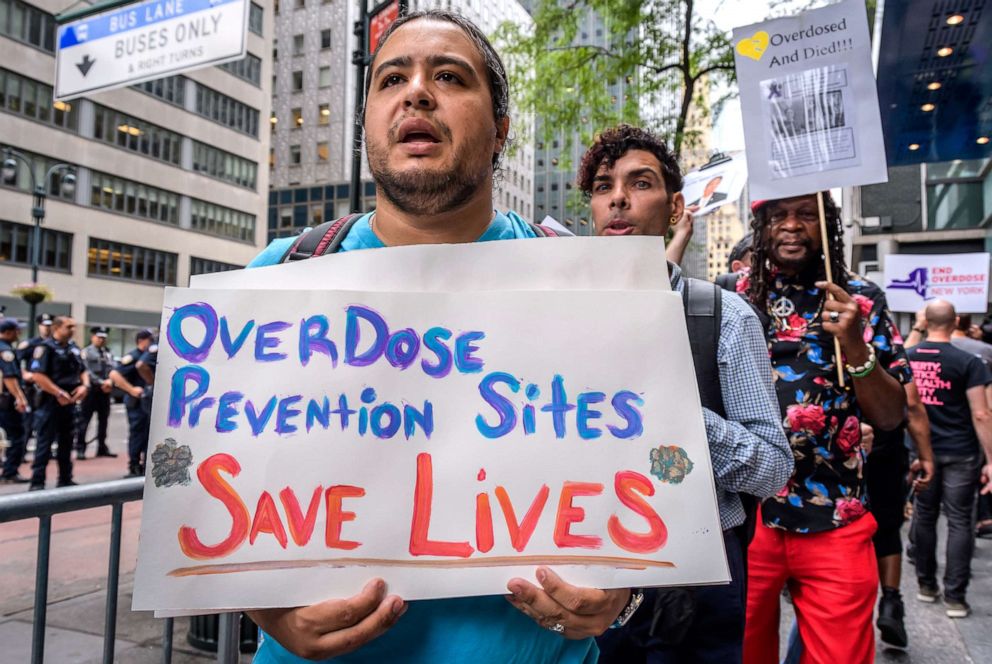

Why opioid overdose prevention programs work as NYC leads nation with 1st center

The center has already intervened in 134 overdoses that could have been fatal.

It's been two months since New York City opened the first-ever overdose prevention center (OPC) in the United States, and public health experts said the clinic is already saving lives.

OPCs are a form of harm reduction, which is a set of strategies to minimize the negative effects and consequences linked to drug use, and "keeping people who use drugs alive and as healthy as possible," according to the U.S. government's Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In this case, OPCs are place where people can use drugs in a setting with nurses or other clinical staff members present and who can help avert fatal overdoses.

As of Feb. 8, the center has served nearly 700 New Yorkers and intervened in 134 overdoses, according to OnPoint NYC, which staffs the site.

Critics said OPCs are places that allow people to use drugs without attempting to help them get clean and that state and local governments are forced to pay for materials including crack pipes and meth pipes to feed people's addictions.

But anti-drug war advocates and other experts said these centers are vital in reducing opioid deaths, destigmatizing drug misuse and connecting people to resources for their substance abuse -- all in a safe environment.

"We are now creating safe spaces for people to use that are not -- they're no longer feeling criminalized," Emily Kaltenbach, the senior director of criminal legal & policing reform at the Drug Policy Alliance, a non-profit seeking to reduce the harms of drug use, told ABC News. "People can come and feel safe to use. They're no longer using in alleys or by themselves."

She said OPCs prevent drug users from other harmful behaviors that could increase their risk of death, such as taking contaminated drugs or injecting with dirty or shared syringes. Staff can also administer naloxone, a medication to reverse overdoses.

"In these centers, there's immediate access to life-saving, overdose prevention interventions there," Kaltenbach said. "People are not sharing syringes, for example. So, the prevention of the spread of diseases by reducing HIV and hepatitis C is huge."

OPCs also traditionally have connections to services such as mental health therapy, drug treatment programs and housing.

"This is a step forward in making, in really treating drug use as a health issue and not as a criminal issue," Kaltenbach added.

It comes as the nation hit its most sobering milestone in the ongoing opioid epidemic.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 100,000 Americans died of drug overdoses between May 2020 and April 2021.

This means roughly 1,923 people died of drug overdoses every week.

Of the total deaths, about 75,000 were due to opioids, including oxycodone and hydrocodone, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl -- most of which is trafficked into the U.S. through China -- according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

The problem is widespread across the United States, including in New York City, according to Dr. Dave Chokshi, commissioner of the city's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene:

"In the year 2020, over 2,000 New Yorkers died of an overdose," he told ABC News. "That means every four hours, a New Yorker died of an overdose and the total number is more than deaths due to homicides, suicides and motor vehicle crashes combined. So this is a five-alarm fire in public health."

There are currently two sites in the city, one each in the Manhattan neighborhoods of East Harlem and Washington Heights, and are staffed by OnPoint NYC, which merged from non-profits New York Harm Reduction Educators and Washington Heights Corner Project.

"We are humanizing and giving hope to people that far too often society sees as disposable and defines them by their mistakes," Sam Rivers, Executive Director of OnPoint NYC, told ABC News in a statement.

OPCs are not without their critics, which argue the centers enable drug users, who will just die of overdoses in other settings.

Dr. David Murray, co-director for the Center for Substance Abuse Policy Research at the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C., said illicit drug users will take drugs "beyond the facility borders."

"Not uncommonly, drug users inject multiple times a day, and … the consumption site simply becomes one more place in which to consume drugs, providing for only a fraction of an addict's aggregate exposure," he wrote in a column for the Hudson Institute in August 2020.

But Kaltenbach and others say OPCs reduce the amount and frequency that people use drugs and reduce public disorder and public injection while increasing public safety.

At Insite Supervised Injection Site, the first overdose prevention facility in North America, which began operating in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, in 2003, one study found that the fatal overdose rate in the area around the site fell by 35% after it opened.

Additionally, the programs help increase entry into substance use disorder treatment programs, according to Kallenach. Another study found that more than half of users at Insite entered addiction treatment within two years.

There are currently 120 OPCs operating in ten countries around the world, and the Drug Policy Alliance says there has not been a single overdose fatality at any OPC.

"No one is claiming that they are a silver bullet for all of what we're seeing with respect to the overdose crisis or the broader set of issues surrounding drug use," Chokshi said. "For that, it involves investments like the ones that we have made in New York City around lowering barriers to accessing treatment … investing in syringe service programs so that people have access, not just to safe and clean supplies, but also all of the wraparound services, whether it's housing or job placement, or food and medical care, basic human needs, that are provided in those programs."