Tracking breakthrough cases key to pandemic response, experts say

Waning immunity is a "real phenomenon," one health official said.

Waning immunity has become a focal point in the pandemic.

COVID-19 cases among those fully vaccinated against the virus have been cited by several state public health officials as partly responsible for recent surges in cases. They were also behind the push for boosters for all adults ahead of federal authorization -- and the reason for boosting in the first place.

"There's no doubt that immunity wanes. It wanes in everyone. It's more dangerous in the elderly, but it's across all age groups," Dr. Anthony Fauci, the White House chief medical adviser, said earlier this month, citing data from Israel and the U.K., where more people were vaccinated sooner and both began to first document waning immunity.

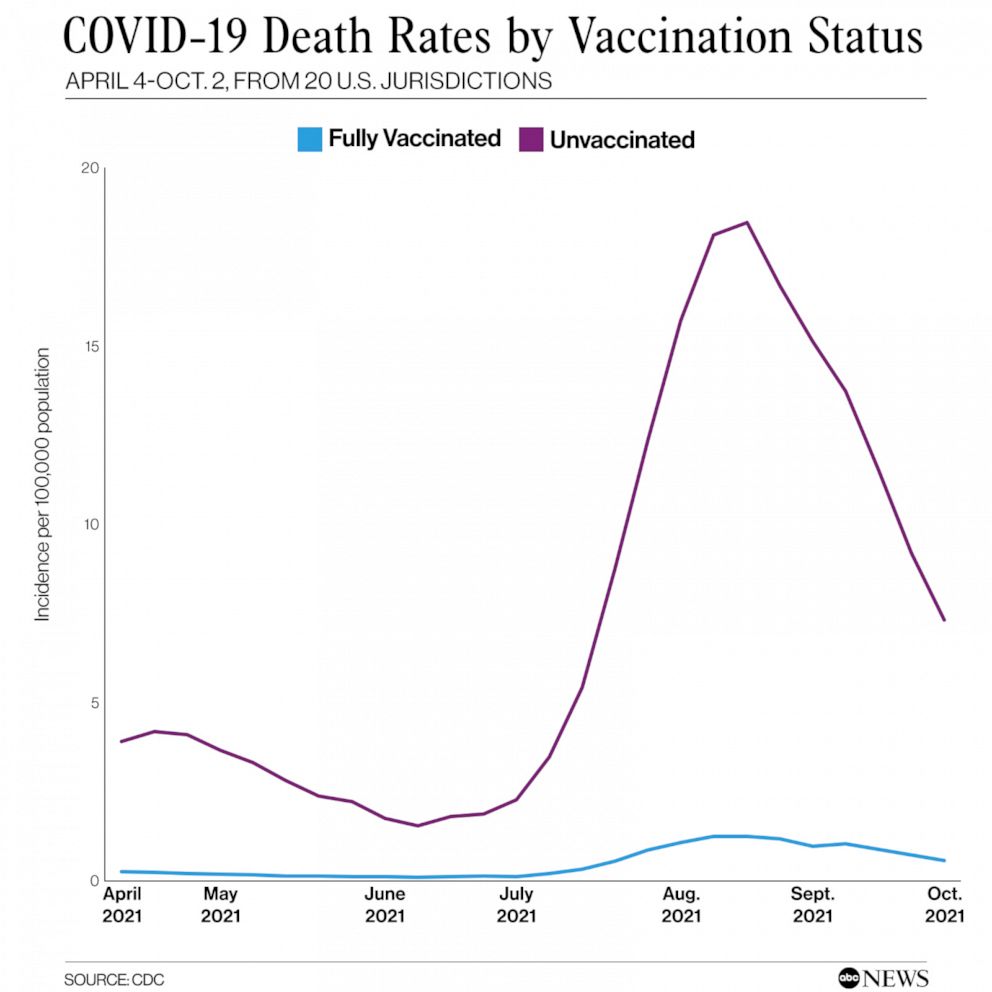

Experts stress that the vaccines remain highly effective against severe COVID-19 illness, and vaccinated people continue to share a lower burden of hospitalizations and deaths among COVID-19 patients as cases and hospitalizations are on the rise again in the U.S.

The data is limited and hard to track, though knowing more about breakthrough infections is an important tool in responding to the pandemic, experts say.

Vaccinated COVID-19 cases always expected

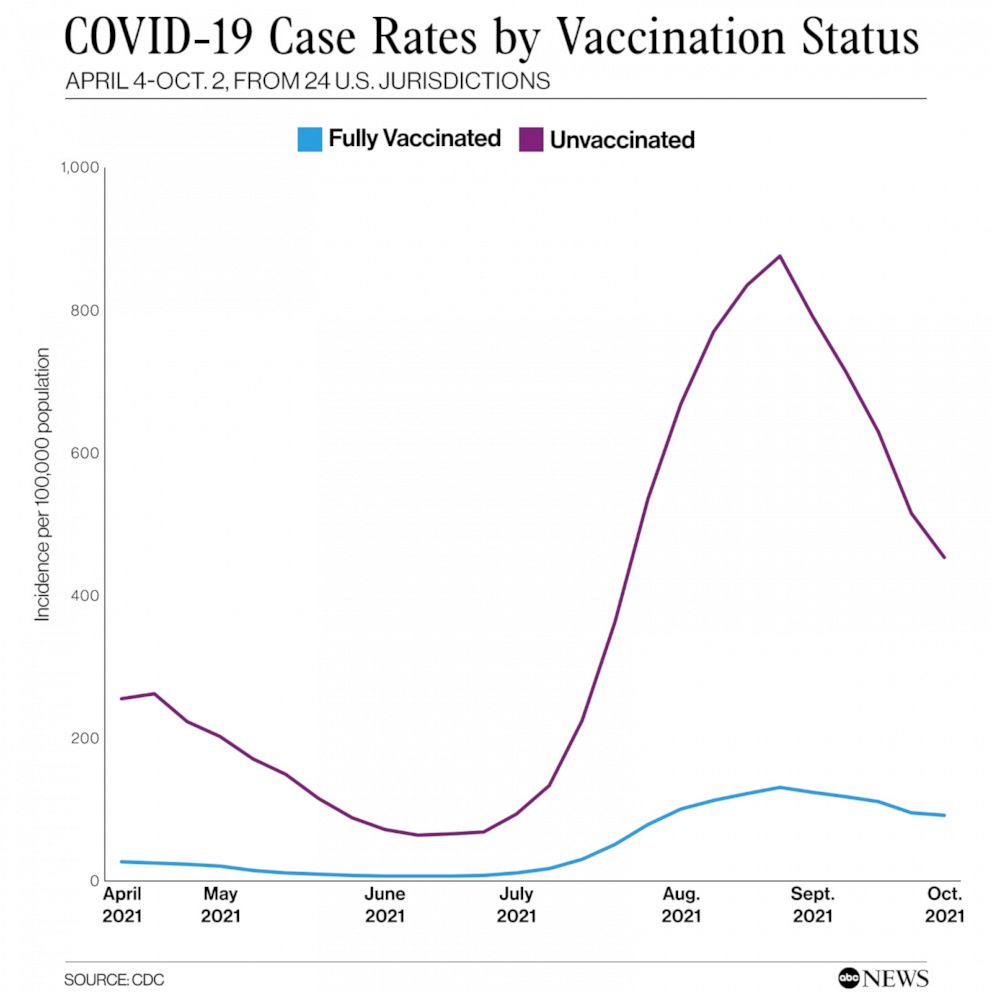

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking COVID-19 case rates by vaccination status since April shows a relatively flat line for vaccinated people that started to slope up in July -- though not nearly as steeply as case rates among unvaccinated people.

Breakthrough cases were always expected -- and expected to go up over time, Dr. David Dowdy, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told ABC News.

"The reason is, first of all, more people are vaccinated," he said. "The more people who are vaccinated relative to being unvaccinated, the more likely it is that a person who gets sick is going to be vaccinated, just by pure numbers."

As the number of unvaccinated people who get COVID-19 also continues to increase, it may look like more cases are breakthrough when comparing cases by vaccination status, he said.

Another reason for increasing cases is due to waning immunity, Dowdy said.

"There is this waning immunity to getting sick -- not getting really sick, but getting infected, getting that initial illness," he said. "And so over time, people have a little bit less protection against that."

No vaccine provides 100% protection, though they are intended to help prevent you from getting very sick if infected. The initial immune system response is ramped up for several months after vaccination, though those antibodies "die out over time," leaving behind a "memory response" to help protect against severe infection, Dowdy said.

When that happens varies from person to person depending on factors like age and health. In general, Pfizer's data on its COVID-19 vaccine shows a decrease from an initial 96% efficacy to 83.7% efficacy after four months. A study by Kaiser Permanente Southern California found that efficacy against infections declined from 88% during the first month after full vaccination to 47% after five months.

A booster dose brings the immune response back up to a "robust" level seen one month after two doses, Pfizer found.

Booster doses are now eligible for all adults as COVID-19 transmission remains high in many parts of the country, "creating additional challenges and exposures for those who are vaccinated," said Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor.

"Just based on probability, with enough exposures to the virus, you will have breakthrough infections," he said. "But those breakthrough infections doesn't mean the vaccines aren't working -- it just means over time, the probability of getting infected through an exposure to the virus, that probability increases."

"Despite that, we know that the vast majority of those breakthrough infections are mild, especially much milder than they would be if someone wasn't previously vaccinated, and they don't lead to anywhere near the same levels of severe illness and death," he said.

In September, unvaccinated individuals had a 5.8 times greater risk of testing positive for COVID-19, and a 14 times greater risk of dying from it, as compared to vaccinated individuals, according to CDC data.

Waning immunity a 'real phenomenon'

Although the vast majority of COVID-19 infections and severe hospitalizations are among the unvaccinated, cases in vaccinated people do appear to be on the rise due to waning immunity, according to health officials.

In New Mexico, health officials have cited waning immunity as one of the reasons behind a recent surge in COVID-19 cases. The most recent state data shows that nearly 29% of cases and 21% of hospitalizations from Oct. 18 to Nov. 15 were among vaccinated people.

Similarly, health officials in Vermont, the most vaccinated state by population, have pointed to waning immunity as partly behind its worst COVID-19 surge yet.

"Waning of vaccine immunity is a real phenomenon," Dr. Mark Levine, commissioner of the Vermont Department of Health, said during a press briefing in mid-November.

Vermont also leads the nation in administering booster doses to people ages 65 and up. This week, Levine told reporters that the health department's data reaffirms that "booster shots are working." Case rates among those ages 65 and up in the state make up only 10-12% of COVID-19 cases, he said. The most recent state data also shows case rates among that population have decreased 14% week-over-week while increasing for every other age group.

"The need for a booster does not mean the COVID-19 vaccines have failed to do their job," he said. "They are highly protective against the worst effects of COVID. But the protection we get from a vaccine can start to wear off over time."

"For COVID-19, booster shots are especially important for those at higher risk who got vaccinated early on, like the majority of Vermonters who fall into this category and were vaccinated very early in this year. And at a time when COVID-19 transmission is high, when we're indoors more and getting together over the holidays, boosters really do benefit us all," he added.

Challenges in tracking breakthrough infections

Tracking breakthrough cases can be challenging, and most efforts likely represent an undercount due to a lack of testing of asymptomatic cases and reporting of at-home test results, according to The Pandemic Tracking Collective, a group of former members of The Covid Tracking Project that offers data solutions for tracking the pandemic. Breakthrough data is also not standardized across states, and not all report breakthrough cases, hospitalizations and deaths, the group said in a recent report.

In this patchwork of breakthrough infection-related collection, 36 U.S. jurisdictions report cases, 34 report hospitalizations and 37 report deaths, according to The Pandemic Tracking Collective report. At the time of its report, the CDC tracked cases for 16 jurisdictions and deaths for 15 jurisdictions by vaccination status, updated monthly. That has since increased to 24 and 20 jurisdictions, respectively, in the tracker's latest update this week. The CDC also reports on hospitalizations by vaccination status in 14 states.

"Now we have data on COVID-19 case counts and hospitalizations at our fingertips. What we lack is nuanced and detailed information on vaccine breakthroughs, which will be key to ending this pandemic," Jessica Malaty Rivera, science communication lead at The Pandemic Tracking Collective, said in a statement.

Breakthrough infections can help scientists better understand declining vaccine efficacy and detect new variants, the group said. Having better data can also help enact effective policies, Brownstein said.

"It's very hard to make policy decisions with imperfect data," he said. "Being able to understand the extent to which we're seeing breakthrough infections and their severity is important to make decisions around things like boosters, decisions around requirements for those who've been exposed or infected."

"When you have that kind of data, it can tell you very clearly what the burden of disease is in vaccinated people," he continued. "But without that, we have very limited information. So I think that is one of the real deficiencies in public health surveillance, is a lack of clarity on the impact of this virus among vaccinated and unvaccinated."

For Dowdy, data on breakthrough cases can provide "valuable information as we think about how we can best fight this pandemic," including the duration and level of protection that the vaccines are providing. Though he warned against reading the data as "trying to split the population in two."

"At the end of the day, we're all in this together, vaccinated or unvaccinated," he said.

ABC News' Arielle Mitropoulos contributed to this report.