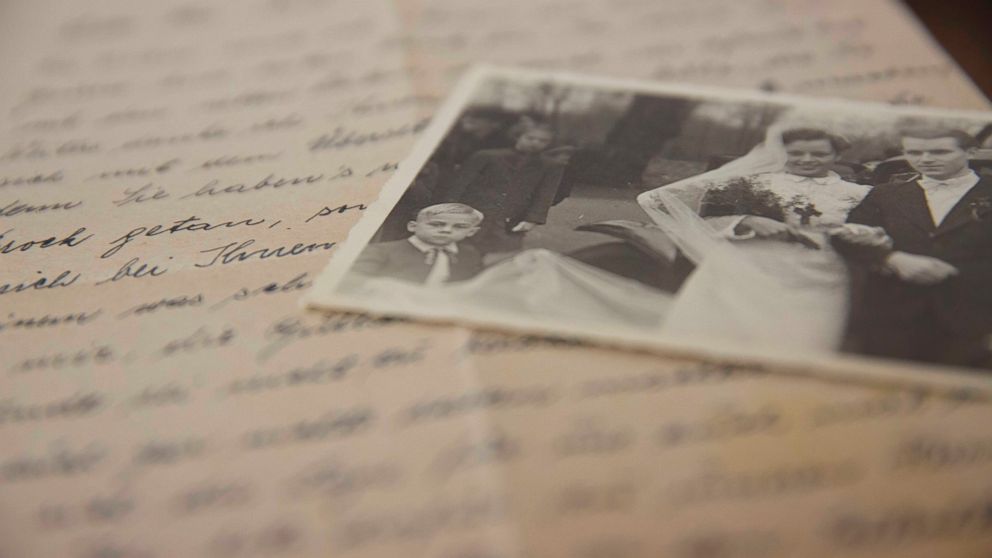

— -- Letters found in a Corn Flakes cereal box reveal intimate relationships between German prisoners of war and the Tennessee locals who lived and worked among them.

Curtis Peters of Tennessee said his sister-in-law in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, found some 400 letters in the home of her great-aunt when she passed away in the late 1980s. The letters, written by German men who lived in a prison camp near Tennessee's southern border after World War II, are "social history, about their lives, their families, the hardships they suffered," said historian Tim Johnson.

"It was a different world," said Peters, a retired high school history teacher who is president of the Lawrence County Historical Society.

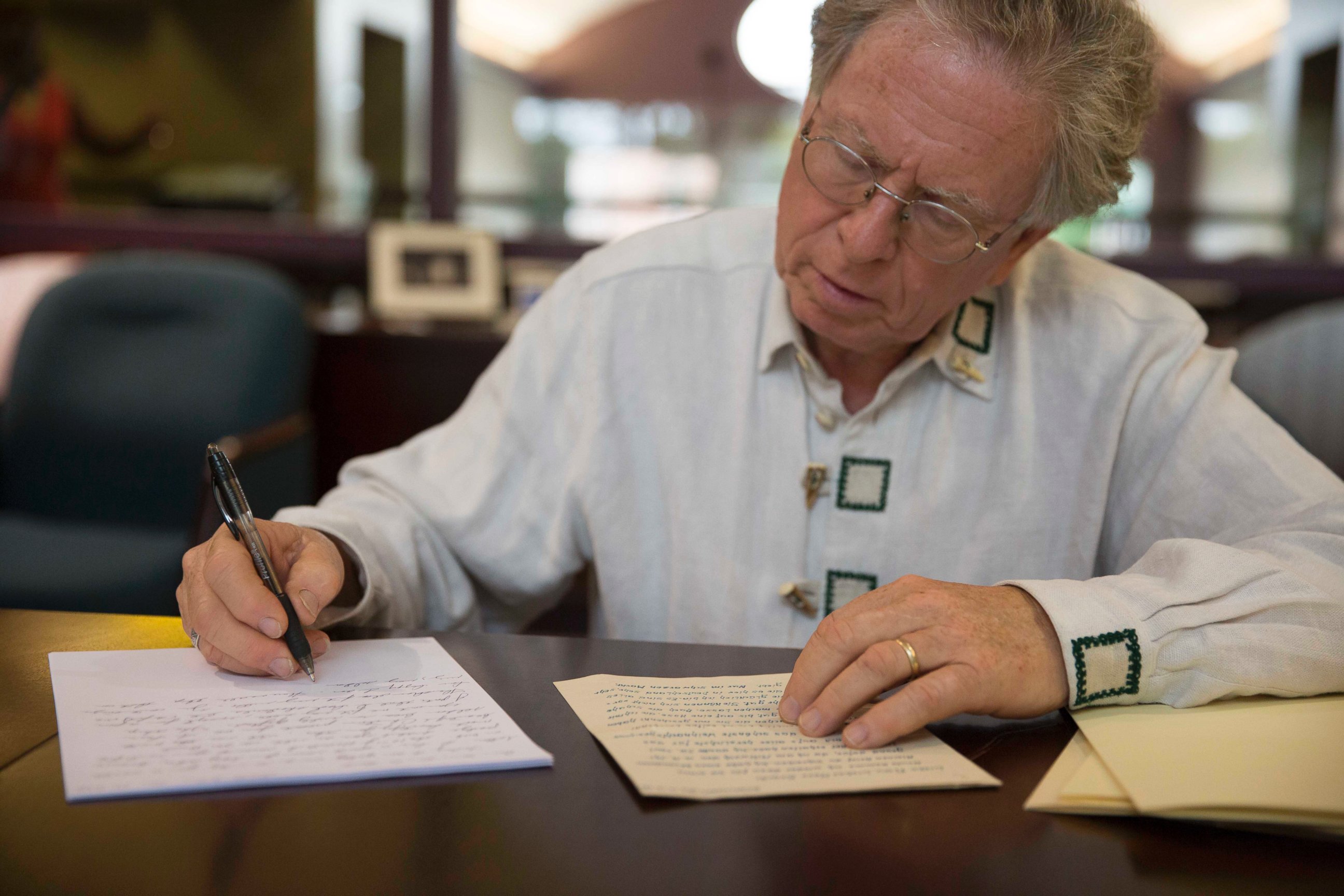

The family eventually donated the letters to Lipscomb University in Nashville after Peters happened to meet one of their history professors, Tim Johnson, while he had breakfast at a diner.

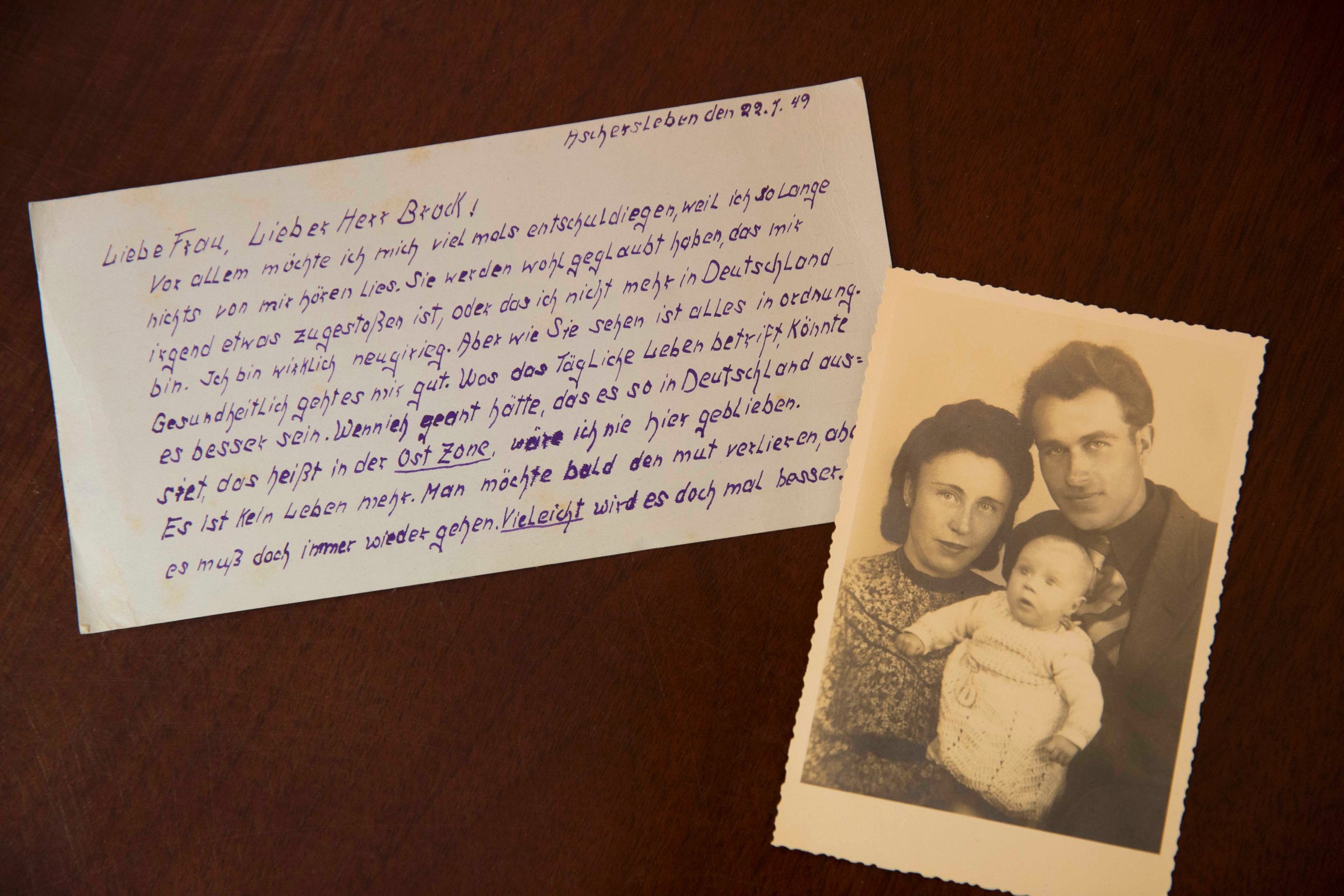

The letters were written between 1946 up to a Christmas card sent in 1976.

"For that long after the war, they show that’s how close the relationship was," Peters said. He said he believes the 330 or so German prisoners held at the camp were held separately from those who were Nazis. According to local newspaper accounts at the time, Peters said, "The tone changed from calling them Nazis to German soldiers to German boys over a two-year period of time."

In the earliest letters, the German prisoners, who worked on the property of the Stribling and Brock families, ask the Americans for help. Peters' wife and her great-aunt were related to the Stribling and Brock families.

One German prisoner eventually became a dentist in war-torn Germany and asked for medicine for his patients or clothes, which were limited to a black market there. But the letters, which address Americans as family, such as "aunt" or "uncle," show the relationships turned into friendship, Peters said.

One of the letters that stuck with Peters the most was written by the former prisoner Willi Mueller, dated Sept. 3, 1948: "I think there would be no war and enemies in the world if the different nations could understand so well as we did. We paid dearly for starting and leading the war. I wished everybody could forget the war and the bad things that happened in it and try to live in peace and respect as neighbors. The whole world would benefit from that."

“I really thought this should be available to the public," Johnson told ABC News. "It’s unusual to find this large of a collection of letters.”

The Tennessee Historical Records Advisory Board and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission gave a $1,250 grant to assist in digitizing the letters. Lipscomb University provided a summer faculty grant for German professor Charles McVey to translate the letters. Both of the original parties wrote in their native language and the recipients would find people to help translate them, Peters said.

“It’s easy to talk about war when it is at a distance," Johnson said. "Part of war is to dehumanize your opponent. When you bring in the human element, it’s a completely different ballgame. These letters bring you face-to-face with humanity.”

The library plans to feature them in an event to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

“Many American only know WWII from Brad Pitt and Tom Hanks movies," McVey said. "Even though I’m a German professor and my father was a POW in Germany, I knew some Germans were POWs here in American, but it never occurred to me that German POWs were so close to our area. Through this project, we are finding people all over the U.S. who knew of these camps and knew Germans housed in them. These letters are really bringing something that was old and forgotten to life again."

McVey said that the significance to the university is its library may become a center for the study of this aspect of World War II.

"It’s a very interesting topic tied to military history but also tied to how people relate to each other today in conflict and in imprisonment," McVey said. "We’ve discovered that people all over are aware of this history, but there doesn’t seem to be a nexus for the study and collection of information on this topic.”