How did coronavirus get transferred from animals to humans? Scientists may have an answer

Experts insist there is evidence the virus was not man-made.

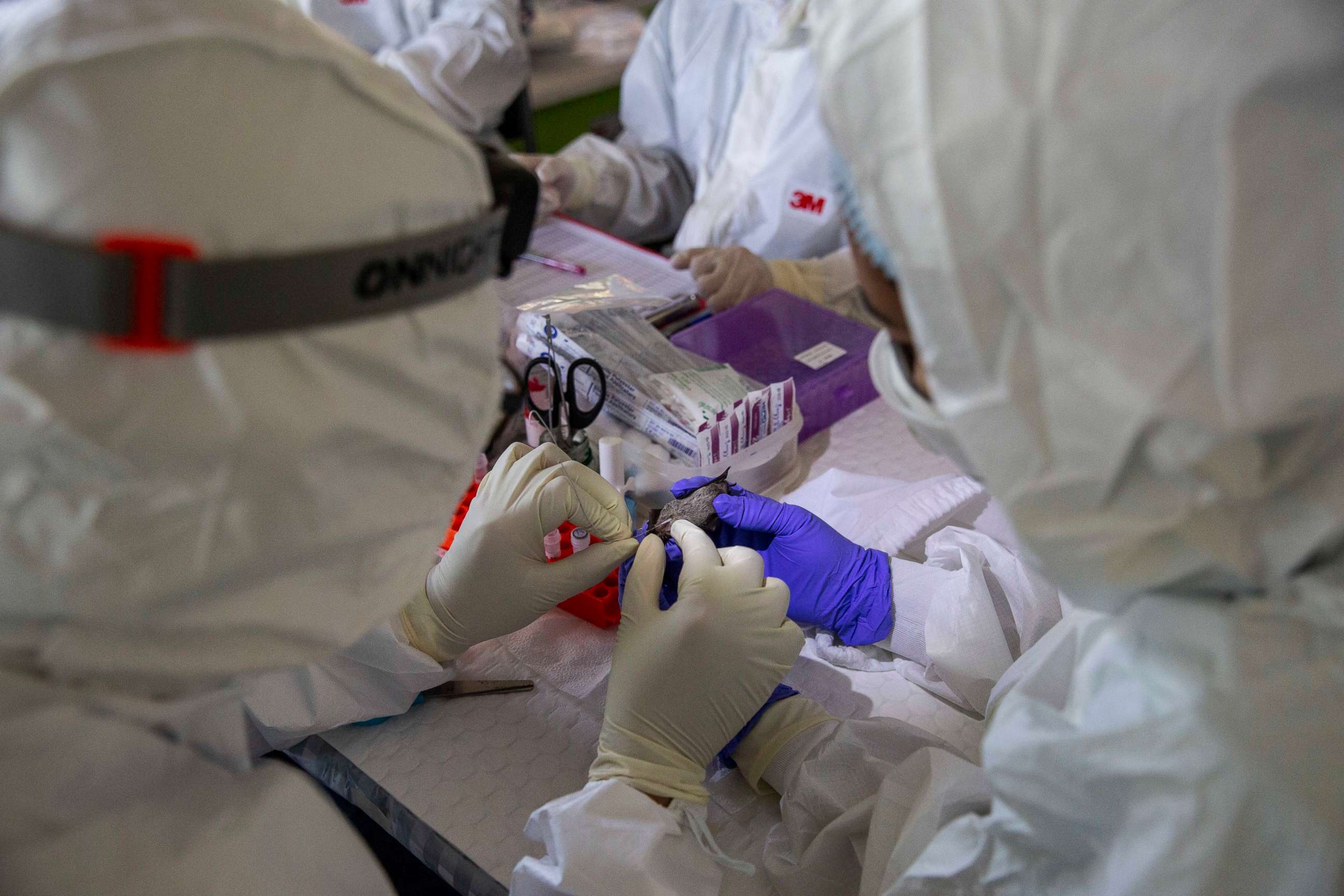

Nine months into the global pandemic, scientists are still piecing together the mystery of the first crossover event, in which the coronavirus moved from bats to an intermediary animal, and eventually, to humans.

By comparing the patterns of mutations from the new coronavirus to other known viruses, researchers have been able to create an evolutionary history of the related viruses, and found a "single lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic." Surprisingly, they also found that the closest known ancestor of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has actually been living in bats for 40-70 years.

"While the new virus looks like coronaviruses that circulate naturally, it's unique in ways we didn't know about before the pandemic," said Dr. David Robertson, head of viral genomics and bioinformatics at the Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation at the University of Glasgow.

Robertson and his team study how coronaviruses recombine in identifiable ways, which allows them to study the evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Scientists still aren't sure what happened in between bats and humans, but they say it's likely the virus circulated for a while in a pangolin or another intermediary animal.

Despite some lingering questions about how and when the virus made its journey from bats to humans, Robertson said his research on the virus's genetic code proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that the virus came from nature, and that by studying the virus's origin, we can better prepare for the next pandemic.

According to their recent study, which is awaiting peer review, humans are almost the perfect hosts for SARS-CoV-2, as the virus has "apparently required no significant adaptation to humans since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic." As a result, the virus naturally evolved in bats and was almost immediately ready to be spread through human contact.

"As part of our understanding of how this virus emerged, where it emerged from and what took place, this study adds an important component to an evolving story," said Dr. John Brownstein, the chief innovation officer at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor.

"It shows it wasn't some big recombination of viruses that led to the pandemic -- it was actually a virus that had been circulating for a long while in bat populations that had properties that were conducive to human infection," he added.

"If it had been made in a lab, it would have looked like viruses we already knew about, more closely related to the SARS virus," he said.

Yet, conspiracy theories about the virus's origins persist. In the most recent example, an anti-Chinese government group linked to Steve Bannon published a swiftly rebuked paper alleging that "laboratory manipulation is part of the history of SARS-CoV-2." The paper makes a number of bold accusations, including that the virus was made in a lab controlled by the Chinese government. Virology experts widely agree, however, that none of the authors' claims can be supported.

"There is nothing in this document that supports the idea that it is man-made," said Stanley Perlman, M.D., Ph. D., a professor at the department of microbiology and immunology, and the department of pediatrics at the University of Iowa.

"In addition, no one would have known how to construct a pathogenic virus, and too little is known to predict pathogenicity," Perlman said.

"There is a great deal of experimental support, from multiple groups, on the natural origin of SARS-CoV-2," said Vincent Racaniello, Ph. D., a Higgins professor in the department of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Animal-to-human transmission of viruses has been responsible for many diseases, like the bubonic plague or the West Nile virus, and have caused other recent outbreaks, such as the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak and the global HIV/AIDS pandemic.

"This is a story that you have over and over again, where you have these viruses circulating in animal populations, and there is some moment where these viruses were able to infect someone," said Brownstein.

To prevent a future pandemic, scientists say our best bet is to better understand the link between animal populations and human populations.

"Landscape, fragmentation, climate change, transportation or illegal wildlife trade: All these factors are creating new interfaces for humans and animals. That probably was part of the reason for this pandemic," said Brownstein.

Having those scientific conversations will likely be the key to stopping a future pandemic -- next time, before it starts.

Dr. Leah Croll and Sony Salzman contributed to this report.