FDA approves new closure device for heart defect in premature babies

One out of 10 of all babies are born premature.

One in 10 babies are born premature and Irie Felkner and her twin brother, Judah Felkner, were two of them.

Born 13 weeks prematurely, they were unable to breathe on their own after birth and had to be placed on ventilators. They were transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit at Nationwide Children’s in Columbus, Ohio. Judah was able to breathe on his own and come off the ventilator after a week. But Irie could not.

"She had a hole in [the artery coming off] her heart, a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)," the twins' mother, Crissa Felkner, said. "Doctors tried to take her off of the ventilator nine times but she was unable to sustain herself since the PDA was there. A machine was keeping her alive."

What sounds like a mother’s worst nightmare is actually a reality for many families. The U.S. is sixth on the list of countries with the most preterm births. India, China and Nigeria top the list.

Of the 15 million premature babies that are born each year, 1 million of them die of complications from being premature, according to the World Health Organization. One of these deadly complications is a PDA. On Monday, the FDA approved the groundbreaking use of a minimally-invasive device to close the hole and treat PDA in premature babies.

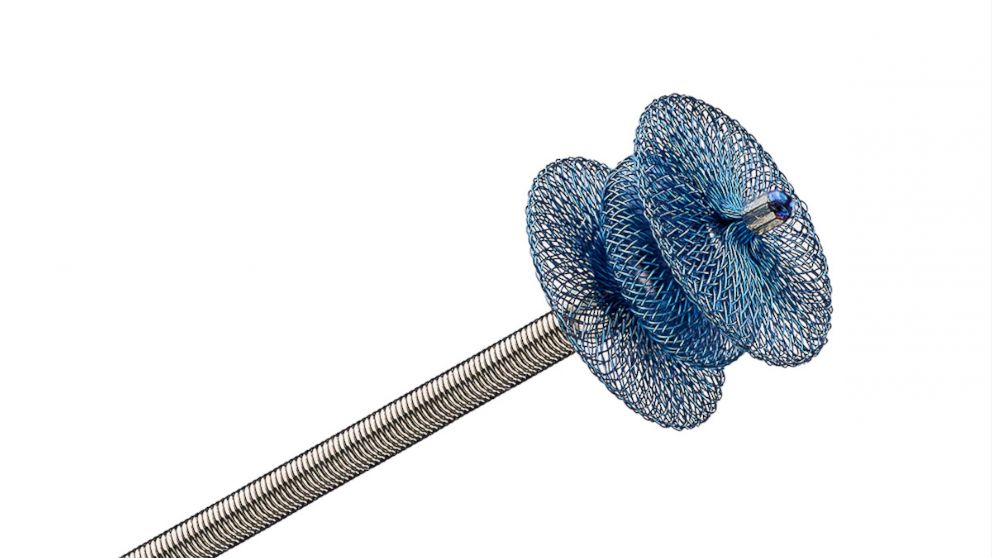

This device, called the Amplatzer Piccolo Occluder, was used to treat the PDA in Irie. It is a small self-expanding mesh device (smaller than a pea) that is inserted through a tiny incision in the leg. It goes into the arteries of the body through a minimally-invasive catheter, enters the PDA and seals the hole. “It is based on similar technology that Abbott has used for the past 20 years to perform minimally invasive procedures but that technology was previously only available for larger-sized babies,” said a spokesperson for Abbott, the company behind the research and manufacture of the device.

“We were given four options, one of them being the Piccolo Occluder, which is what we eventually went with,” Felkner explained. “The other options were waiting and seeing if the hole would close on its own, medications to try to close the hole (but those are not always effective and have side effects), or open heart surgery.”The Piccolo Occluder was not FDA approved at that time which did concern the Felkners. It was also the reason they waited a few days before deciding to go ahead with the procedure.

After about a week of waiting and watching, a repeat echocardiogram, or ultrasound, of her heart showed that it had enlarged and that her condition was getting worse. She was not a candidate for surgery since she still only weighed 2 pounds. Suddenly, the procedure with the Piccolo Occluder turned out to be Irie’s only option for survival.

“She wasn’t getting better so we had to take a leap of faith that this device would work,” Felkner said.

What is a PDA?

The ductus arteriosus (DA) is a normal small artery that all babies have before they’re born that connects the two bigger and main arteries of the body, the aorta and the pulmonary artery. Its purpose is to shunt blood away from the lungs of the fetus and to the aorta since at that stage the fetus is getting its oxygen supply through the umbilical cord, not the lungs. Right after birth when babies are able to take their first breath, their lungs expand and the DA is no longer needed and closes on its own within the first five days of life. But in some babies, usually ones who are premature, the DA doesn’t close like it normally should and remains open.

This heart defect, called a PDA, can cause a decrease in the amount of oxygen in the blood that is delivered to the body's organs. Sometimes blood can flow in the reverse direction through this open defect, or “hole,” and into the lungs, causing fluid in the lungs and heart failure in babies, which is what happened to Irie.

From clinical trial to FDA approval

“Three days after she had this procedure done, she was off of the breathing machine. This minimally-invasive procedure saved my daughter’s life and did not even leave a single scar. She has no limitations now. She is a normal toddler and can do anything her brother can,” Felkner said.

Before the approval issued today, there was no minimally-invasive option to correct this heart defect urgently in babies the size of Irie. They would either have to grow bigger in order to get a minimally-invasive device or have an invasive open heart surgery that had a high risk of complications, including death itself.

Irie was treated as a part of the U.S. clinical trial called the ADO II AS, which enrolled 50 premature babies over the age of three days at eight centers across the U.S. Its results combined with that of a continued access protocol involving 150 more patients supported its safety and efficacy which led to the FDA approval.

As the rates of prematurity in the country continue to increase, the addition of this modern technology is a big step forward in treating some of the smallest -- and most vulnerable -- population of all.

Azka Afzal, MD, is an internal medicine resident physician in Houston and is a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.