‘Negro’ D-Day Hero Overlooked for Medal of Honor

Widow: “Never too late” to do the right thing by medic Cpl. Waverly Woodson, Jr.

— -- The faded, type-written piece of paper was buried in a box of 70-year-old documents at a presidential archive, but after it was recently unearthed, the fragile paper shined a spotlight on what a history detective called an injustice that lingers on from the Second World War – that of some black heroes who fought, but were forgotten.

“Here is a Negro from Philadelphia who has been recommended for a suitable award... This is a big enough award so that the President can give it personally, as he has in the case of some white boys,” stated the 1944 U.S. War Department memo to the Franklin D. Roosevelt White House.

The memo was written about Army Cpl. Waverly Woodson, Jr., and the “suitable award” important enough for Roosevelt to consider personally giving Woodson was the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award given for valor. It would recognize his heroic actions as a combat medic on Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944, during the first hours of the Allies' D-Day invasion of Europe.

But Woodson, who was black, never received the Medal of Honor or the Distinguished Service Cross, the military’s second-highest honor. Now his family, with the help of the author of a new book on his unit and a sympathetic congressman, are trying to restore and highlight a page erased from the history of the Greatest Generation by requesting the Medal of Honor be finally given to him.

"It's never too late. It's always possible to right a wrong. We need to let the future generations know what happened in World War II. The younger generation doesn't even know what World War II was," Woodson's widow, Joann, told ABC News in an interview on Tuesday, two days before President Obama is scheduled to bestow a Medal of Honor on a veteran of the War in Afghanistan.

Joann's late husband, who went by "Woody" and died a decade ago, had been a combat medic with the Army's all-black segregated 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion and saved dozens, if not hundreds, of troops on the battle-ripped landing area known as Omaha Beach, the stretch of coastline that saw the worst fighting on D-Day. Instead of the highest distinction or the DSC, he received the Bronze Star Medal, the fourth-highest individual military honor.

No records have survived to explain why Woodson was denied a White House ceremony presided over by FDR to receive the Medal of Honor. But one fact remains: not one of the hundreds of thousands of African-Americans who served during World War II received the Medal of Honor at the time.

It wasn’t until 1997 that seven black troops from World War II were given the Medal of Honor by President Clinton, but Woodson was not among them. Woodson, like 16-18 million other soldiers, lost all of his military records in the infamous 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis.

That is, until the Philleo Nash memo was discovered.

"It was tucked in voluminous folders inside dusty boxes," Linda Hervieux, author of the new book, "Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, at Home and At War" told ABC News in an interview.

It was Hervieux who discovered the 1944 memo at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library. It was written by War Department aide Philleo Nash to a colleague, which is the only surviving record known to exist regarding Woodson, who was described in newspapers that served the African-American community in 1944 as the "No. 1 Invasion Hero." Hervieux spent five years researching her book on Woodson and his outfit, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion.

Nash was an assistant director in the Office of War Information and wrote the typed page as a memo to Jonathan Daniels, a Roosevelt White House aide. Nash wrote that Woodson’s commanding officer had recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross, but the office of U.S. Gen. John C. H. Lee in Britain had upgraded the recommendation to the highest decoration.

"Something happened between his commanders deciding he should get the Distinguished Service Cross and be upgraded to the Medal of Honor, but we don't know what because those records are no longer there," Hervieux said. "But Waverly Woodson's heroics on Omaha Beach were clearly ignored and forgotten because the Army was racist to its core."

Woodson’s little-known Barrage Balloon Battalion was responsible for hoisting huge balloons on the front lines of Normandy, France in an effort to deter German fighter planes from strafing or dive-bombing the infantry, Hervieux recounts in her book.

As a combat medic in the battalion, Woodson fought to save wounded and dying American troops, black and white alike, he was hit by shrapnel in the leg and buttocks but kept working.

“At that time,” Woodson once told an interviewer, “they didn’t care what color my skin was.”

In her book, Hervieux writes, “Throughout the day and night and into the next day, Woodson worked through his pain to save lives. He pulled out bullets, patched gaping wounds, and dispensed blood plasma. He amputated a right foot.”

Hervieux describes Woodson as the 320th’s "undisputed hero," continuing to save lives during the invasion assault despite being seriously wounded by shrapnel. After another medic slapped a dressing on his leg, Woodson later recalled wisecracking, "Close. Mighty close."

Then, after resuscitating another four drowning men, 30 hours after he landed on Omaha Beach, Hervieux said Woodson “collapsed.”

His widow, Joann, now 86 herself, said she married a hero, even if discrimination in the era of Jim Crow left him forgotten by history for decades.

"That's the kind of man he was," Joann Woodson told ABC News on Tuesday from her home in Clarksburg, Maryland. "He was dedicated. Under fire, I don't think he thought about it -- his own safety."

In an interview with ABC News’ "World News Tonight" on the 50th anniversary of D-Day in 1994, the humble former medic said he just did his job on that beach.

"There is no hero. It's just that you're there and you do what you can," Woodson said then.

He didn't learn until three years later, when a White House-assembled team of historians informed him, that he had even been under consideration for the Medal of Honor back in 1944.

During World War II, the Allies fought Nazis obsessed with racial genocide -- but the American military also was full of pervasive racism. Black troops served only in segregated units, though countless fought and died heroically alongside their white comrades-in-arms.

"We are written out of history, man -- with intent. As a result nobody knows about our history. They were just heroic people who were under the specter of being 'less' by those who wrote the history," said Wheelock College professor and documentarian William "Smitty" Smith, who knew and interviewed many 320th men, including Woodson before his death.

He said Woodson never mentioned learning in 1997 that he was up for the Medal of Honor, which is usually given posthumously to those who make the ultimate sacrifice to save the lives of their battle buddies in combat.

"This guy was so modest. He didn't bring it up with me. He described what he did on D-Day but it wasn't with braggadocio," recalled Smith, who directed a 2000 documentary featuring Woodson, "The Invisible Soldiers: Unheard Voices ."

Despite Woodson's fame within Black America during the war, Hervieux said she found the history of the 320th was all but erased, as she tracked down the handful of men who had served in the unit and the few remaining photos and documents.

Three weeks after the D-Day invasion, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, hailed the 320th in a commendation for the "splendid manner" in which they raised their balloons under the hardcore onslaught of the Wehrmacht on the cliffs of Normandy.

"Despite the losses sustained, the battalion carried out its mission with courage and determination, and proved an important element of the air defense team.... I commend you and the officers and men of your battalion for your fine effort which has merited the praise of all who have observed it," Eisenhower stated in a memo.

But the 1944 memo found by Hervieux in the Truman archives written by Philleo Nash -- who went on to oversee racial integration of military units as a top aide to President Truman -- survives as the only smoking gun for those who wish to see Woodson honored, along with all those men of color who fought and bled red just like their white comrades did in World War II.

"In light of this evidence, I urge you to review Waverly B. Woodson, Jr.'s record of service and authorize the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor to him," Rep. Chris Van Hollen, a Democrat who represents the Woodson's family's Maryland district, wrote this week to the acting secretary of the Army, Erik Fanning.

Calling Woodson "one of the true heroes of World War II,” Van Hollen cited Hervieux's "new evidence" in the book "Forgotten" and urged the Army to right a 71-year-old wrong.

Army spokesman Wayne Hall would not say if Woodson is being considered for the full honors he was denied, but explained that, "All recommendations must be processed to at least the first disapproval authority. If the Secretary of the Army recommends approval of the award of the Medal of Honor, the recommendation is forwarded to the Secretary of Defense for his action and subsequently forwarded to the President if the Secretary of Defense recommends approval."

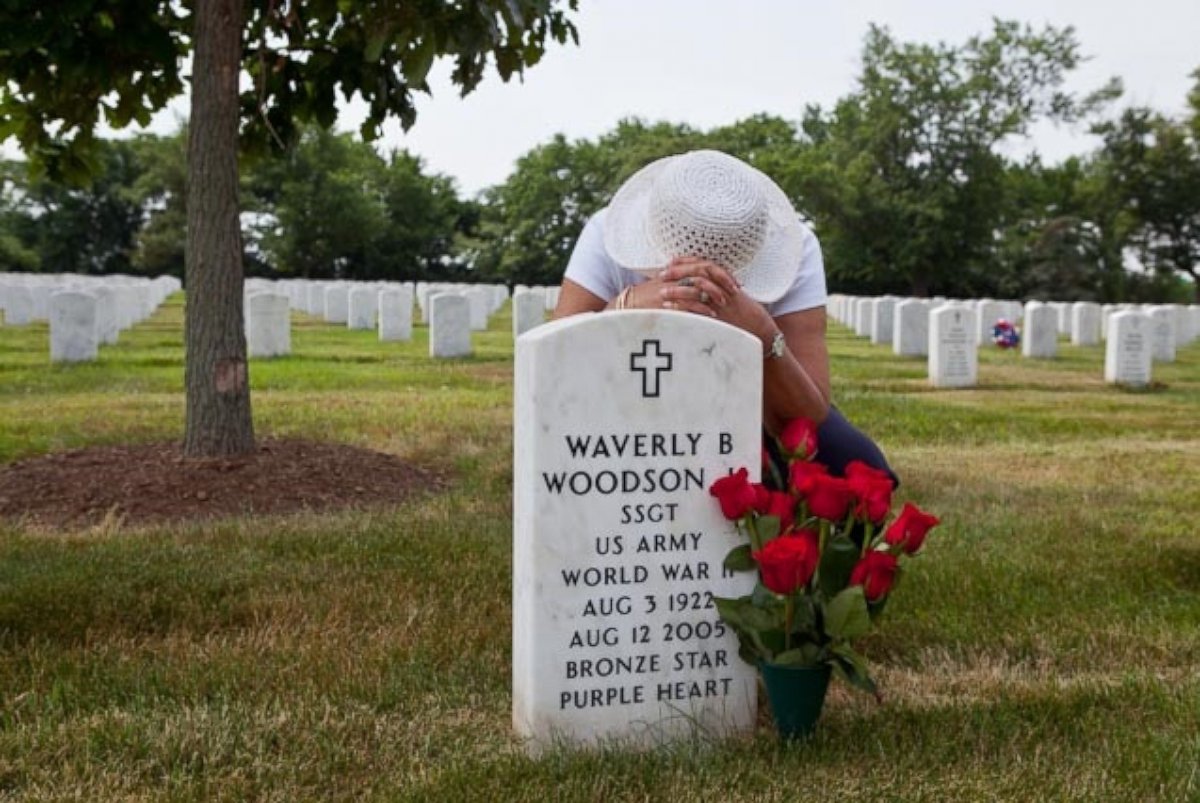

Joann Woodson still regularly visits her husband's grave at Arlington National Cemetery, where she places the red roses he loved to grow just for her.

On the 50th anniversary of D-Day, the government of France invited the couple to participate in ceremonies at Normandy, where he walked Omaha Beach for the first time since June 6, 1944.

"He walked along and would look out over the water. He told me the noise was deafening that morning. He said, 'My buddies are gone'," Joann recounted. "All the memories surfaced. I asked him, 'Are you sure you want to continue down the beach?' He said, 'Yes.' I held his hand and he and I walked down the beach."

ABC News' Zoe Lake, Annie Shi and Luis Martinez contributed to this report.