Photographer captured faces of the American South during Jim Crow

A new book reveals the work of 19th century photographer Hugh Mangum.

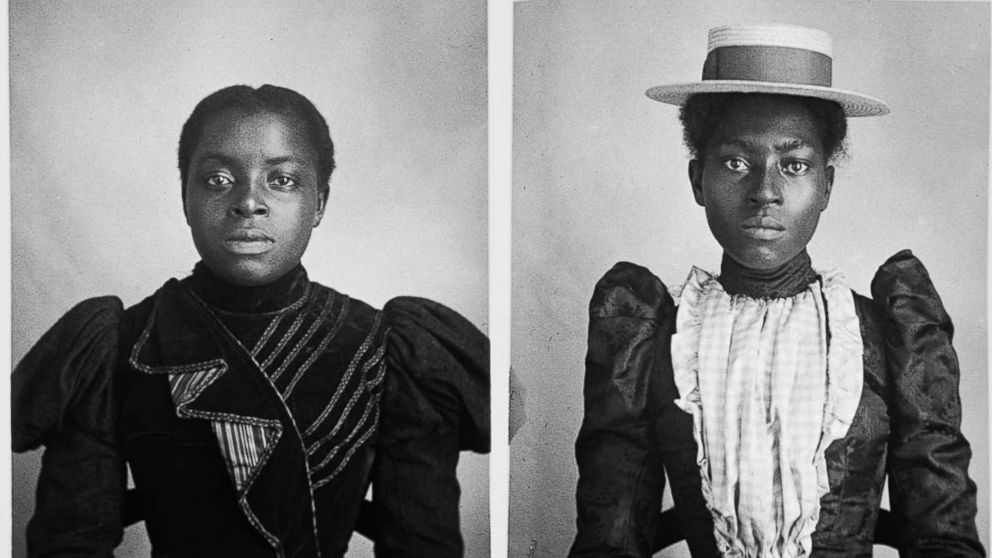

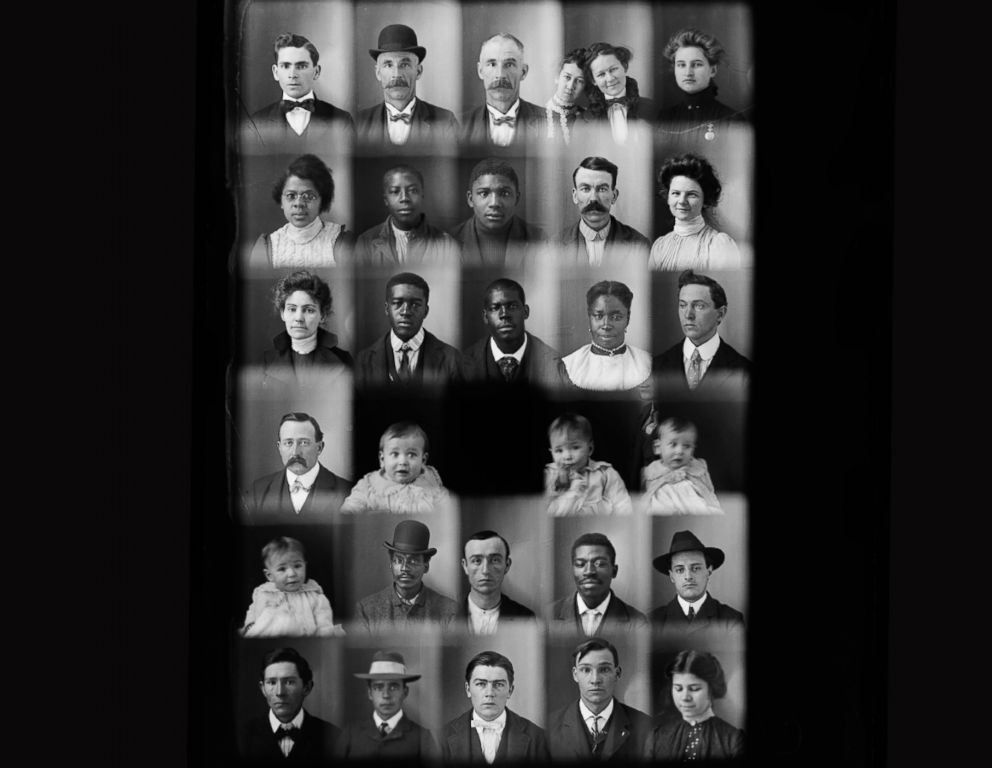

Solemn-looking men, well-dressed women and confused-looking babies all sat still for Hugh Mangum to take their picture.

A new book, “Photos Day or Night: The Archive of Hugh Mangum,” is the first published collection of the work of this 19th century photographer, and it offers a rare glimpse into everyday life in the American South following the Civil War and Reconstruction.

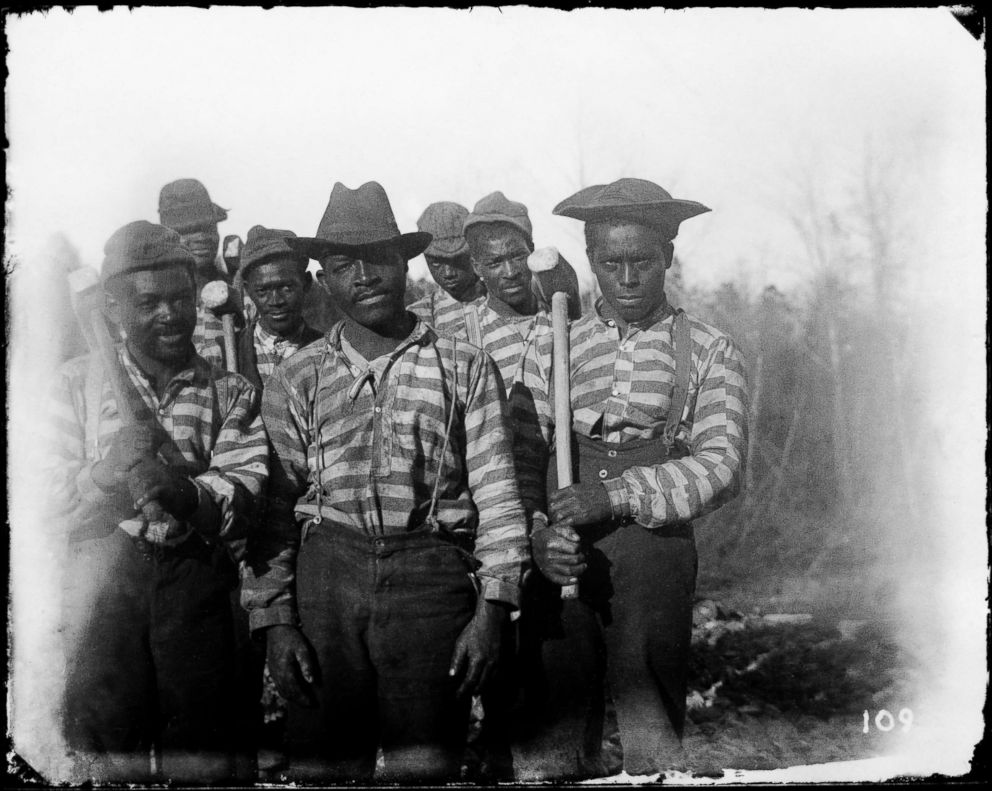

After the Civil War, federal laws were put in place to provide civil rights protections for African-Americans. In 1877 the federal government withdrew its last troops from the region, after which Southern politicians resumed power and created Jim Crow laws, legally segregating the black and white populations.

Mangum worked in his native North Carolina, as well as Virginia and West Virginia, and traveled throughout the region setting up his photography studio in tents or shops. He made his living selling penny portraits to whoever wanted their photograph taken.

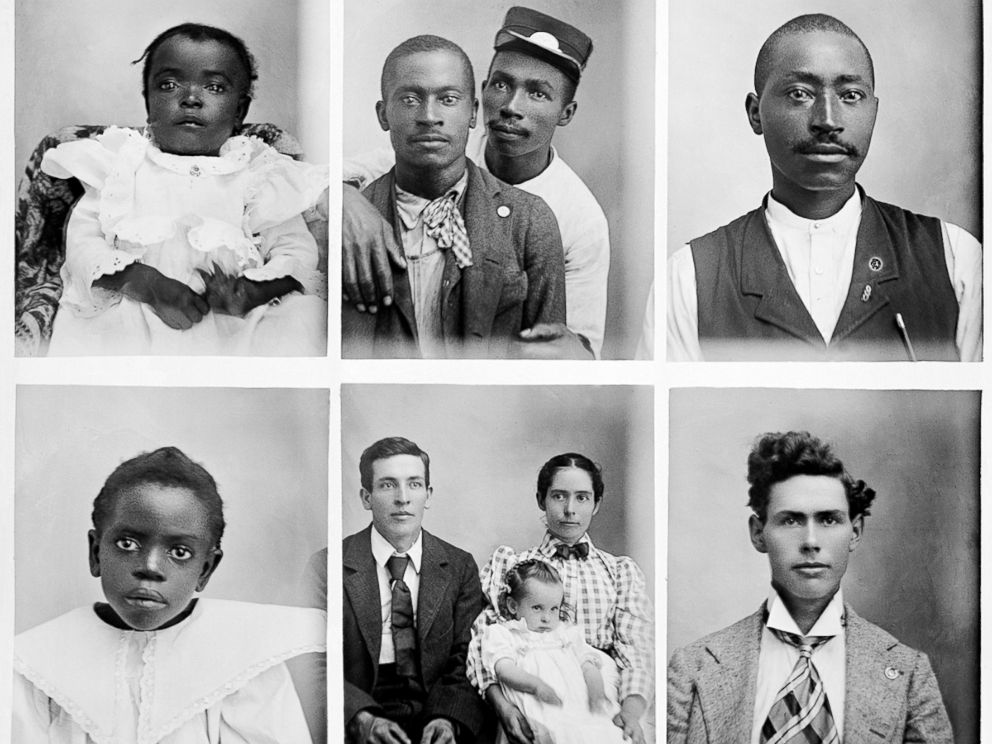

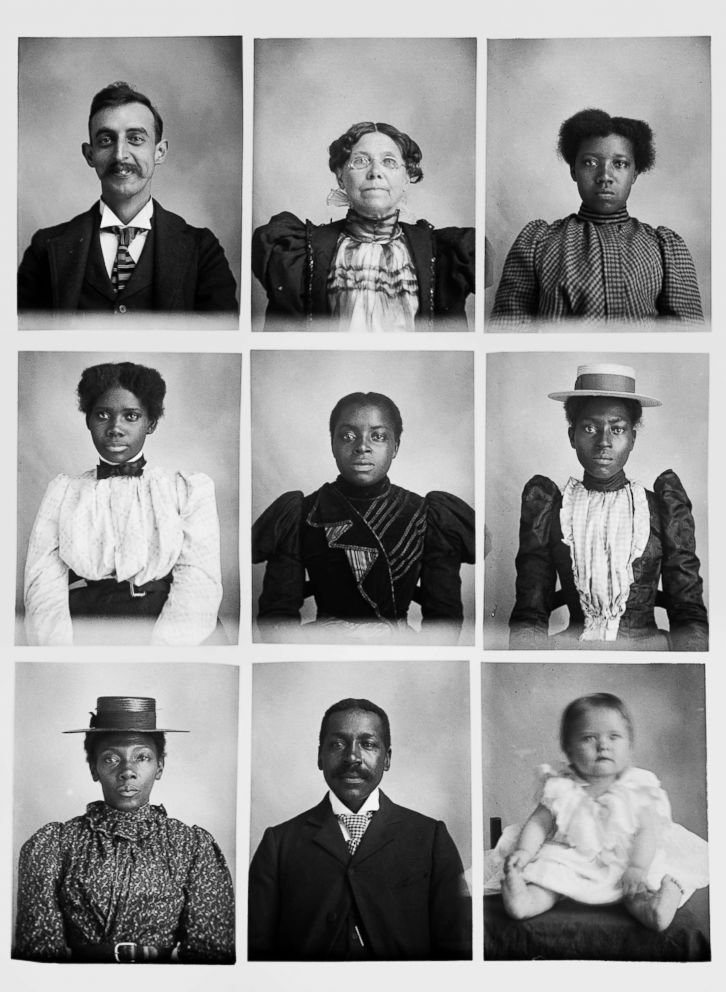

The camera Mangum used was designed to create multiple and distinct exposures on a single glass plate negative. Lined up in neat rows on a single glass negative, the sequence of the images shows the order in which Mangum’s diverse clientele came through his studio. Often, a single negative reflected a day’s work for Mangum.

Sarah Stacke, a photographer and the author of “Photos Day or Night: The Archive of Hugh Mangum,” discovered his work while in graduate school at Duke University, where Mangum's archives are kept.

"Mangum's studio was a rotating door of diversity,” Stacke told ABC News. “From what we can see from his pictures, he treated all clients the same and approached everyone as unique with a different story to tell."

"On several occasions the elbow, hand, or arm of one sitter floats into her neighbor’s frame, regardless of color, symbolizing shared spaces beyond the boundary of the negative,” Stacke writes in the book. “There are double exposures that photographically merge black and white sitters, and through this lawless, accidental composition that binds them forever, we begin to imagine both the common and distinct experiences of those pictured. One supposes that Mangum’s clients briefly or lingeringly occupied the same room, unified in a quest to arrest their likeness in a photograph."

Professor Maurice Wallace of the University of Virginia (UVA), contributed to the book and brings a unique perspective to the narrative. Wallace did his dissertation on the history and politics of black masculinity in African-American literature and culture. He describes Mangum’s work as subverting the cultural and political norms of the day.

"Hugh Mangum’s photographs forcefully betray that vision of the South’s strict and thorough segregation usually identified with Jim Crow,” Wallace told ABC News. “The color line was of course an official policy, but practically speaking its power to keep black and white citizens apart was a fantastic fiction."

"These are often counter-images to the caricatured images of black and brown and working folks that served the pretentions of the elite in mass culture,” Wallace tells ABC News. “Though often light in bearing, there’s nothing in Mangum’s pictures of African-Americans, for example, that relies on the racist iconography of blackface minstrelsy. It would have been easy for Mangum to do that. He didn’t. It seems he mocked himself more than anyone."

"A century after their making, Mangum’s photographs allow us a penetrating gaze into faces of the past, and in a larger sense, they offer an unusually insightful glimpse of the South at the turn of the twentieth century," Stacke writes.

by Sarah Stacke, with texts by Maurice Wallace and Martha Sumler, Hugh Mangum’s granddaughter