Long-lost Yiddish songs tell first-hand stories of Soviet Jews during the Second World War

Long-lost Yiddish songs tell stories of Soviet Jews during the Second World War.

Sophie Milman’s grandmother was in her early teens when she fled from Ukraine to Kazakhstan with her mother and younger sister at the start of the Second World War.

As Jewish men, including Milman's great-grandfather, joined the Red Army to avenge the Holocaust, hundreds of women and children fled for fear of persecution by Hitler’s sympathizers in Ukraine, the then-epicenter of Jewish life in the Soviet Union.

Living minimally in a mud hut, her grandmother completed her education at home on her own -- and in the absence of her soldier father who was never heard from again -- "manned-up" to parent her own devastated mother, Milman said.

Milman, an award-winning jazz vocalist who was born in Russia and reared in Israel before the family moved to Canada, said University of Toronto's professor Anna Shternshis approached her around three years ago about singing a few Yiddish songs from the Soviet-era she was hoping to revive. One of the songs described the journey of Jews who fled the forests and seas of Ukraine to rebuild their lives in the windy mountains of Kazakhstan.

"[The] howling winds are the voices of the families they left behind, the people perishing in mass graves or camps," Milman told ABC News. "It’s a dark song filled with fear and anxiety and change and newness and a person’s mind racing and trying to make sense of life that went from normal to completely abnormal literally overnight."

Milman learnt phonetic Yiddish and said that she put herself in the shoes of her then-teenage grandmother to emotionally connect with the song.

"It helps me understand my grandparents’ experience better," she said.

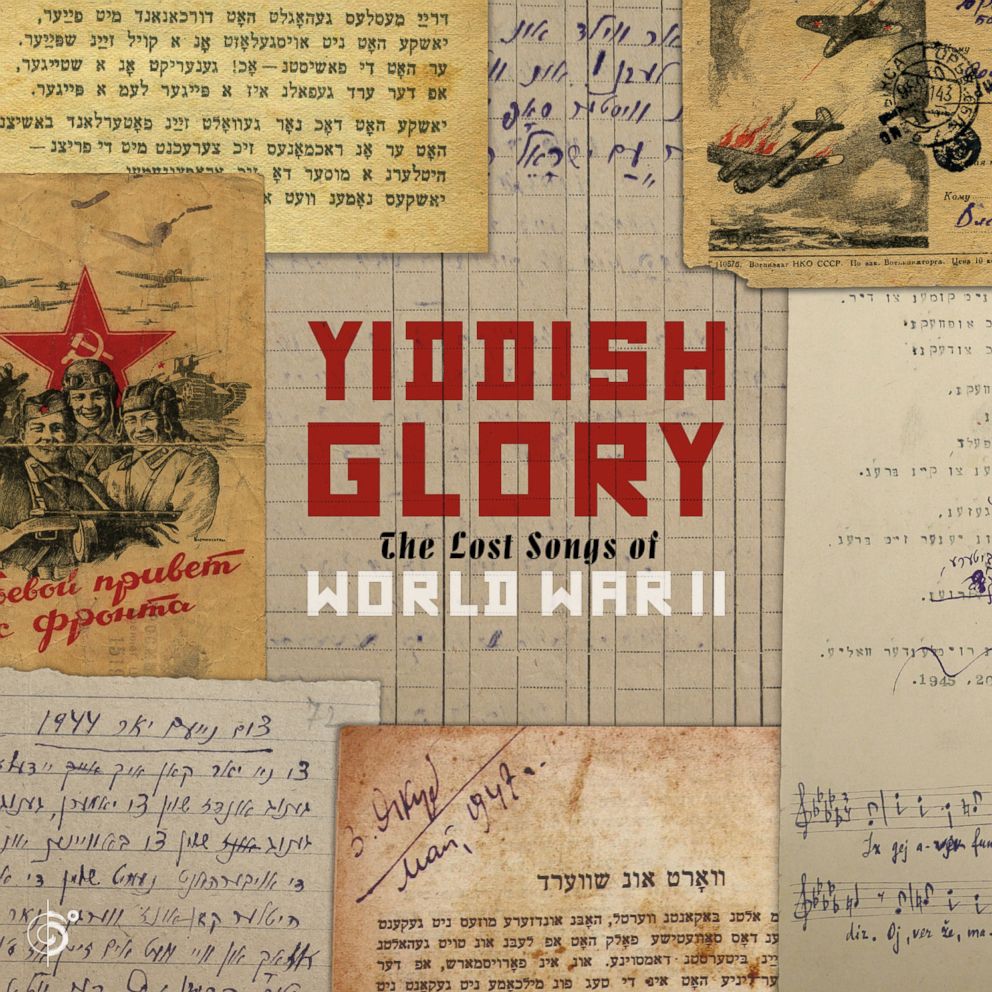

In 2010, Shternshis started studying a collection of Yiddish songs lying in unmarked boxes stored in the basement. The songs were written mostly by women and children in the Soviet Union during the Second World War and talked about the experience of Holocaust and the role of Jews in fighting the Germans in the Red Army.

These songs were originally collected by Moisei Beregovsky, the preeminent scholar of Jewish music in the Soviet Union who was arrested by Stalin. Most of his work was published after he died in 1962 since Jewish studies were illegal in the Soviet Union at that time.

Reviving Soviet-era Yiddish songs

To revive the songs and add tunes, Shternshis collaborated with singer-songwriter Psoy Korolenko and roped in classical and jazz musicians to create an album, “Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of World War II” that was released by Six Degrees Records this February.

The revived songs shed light on everyday life and death of Jews in the Soviet Union during the war and Holocaust in the voices of the people who experienced it first-hand. Nearly 70 years after they were first collected – and thought to have been lost – Shternshis believes their cry against fascism is relevant today as well.

“Only music gives them emotional power … so devastating around them, putting it in words in prose would not be enough,” Shternshis told ABC News.

The songs glorified Stalin and were part of a larger Soviet culture in which music was believed to inspire soldiers on the frontlines -- a tradition that goes back to the Russian revolution.

Many of the tunes were borrowed from popular Russian songs of the time like Mikhail Glinka’s “Lark,” a song Korolenko heard as a lullaby.

“We imagined someone loving this song and, if he wanted to create a song, then why wouldn’t he be singing this to the tune of Glinka? This is how it works,” said Korolenko.

"A closed-off history"

The dominance of the western narrative of the war and Holocaust coupled with post-war state-sponsored-anti Semitism in the Soviet Union resulted in the under-documentation of Soviet Jewry, the largest community in Europe after the war.

“It’s part of a much bigger history that was shut down, that history was closed off,” said Bret Werb, a musicologist at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Werb believes that one of the biggest contributions of the revival effort is garnering attention to the efforts of Beregovsky.

“This was a very impressive and difficult post-war collecting effort by Mr. Beregovsky who was back from exile to document the folklore of the Jews who had been ghettoized or put into forced labor during the Nazi occupation in their part of Ukraine,” he said.

The rawness and immediacy of the songs that describe brutal acts of revenge against Nazi Germany infused, at times, with humor during the years of extermination enriches the increasing focus on Jewish Soviet history, according to CUNY professor Elissa Bemporad.

“These songs are part and parcel of what we could call the ‘geniza’ of Soviet Jewry,” she said, referring to the area in synagogues or cemetery that temporarily stores religious Hebrew books. “These are documents in the holocaust, not of.”

Most importantly, she said, the songs rekindle Jewish voices that were silenced twice – first by the Holocaust and later by Stalin’s crackdown.

“We assumed most Jews in the Soviet Union assimilated,” she said. “We superimposed on the Jews of the inter-war period who were exterminated, the Jews of Moscow who was assimilated because those voices were wiped out.”

The songs also describe atrocities in camps that had few survivors.

For instance, “Tulchin,” a song penned by a teenager in 1942, describes the mass murder of Jews in Pechora, a former sanatorium in Tulchin that had 3,000 Jews. Here, the child reminisces the wonderful life he lost before the war and at some point says, “People here are dying like flies. And there are always lonely orphans wandering about the road and nobody will ever remember us.” The writer fled in 1943 and sang for Beregovsky in 1944.

“We didn’t have almost any materials from the place,” said Shternshis. “Pechora is obscure … But these songs give a chance to hear what it’s like in Pechora.”

Drawing attention to vulnerability caused by war

Over the last few months, Shternshis and Korolenko have performed these songs at universities across Canada, Germany, Belgium and the U.S and in the coming weeks are touring New York’s Center for Jewish History, Northwestern University and Purdue University. A large-scale concert in Toronto, and perhaps New York in 2019, is being discussed.

Apart from celebrating Beregovsky, Shternshis hopes these songs draw attention to the vulnerability of children in wars today.

“I want people to think about the war, the political acts of violence,” she said.

Milman said she was driven by the idea of contributing to the relatively unknown duality of the Soviet Jewish narrative – victims of the Holocaust as well as heroes in the Red Army who liberated Auschwitz.

She said her grandparents, who now live in Moscow, avoid talking about the war, but were excited about the album.

“It definitely stirred something,” she said. “But again, they don’t want to think about it.”

Shternshis and Korolenko will be performing "Singing and Laughing at Fascism" at Center of Jewish History, New York on April 9, 2018.