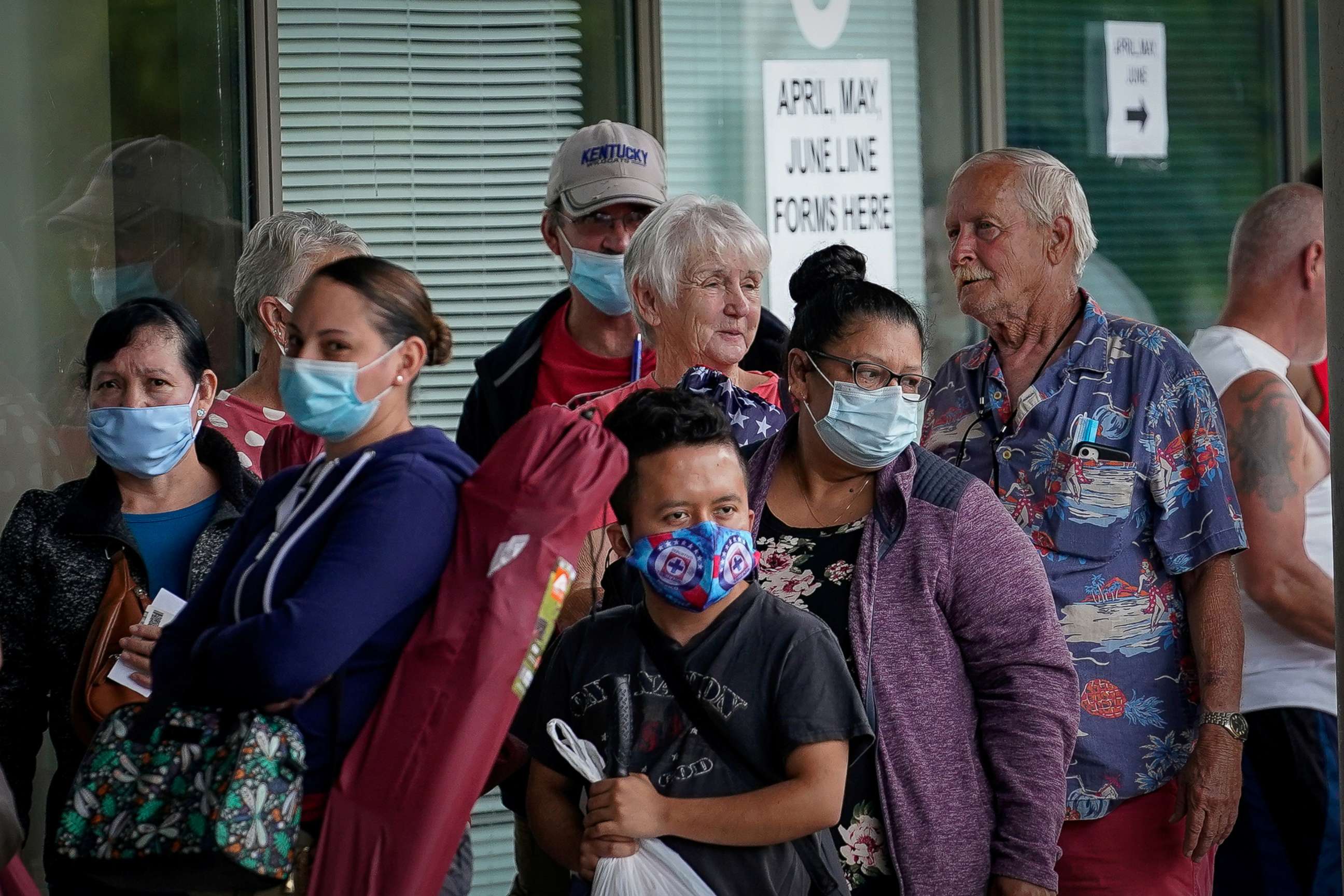

30 million Americans set to lose $600 weekly benefit amid COVID-19 pandemic

Congress and the White House are far apart on a meaningful deal.

As federal pandemic unemployment benefits officially expire on Friday, Congress and the Trump administration are no closer to a deal that would salvage any portion of a $600-per-week check that, as of last weekend, would affect some 30 million Americans.

A last-ditch effort was mounted by Senate Republicans Thursday evening, with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell pulling back members -- many had already left for home for the weekend -- to vote on a plan that would cut the weekly federal benefit to $200, or two-thirds of lost wages. Democrats unanimously opposed the measure, authored by GOP Sens. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin and Indiana's Mike Braun, saying the effort was merely a cynical political stunt after the majority dithered for months.

Democrats also refused to accept a seven-day extension of jobless benefits, saying any such extension would be pointless given that no deal is in the offing.

"What is a one-week extension good for? A one-week extension is good if you have a bill and you're working it out -- the details, the writing of it, legislative counsel ... that's what a one-week extension is about. That is, it's worthless. It's worthless unless you are using it for this purpose," House Speaker Nancy Pelosi told reporters after a late-night meeting between herself, Senate counterpart Chuck Schumer of New York, White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

House Democrats passed a bill more than two months ago that would keep the jobless benefits at the current rate through the end of the year, part of a $3 trillion bill that would provide funding to front-line workers, the health care industry, schools and state and local governments.

Republicans have argued that businesses haven't been able to rehire workers who now may be taking in more from unemployment benefits than they would from returning to jobs.

Senate Republicans introduced a $1 trillion package this week that contains a liability shield to protect businesses, schools and other institutions from coronavirus-related lawsuits; gives $105 billion to schools, with two-thirds going to those that reopen; distributes another round of $1,200 stimulus checks to lower-income Americans; provides money for COVID-19 testing and to health care agencies at the center of the pandemic fight; and provides tax credits to hard-hit businesses.

But a number of Republicans rejected that proposal, leaving GOP leadership in the difficult position of needing a sizable number of Democrats to pass that. Republicans also have had to contend with bipartisan blowback from a number of extraneous, White House-requested spending measures unrelated to the pandemic -- $1.8 billion for a new FBI headquarters and $377 million for long-sought West Wing renovations.

The stalemate on a single issue -- jobless benefits -- foreshadowed a steep climb to any overall coronavirus relief bill as the sides remain far apart on many issues. Republicans and the White House also are not in agreement on how to move forward, creating a difficult environment in which to form a compromise.

Meadows on Friday sought to blame Democrats for the impasse.

"The Democrats have made zero offers -- zero," Meadows said. "We're going in the wrong direction."

But Thursday night, Schumer said it was the White House and Republicans who were out of touch.

"We just don't think they understand the gravity of the problem," the senator told reporters. "The bottom line is, this is the most serious health problem and economic problem we've had in a century and 75 years, and it takes really, good, strong bold action. And they don't quite get that."

Both administration officials and the two top congressional Democrats are expected to resume negotiations Friday by phone with a possible in-person meeting over the weekend.

All of this comes as House Democrats allow members to leave on a month-long recess, with their leadership warning them to be ready to return should a potential compromise emerge.

It's a sign of what many on both sides already know: That no deal is likely to emerge for weeks, if at all.