What it's like in the Venice flood: Reporter's notebook

Locals are still waiting on a 2003 dam project to help with the floods.

Venice was built to survive flooding. Standing on St Mark’s square just before midnight, and the next high tide, we watched as drains that crisscross the piazza started to bubble over. Within 30 minutes, about a foot of water had risen, like some sort of baptismal font right in front of the world-famous St Mark’s Basilica.

When the earliest settlers came to the islands that make up modern Venice, they too may have experienced flooding. And as the city grew over the centuries, its architects and conquerors built structures that could survive a volatile sea. That’s why there are drains all over the city. It happens that St Mark’s Square is at the lowest point, right on the Grand Canal that opens onto the lagoon, which means it suffers the most dramatic inundation.

But the city is now being tested to its limit.

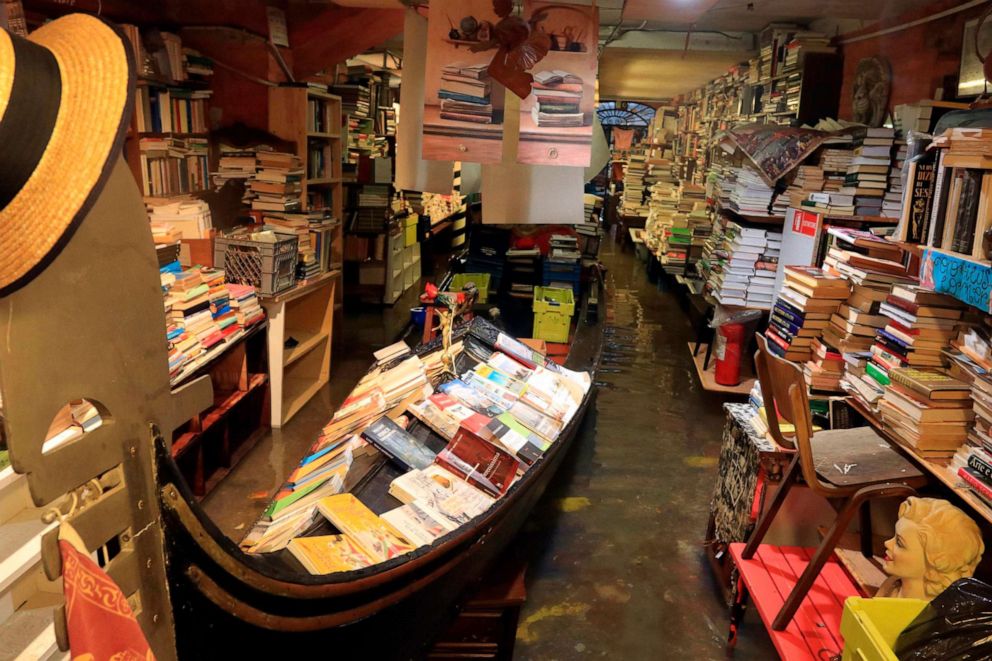

Wading through it is quite surreal. With the water lapping almost to our hips, we went past building after building - many homes and businesses - under several feet of water. Gondolas were bobbing on the surface, lifted by the rising tide, making it difficult to distinguish between canal and sidewalk.

It’s become something of an attraction for the tourists, who, with their shoes and trousers covered in plastic, venture out into the flood to take selfies. The locals look on, standing in the doorways of their sodden shops or cafes. Their misery seems to provide others with some unique entertainment.

It’s difficult not to feel sorry for them, and angry on their behalf. A lot has been made of climate change and rising sea levels, and there is no denying the floods are getting worse. Standing in the damaged crypt of the basilica where he’s in charge, 81-year-old ‘procuratore’ Carlo Alberto Tesserin remembers his childhood fondly. ‘When I was a boy, the flooding was normal. We wore boots and ran around in the water.’ But now he says, things are different. ‘Even these long waders are not enough. The water is deeper.’

But climate change might also be a convenient excuse to frame the flood problem as an inevitability, when, in fact, people here are angry with their politicians for the delays to Venice’s one hope: The Mose Project.

Building started in 2003 for a vast underwater dam that would cross the entrance to the lagoon. At high tide, the idea is for it to rise out of the water and keep the worst of the ocean water out. But despite billions of Euros, it’s still not finished and has been marred by allegations of corruption. It’s not clear whether even when finished, this barrier would work. Environmentalists are also concerned about the impact a stagnant lagoon would have on wildlife. But it’s the only plan at the moment.

Given other low lying parts of the world have mitigated their issues, it’s troubling that one of humankind’s most important cultural and architectural treasures has been left to suffer in this way. In the Netherlands, successive governments have overseen massive engineering projects displacing millions of tonnes of earth into the ocean to keep their country above water. I think of my own city, London, where the extraordinary Thames barrier keeps the power of the river at bay.

Much of Venice is built on stilts sitting in mud - meaning some areas have slowly sunk over time.

But whatever the causes, the solution seems within reach.

Venice is a marvel of human design and ingenuity; if the Mose Project were to be completed, it would be a spectacular, modern contribution to that legacy. Without it, so much will be lost.