Without federal 'blueprint,' states become hodgepodge for coronavirus testing

Expert: To dramatically scale up, US needs "national-level" strategy.

They were the first coronavirus antibody tests authorized by the government, and though the 100,000 units were a tiny fraction of what would be needed for hard-hit New York City, they were a start -- if they could make it to the U.S.

Instead, the 100,000 kits ordered by the medical firm Cellex took a full month to make their way from China to American shores and to front line workers in New York, in a frustrating odyssey in which Cellex officers said the U.S. government offered little guidance or assistance.

The story of Cellex and its shipment of antibody tests has a good ending. But it also illustrates part of the confusion, delays and complexities of acquiring, distributing and administering virus and antibody tests to a nation of more than 328 million without a national testing architecture.

Absent one unified plan, states, cities and private industry have been left to figure out which tests should be used, who should get them and what the results might mean -- leaving a patchwork of policies from state to state and even city to city.

“We urgently need a national plan to close that gap,” Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security told a congressional hearing Wednesday. “Scaling to the first 1 million tests per week, though hard-fought, was largely about bringing to bear existing resources. Getting to triple that, or 10 times that, will require national-level strategic planning and innovation."

Senate Democrats this week renewed calls for President Donald Trump to take a more aggressive role in leading the nation on the testing front.

“We are deeply troubled by the lack of detail and strategy in your testing blueprint, and we fundamentally reject the notion that the federal government bears this little responsibility in increasing testing capacity,” 42 Democratic members of the U.S. Senate wrote to Trump Tuesday. “Our public health, government, and business leaders need information about who has COVID-19, who needs to be isolated or quarantined, and who may be immune due to previous infection.

“The only way to get that information is testing: widespread, fast, free testing — and the only way to accomplish testing on the scale needed is a nationally coordinated effort,” the letter said.

For his part, though, Trump said he sees no reason to change the course he set in which the onus is on the states.

In an exclusive interview Tuesday with ABC News' "World News Tonight" anchor David Muir, Trump repeated his mantra that “testing… has been a tremendous success.”

“We've done more testing than any other country, by far,” Trump said, referring to the total number of tests administered, rather than the per capita rate. “Very importantly, we have the best testing. We have the best testing.”

A few other nations with smaller populations, like Denmark, New Zealand and hard-hit Italy, have reportedly tested more people per capita than the U.S., though the rate of testing in the U.S. has risen in recent weeks.

A senior official with the Federal Emergency Management Agency told ABC News this week that FEMA along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Health and Human Services are all supposed to be preparing to announce a major testing initiative next week. But the official said their agency's leadership was still unclear on the details.

Cellex and 100,000 tests stuck in China

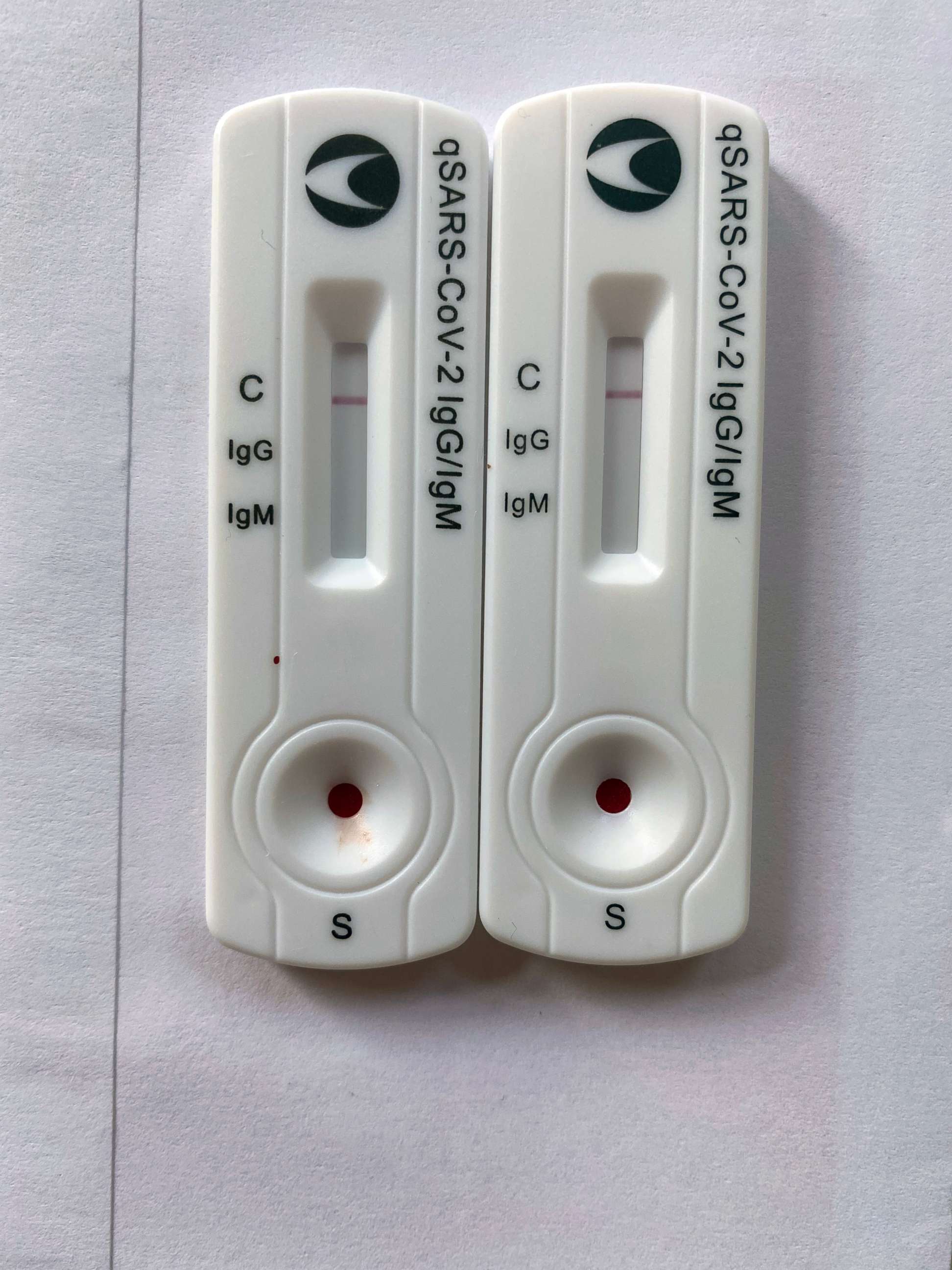

When officials talk about testing, they are generally referring both to antibody blood tests, like Cellex's, that are designed to show whether a person has been exposed to coronavirus in the past, and live virus testing, which indicates whether someone has the COVID-19 infection at the time of the test. Both would be used to help public health agencies determine who is at risk from exposure as public spaces and businesses start to be repopulated, experts say.

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

The live virus testing was the first to be widely used in the U.S., though after its own costly delays. The FDA issued the first emergency-use authorization for an antibody test for coronavirus on April 1.

That much sought-after nod went to the kit produced by Cellex, a medical-diagnostics company based in North Carolina’s Research Triangle. Soon after the announcement, arrangements were made to get an order of 100,000 test kits earmarked for New York City’s Health & Hospitals agency, which would administer the tests to first responders.

But the Cellex kits, which were manufactured in China, got caught up in Chinese export restrictions imposed to ensure the supplies were safe and to help that country wage its own battle against COVID-19.

For weeks, it was an around-the-clock mission to try to get the approvals needed for the crates and crates of antibody test kits to take off for America, according to Cellex officials. As the negotiations dragged on, pleas kept growing more insistent from New York leaders and officials around the U.S. waiting for antibody tests.

On April 16, officials from the U.S. Health and Human Services Department reached out to the company to ask where the tests were. Cellex executives said they held one conference call with HHS staff and explained how they couldn’t get the kits out of China.

“We have those tests, but they are in China so feel free to pick them up,” Jinjie Hu, chief operating officer of Cellex, said of her conversations with HHS. “They are in our manufacturing facility in Suzhou, about 50 miles from Shanghai airport. They are ready in China if you want to go pick them up, go ahead.”

Then nothing.

"They didn’t reach out again,” Hu said. “They didn’t do any follow-up. They got the information to generate a spread sheet, so that was probably the purpose. But no action. We didn’t get any help from the government.”

HHS did not respond to requests seeking comment for this report.

Instead, Cellex enlisted the help of at least 30 people – among them Chinese diplomats, influential private citizens and American officials, executives said. The Chinese government approval came through April 27, but even then roadblocks still didn’t stop.

"This is life, just in fiction,” Hu told ABC News. “It’s like we are living in fiction during this period. It’s a roller coaster we’ve been through. It's unbelievable."

It took seven hours to truck the shipment to the airport, but that was only after getting done with three days of additional back-and-forth with Chinese customs personnel. At the same time, Cellex had to figure out how best to transport the NYC-bound tests along with another 400,000 kits destined for other destinations in the U.S.

Given the choice between private jets and commercial cargo planes, Cellex chose both -- just to hedge its bets.

“It was 24/7 in both sides of the Pacific Ocean in the last 30 days,” Li said. “The tests arrived to the US exactly one month after FDA granted Cellex the first rapid COVID-19 serological test” authorization.

Once stateside, a question of who gets what

In the time since that first FDA authorization, leaders at all levels of government have made clear widespread testing would enable them to loosen the restrictions that have left much of America locked down since March.

“There is a lot of emphasis on testing,” said the senior FEMA official. “The premise is you want to figure out who is sick so you can isolate the people who have the virus and know who had the virus and people that are safe and so on." The federal government is "supposed to be coming out to show lines of responsibility or lines of effort and who is responsible for what.”

But for weeks now many states, and individual cities have had to ration their testing for the most at-risk groups, a policy supported by general guidance offered by the White House and the CDC.

In the case of the Cellex tests, most of those went to first-responders in New York who are on the front lines of the fight against the virus.

Like New York, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan looked abroad for help finding test kits and eventually received 500,000 directly from South Korea. He put his state's rationing policy bluntly when he said that the state is "not just going to send them off to people."

Instead, the state is reserving them to prioritize expanding its testing capabilities on “high-priority outbreaks and clusters,” including health care workers, first responders, nursing homes and poultry processing facilities, Hogan said.

Maryland’s state public labs earlier last month also secured an additional 40,000 tests, including 30,000 kits compatible with the Abbott m2000 testing machines, and the state entered into an agreement with Abbott Labs to acquire a substantial number of antibody tests.

Overall, testing capacity and policy between the states has been a hodgepodge, with some moving toward easing stay-home restrictions before being able to prove through testing that infection rates are actually on the decline.

As tests have become more readily accessible in some places and researchers learn more about how the virus spreads, some states are expanding their protocols as they see fit to include essential workers, regardless of symptoms, and those in communal-living spaces, like prisons or nursing homes.

The CDC has been providing guidance on how tests should be prioritized, but the states have wide latitude to act on their own. For example, the federal agency recently revised its standards to rank nursing home residents as a top priority for tests because they've shown to be especially vulnerable to the virus, but a survey by ABC News found that some states have not yet implemented universal testing for nursing home residents.

Among those that have, however, are Tennessee, West Virginia and Maryland -- now requiring all nursing home residents and staff to be tested.

Tennessee also announced it would begin “mass” testing of inmates in state prisons, another hot spot for outbreaks.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy announced last week that the state too will start universal testing for prison inmates and staff as early as the end of next week thanks to a partnership with Rutgers University.

All New Jersey public transportation system employees will soon have access to testing at the American Dream site at the Meadowlands, which has been serving our first responders and frontline health care workers, officials said.

California, which was already prioritizing prison population testing, updated its testing priority guideline last Friday to include asymptomatic health care workers as well as symptomatic and asymptomatic essential workers such as utility workers, grocery store workers, food supply workers and other public employees, in its priority screening groups.

Los Angeles is going even farther, with the mayor announcing last week that the city will offer free coronavirus tests to all residents, regardless of symptoms.

The state of California has been running an upward of 30,000 tests per day in recent days, and Gov. Gavin Newsom recently announced that the state is working to increase its daily testing capacity to a minimum of 60,000 to 80,000 in coming weeks to “make sure all Californians are tested.”

Michigan, too, has expanded its testing criteria in recent weeks to include individuals with milder symptoms and all essential workers still reporting to work in person, whether they are symptomatic or not.

“This means that anyone with symptoms can get a test as well as any individual regularly interacting with others outside their household, as long as the testing location has the supplies,” said Dr. Joneigh Khaldun, chief medical executive and chief deputy for health in Michigan.

But Michigan continues to struggle with obtaining enough swabs and testing kits, Michigan health department spokesperson Lynn Sufton told ABC News. The state currently has a daily capacity of about 16,000 tests.

Praise for some states, while others try to catch up

As the example of Michigan indicates, how widespread the tests can be conducted is a function of how many tests, and test equipment, are available in the first place, and states across the country are racing to ramp up their capacity.

Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, told a conference call of state governors Monday that six states are testing more than 4% of their populations, which is "really quite impressive,” according to an audio recording on the call, obtained by ABC News. Birx did not specify the states she was talking about.

Birx also said one state went from testing less than 2% to 5% in a matter of weeks and said a little more than 2% of the total national population has been tested.

However, some states acknowledge they are still much behind.

In an interview with The Alabama Political Report last week, Scott Harris, an official at the Alabama Department of Public Health, estimated just 1,000 people were being tested per day in the state.

“The idea of 50,000 tests a week actually is doable, based on what people are reporting to us right now,” Harris said in the interview. “There’s enough capacity available in all of these labs to handle that volume. But practically speaking, we’re nowhere near that.”

Alabama, like many other states across the country, has turned to the private sector to assist with expansion. Alabama public labs have the ability to perform just 350 tests per day “when everything is perfect,” Harris said.

“I really think that one big perception issue around testing is that the feds have made it clear that state public health labs are not going to be the ones doing the bulk of testing, even when we would like to be,” Harris continued. “They’ve made it very clear that we need to be augmenting the private capacity. That’s what we’re trying to do, and we’re trying to recruit people to do that.”

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, who faced a backlash for taking aggressive and early measures to reopen his state two weeks ago, this week praised partnerships with universities and private companies for helping the state increase its testing by significant margins.

In a column that appeared in the Augusta Chronicle Sunday, Kemp wrote that “testing was our Achilles’ heel as we fought COVID-19.

“We’re really starting to ramp up our testing,” Kemp said on the Monday call with governors. “We did 31% of our testing total in the last seven days.”

On the call with Birx there were few complaints, though governors made clear the current system has kinks -- whether it was getting help from the federal government or from private companies that some states have come to rely on.

Gov. Jared Polis of Colorado, where many communities have already opened up ahead of other parts of the state, said his state still needs help getting supplies from manufacturers and distributors.

“We really appreciate the partnership of the federal government,” Polis said. “We don't yet have that from our private sector partners, the ones we've connected with.”

Still, while the details of the federal initiative planned for next week remain unclear, state and local officials continue to voice concerns about the shortages in swabs, reagents and other materials needed if they are going to be able to ramp up testing.

In explaining the situation to Congress this week, John Hopkins’ Rivers said there needs to be a back-to-the-basics approach to something as crucial as testing.

"We should start by understanding, from start to finish, what resources and components are involved in the testing pipeline,” she said, listing the components needed. “Swabs, reagents, test kits, (personal protective equipment), have all intermittently been implicated in shortages.

"Next, national leaders should map out in great detail, the current and expected capacities for each of these elements: what national capacities can we expect at the end of May and June and August? Where are the bottlenecks? What untapped resources could we draw from? How will we get from where we are to where we want to be?” she said.

Rivers didn’t hide her frustration.

“If this work has been done, I have not seen it and I fear that neither have the governors and other state and local leaders who are having to make decisions about how and when to reopen,” she said. “The Federal government should take on this strategically important assessment and planning process to increase testing capacity in the U.S. and should make the results publicly available."

ABC News’ Katherine Faulders, Olivia Rubin, Ali Pecorin, Soorin Kim and Ben Siegel contributed to this report.