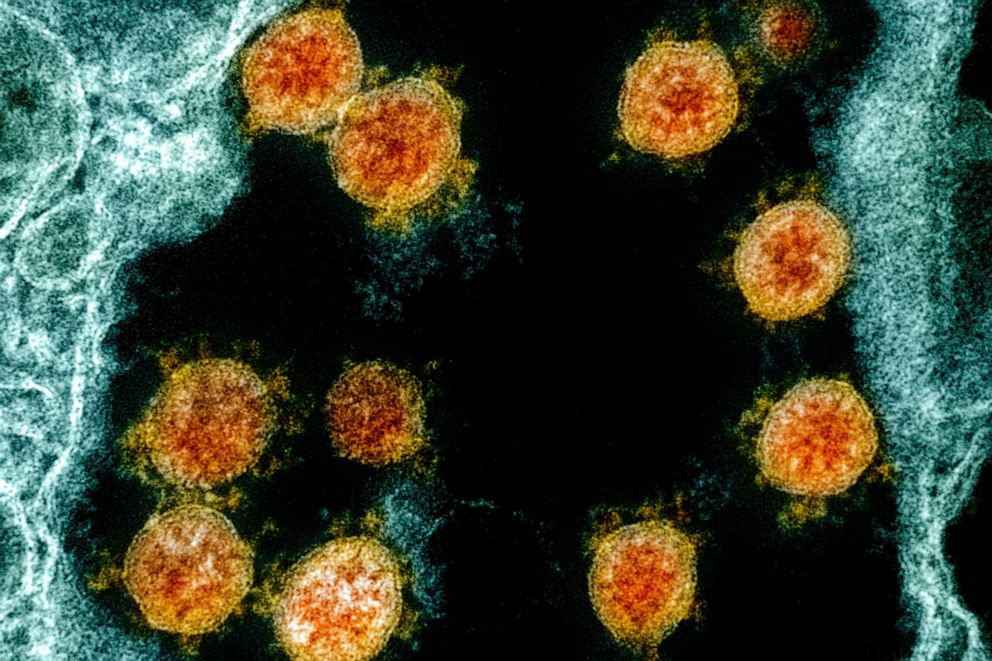

1st documented COVID-19 reinfection isn't surprising, but may offer important clues about virus, experts say

Doctors say the virus's ability to strike a person twice is no cause for alarm.

Back in March, as the novel coronavirus was still stretching beyond China to all corners of the globe, a 33-year old man from Hong Kong came down with a fever and a cough.

He spent two weeks in a hospital battling COVID-19, but by mid-April he had recovered, his doctors reassured after two consecutive COVID-19 tests that scan for signs of the virus' genetic code inside the body came back negative.

In August, the man traveled to Spain, stopping for a layover in the United Kingdom -- two countries at the time grappling with their own wide community spread. When he returned home to Hong Kong, he tested positive for the virus, again. The second time around, however, the man felt fine. His temperature, breathing and blood pressure levels were all completely normal. He didn't feel sick, but he was. He may have been symptom-free, but COVID-19 was back in his system.

In what scientists are calling the world's first documented reinfection, researchers in Hong Kong are telling and investigating the story of the man, who seemingly recovered from the virus, only to become infected again, nearly five months later.

Specialists interviewed by ABC News are urging the public not to panic, noting that reinfection was always a possibility, just like the common cold.

"There isn't anything alarming about this at all," said Dr. Dan Barouch, the director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. "It's an interesting and important case report. It answers the question [of] whether it's possible to get re-infected: The answer is yes."

Although there have been isolated case reports of reinfections since the start of the pandemic, experts say those stories may not have been true reinfections, possibly chalked up to false positives, or prolonged "viral shedding."

But for the first time, researchers in Hong Kong were able to isolate the precise genetic sequence -- almost a viral fingerprint -- of this patient's first infection, comparing it to that of his second infection. If the two genetic "fingerprints" had been a match, this too may have been written off as a strange aberration. But they didn't. In fact, experts said his first infection was from a version of the virus circulating in China, while the second was likely from another version circulating in Europe. This confirmed it was, indeed, a second infection.

"I think the further out you go in this pandemic, you're going to see more and more of this," said Dr. Paul Goepfert, a professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and an expert in vaccine design. "I don't think this is the end of the world. I think it's just an interesting phenomenon that should have been predicted from what we know about coronavirus."

Specialists said reinfections like this are probably still rare, and one man's experience with COVID-19 is unlikely to be the average person's experience.

"If this were a common thing, we would have probably seen it more by now," said Dr. Charles Dela Cruz, an associate professor of medicine and of microbial pathogenesis at Yale School of Medicine. "We're eight months into this whole thing… this might suggest that you can have a reinfection, but it's possibly a rarer incident."

"There are always rare events and people with unusual responses to pathogens," agreed Dr. Richard Kuhn, the editor-in-chief of the journal Virology, and a distinguished professor in Science in the Purdue University Department of Biological Science.

There's some evidence that the man who became reinfected didn't mount a robust antibody response -- the biological army of tiny proteins that swarm bodies under attack from a viral invader. After 10 days of having COVID-19 the first time, a blood test revealed he did not have antibodies in his system. So, people who do see a strong antibody response may not have the same experience if exposed again.

Still, the specialists who study virology said the case study offers interesting clues about exactly what happens if you do become reinfected, suggesting that the first infection could offer a weakened form of protection, if not full immunity.

Every virus behaves differently, specialists explained. Some, such as those that cause measles and rubella, only touch us once. If you're lucky enough to recover, you're believed to be protected for life. Others, such as HIV, embed deep within our cells and never leave.

And others -- including the family of coronaviruses which SARS-COV-2 belongs to -- are more like infrequent, unwelcome visitors, able to reinfect our bodies after a burst of natural immunity that slowly fades after the first infection.

But there is a silver lining: Recover from that first infection, and you're less likely to get very sick the second time around.

"Notice that the man did not get sick on the second infection," said Vincent Racaniello, Ph.D., a Higgins professor of microbiology and immunology at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine at CUNY.

"It is exactly what was predicted would happen months ago, based on how the seasonal [coronaviruses] work," he said. "Immunity wanes after less than a year. [Possible] reinfections occur every year, but they are mild."

"I think the reassuring thing about this is that the second infection was really asymptomatic," agreed Dela Cruz.

Although reassuring in some ways, some doctors interviewed by ABC News said this new information raises thorny questions about the various versions of the virus that are circulating in different parts of the world: the minor variations on the SARS-COV-2 virus.

After the novel coronavirus first emerged in China, it began to travel across the globe, hitching a ride with international travelers, many of whom were unaware they were infected. Along the way, it developed tiny mutations, not big enough to change its behavior in a meaningful way, but noticeable to the watchful scientists vigilantly scanning its genetic code.

Now, some scientists are speculating these tiny variations could have played a role in the reinfection of the young man from Hong Kong.

"Your immune response is trained to recognize the first virus after initial infection, but then it might not be so good at recognizing a different version of that virus later," said Dela Cruz.

But for now, experts are merely speculating about the various versions of the virus, and whether immunity to one offers protection from another.

Beyond these theories, experts have a growing level of confidence -- based on recent evidence -- that when scientists do find a working COVID-19 vaccine, we may all need to be periodically re-vaccinated.

And with so much uncertainty, Goepfert said, "the most prudent thing is to act as though you are not protected," even if you're recovered from COVID-19.

"If it were me, I would still want to wear a mask," Goepfert said. "It's no fun getting infected with that virus."