Shimon Peres: The Legacy of Israel's Last Surviving Founding Father

Israel's longest serving statesman Shimon Peres died early Wednesday.

JERUSALEM -- Israel's longest serving statesman Shimon Peres died early Wednesday, leaving the country mourning the last of the state’s founding fathers and a man whose legacy as a would-be peacemaker is celebrated by supporters but eyed with skepticism by many Palestinians.

The Sheba Medical Center in Tel Aviv said Peres, 93, died two weeks after suffering a serious stroke that caused bleeding in his brain.

Peres was present at the birth of the State of Israel. He emigrated from Poland to Palestine, then under British rule, in 1934 with his family when he was 12 years old. He grew up with the young nation, attending a school advocating for the relocation of Jews and as a teenager joined the first generation of Zionists in politics, led by David Ben-Gurion.

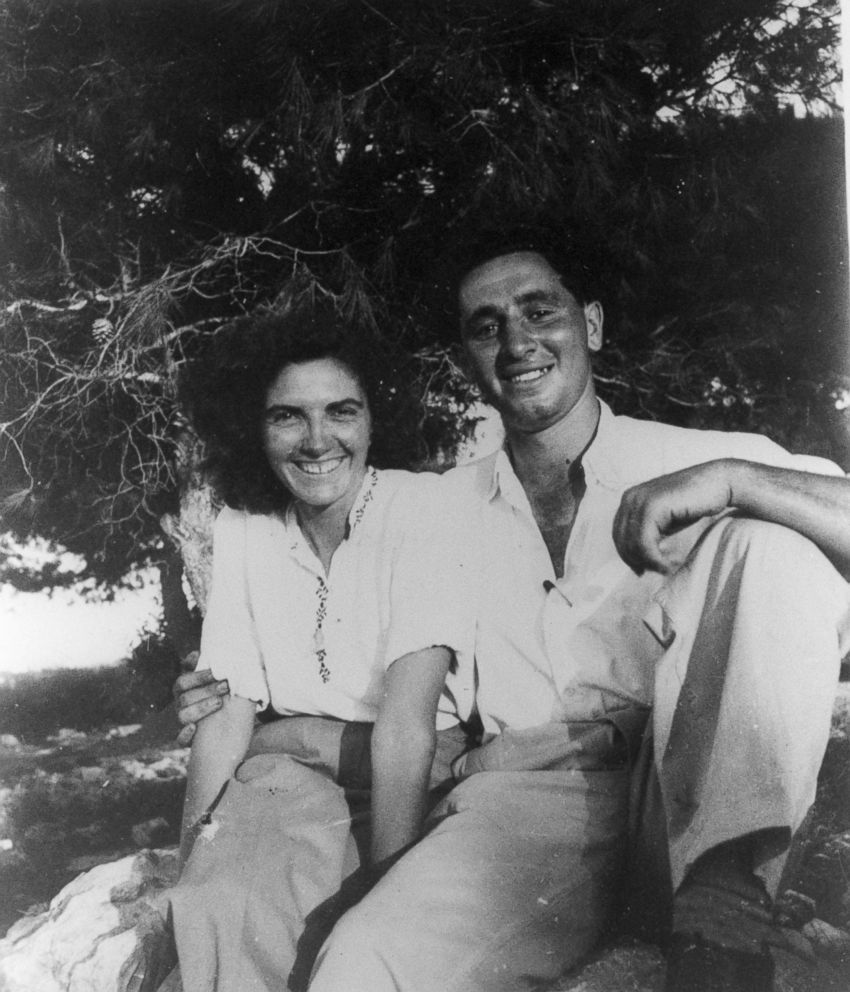

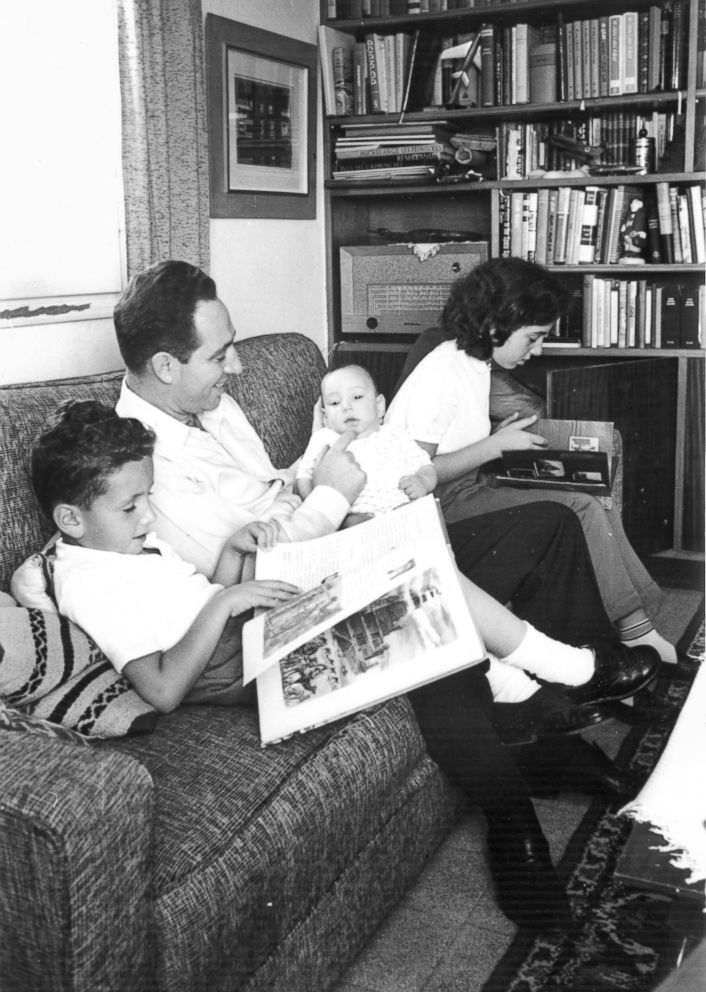

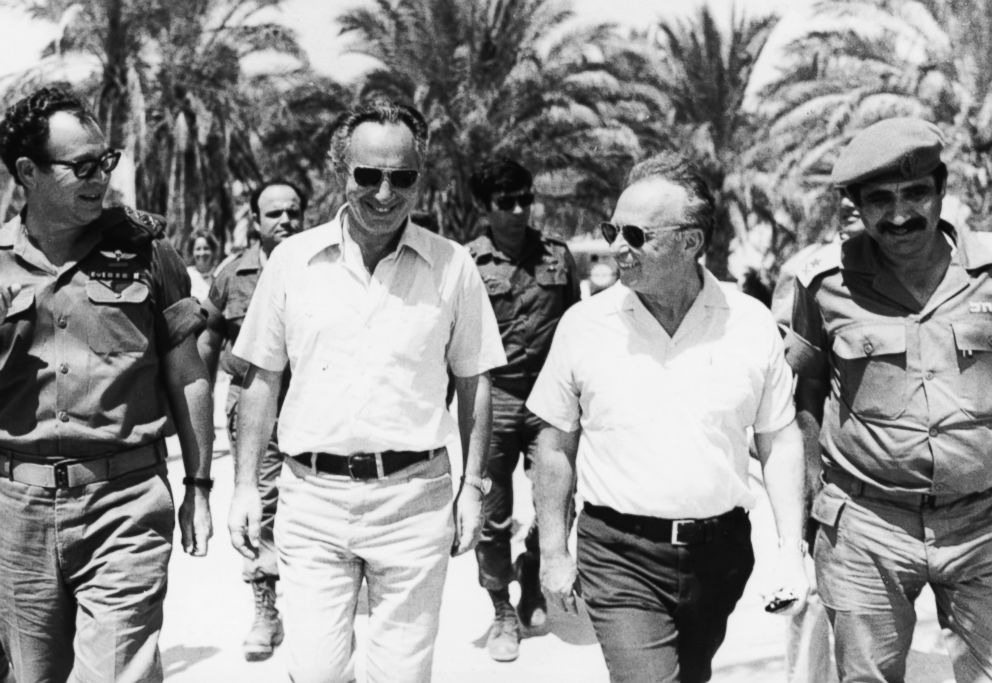

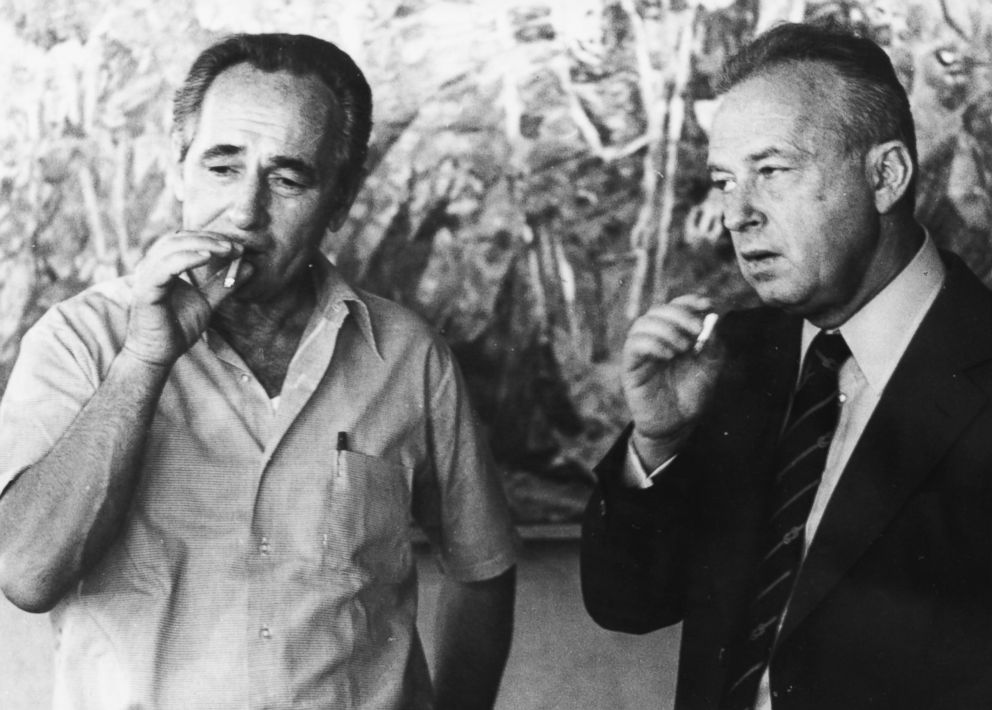

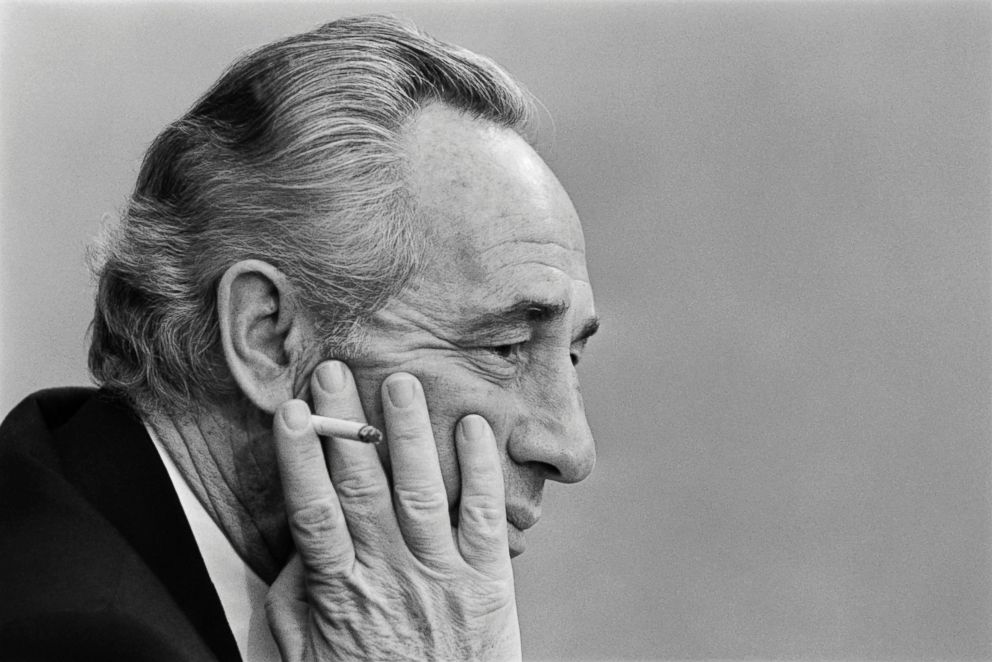

Shimon Peres Through the Years

"Shimon was the essence of Israel itself," President Obama said in a statement Wednesday. "The courage of Israel’s fight for independence ... and the perseverance that led him to serve his nation in virtually every position in government across the entire life of the State of Israel."

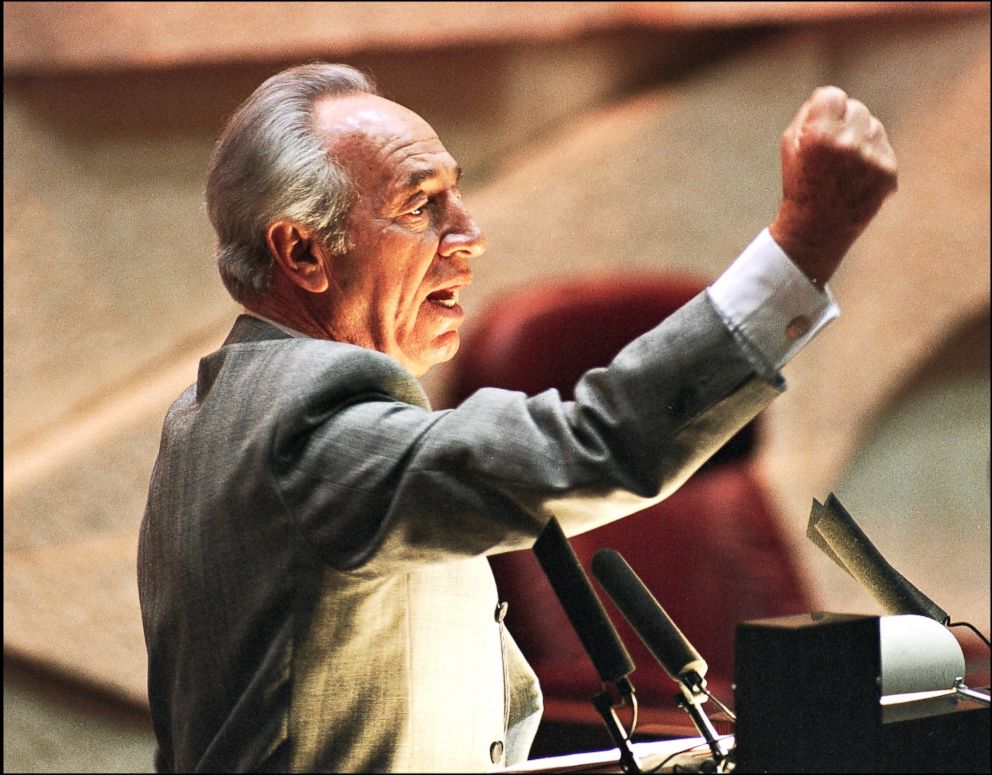

Peres' career spanned 10 U.S. presidencies. He served in the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, for over 47 years, and was elected prime minister three times. Peres was present at nearly every key moment in Israel's history.

"As a man of vision, his gaze was aimed to the future," Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Wednesday. "As a man of security, he fortified Israel's strength in many ways, some of which even today are still unknown."

His reputation was never without controversy, but his popularity grew enormously in the last 15 years of his life.

"He became the darling of the nation," said Peres biographer Michael Bar Zohar. "He wanted to be loved by the public."

And he was, at times.

"Sometimes the world is divided between the dreamers and the doers," said Yehuda Ben-Meir, a former deputy minister of foreign affairs and a member of Knesset. "He was a dreamer, he was a visionary, but Shimon was also a builder. He managed to combine the two."

Peres built Israel's defense industry from scratch in the 1950s, negotiated Israel's biggest arms and technology deals and prioritized security above all else. He dealt secretly with European powers, and was the mastermind behind Israel's nuclear power plant Dimona, which houses a 24,000-kilowatt reactor in the Negev desert.

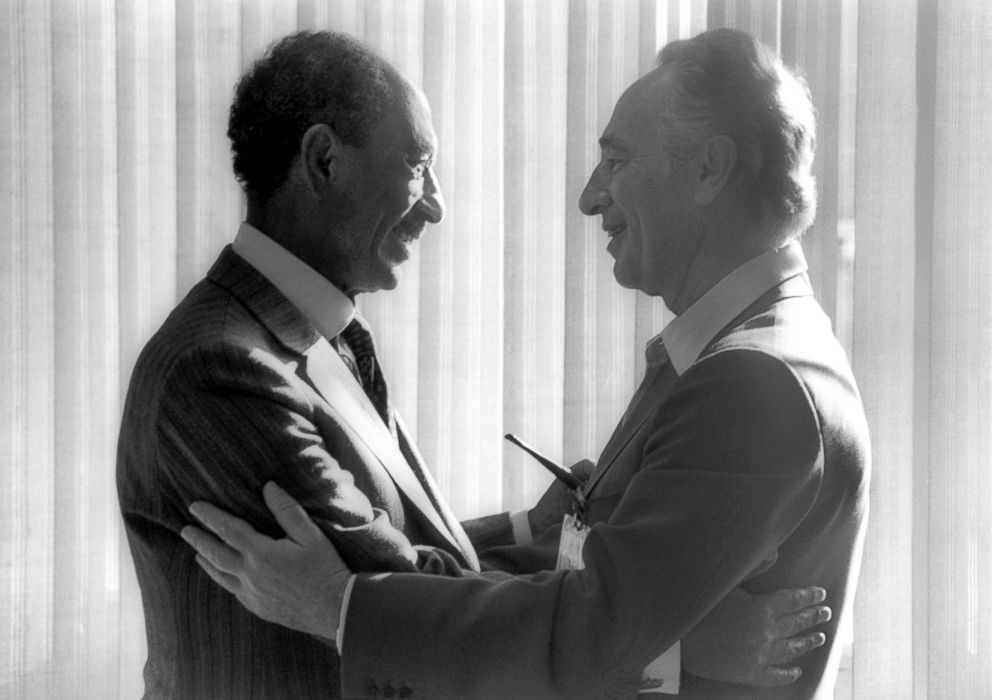

Two decades before the Oslo Accords and his subsequent Nobel Peace Prize, shared with then-Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yassar Arafat, Peres was a staunch supporter of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank.

As defense minister, he encouraged Jewish settlers to move to the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and to the Golan Heights. Some 10 years later, he set his sights on peace with the Palestinians, and to this day, that very peace remains elusive in large part due to the expanding Jewish settlements, according to the United Nations.

And Palestinians remember that.

For Israelis, even those that opposed the Oslo Accords, the Nobel Peace Prize cemented Peres' legacy as a "man of peace," but for Palestinians, despite the flicker of hope before Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's assassination in 1995, the impact of settlement expansion and a powerhouse Israeli military leave a cruel legacy, said Diana Buttu, a lawyer who was involved in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations.

"He was the first to do a number of things," said Buttu. "Setting up Dimona nuclear facility without inspections -- that created a precedent that stands today. And the bombing of Qana, Lebanon, in 1996 where 800 people were seeking shelter in a UN building ... it then became acceptable to bomb UN facilities."

She continued, "For Peres, 'peace' meant bombing civilians, stealing land, ethnic cleansing and building settlements. He stripped the word 'peace' of any meaning."

For his part, Mahmoud Abbas, president of the Palestinian National Authority, sent a message to the Peres family expressing his sadness and regret in losing "a partner in brave peacemaking." The message praised Peres for making "relentless efforts to achieve lasting peace since the Oslo agreement until the last moment of his life."

The struggle between security and peace dominated Peres' later political life but he never showed regret.

"Shimon was an optimist," said his biographer, Zohar. "He never looked back in anger. If he did regret, he did not show it."

Years later, when asked about his change in priorities, he told Newsweek: “It’s not that I changed my character. I found a different situation."

He worked tirelessly and his peers say nothing was ever enough.

"He was a fighter. He never gave up," said Ben-Meir. "He knew how to give them hell. And knew how to build."

Zohar describes it this way: "When [Peres] was 4 or 5 years old in Poland, he would go to his grandmother's house with a friend who was much stronger than him. They played a game that involved the stronger friend pushing little Peres down again, and again. Finally Peres' grandmother put an end to it and Peres protested. 'But perhaps next time I'll make it!' he said, and that was Shimon Peres from age 5 until his death."

An eternal optimist, he told Zohar once, "I never met a pessimist who found another star in the sky."

And when asked about his legacy, Zohar said, "I don't think he cared about it very much."

"People ask me how I would like to be remembered," Peres told the Sunday Times in a 2013 interview. "I say bubbemeises [nonsense] — no one remembers anything."