Michigan Lawmakers Caught in Extramarital Affair Cover-Up and Aides Who Exposed Them Speak Out

Todd Courser and Cindy Gamrat were both married with kids during their affair.

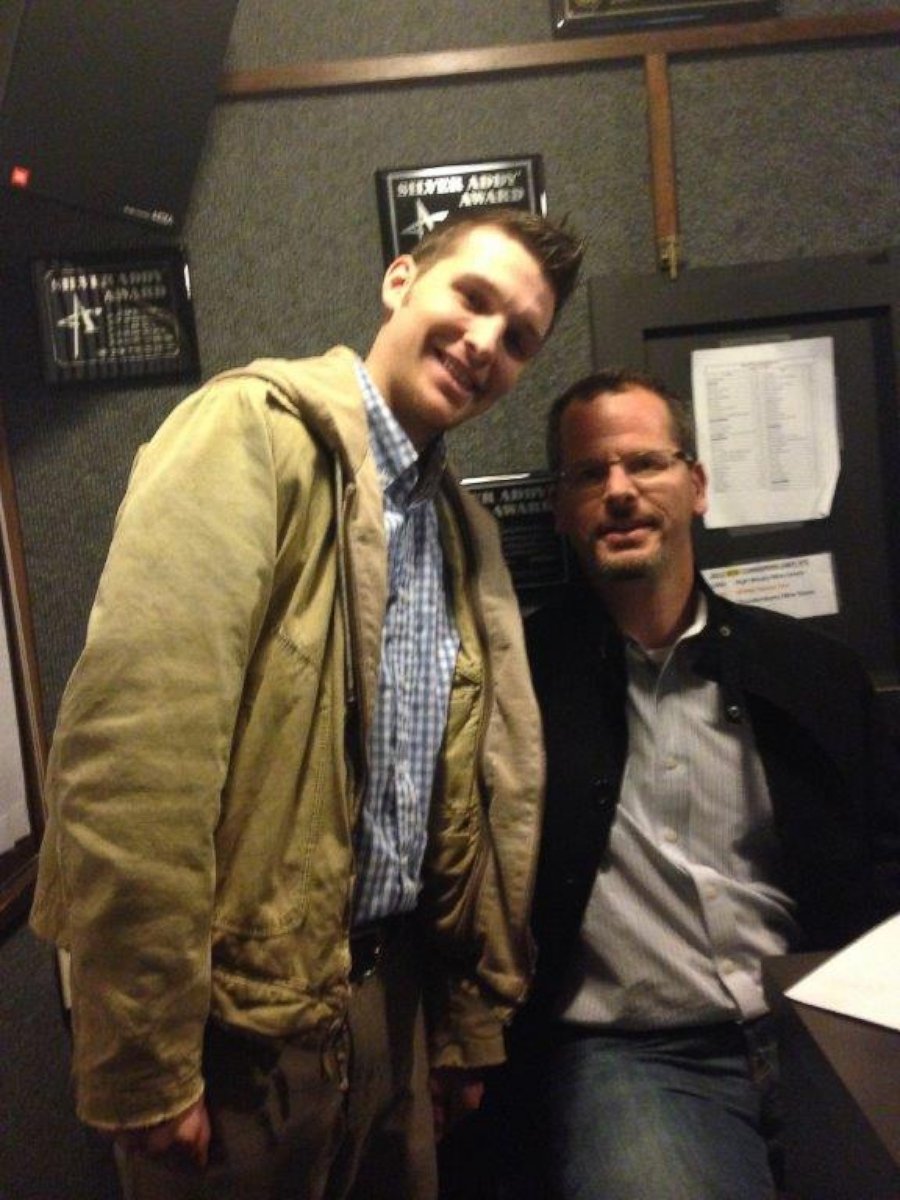

— -- It was late at night on May 19, 2015, when Ben Graham got a strange phone call from his boss, then-Michigan State Representative Todd Courser, asking him to come to his law office in Lapeer, Michigan, as soon as possible.

"In a very, the most serious tone I've ever heard from him, he said, 'Ben, I need you to destroy me,'" Graham told ABC News' "20/20." "And I paused for a second and I said, 'Todd, what do you mean?'"

"He's like, 'I need you to destroy me. Can you come to my office?'" Graham continued. "I asked him what was going on, he said, 'I can't tell you, come to my office.'"

Before heading out, Graham said he immediately notified fellow aide Keith Allard and another aide that Courser was asking him to meet late.

"This is a guy who has been showing increasingly unstable signs ... in terms of his anger issues and communications towards us," Allard told "20/20." "There's a 20 percent chance he might act out violently towards himself or others and he kept a loaded gun in that office, so I advised Ben, 'record the conversation.'"

"You don't want to be left in a room with a smoking gun trying to defend yourself against something that happened in there," he added.

The conversation Graham would record that night in Courser's office would expose the extramarital affair Courser was having with another Michigan state representative, Cindy Gamrat, and ultimately lead to their ouster from the Statehouse.

"I couldn't believe what he was asking me," Graham said. "And I couldn't do it."

Now, Gamrat, Courser and their aides are sitting down with ABC News' "20/20" to share with what they say really happened that led to all of them losing their government jobs.

Cindy Gamrat and Todd Courser were Tea Party darlings from conservative districts when they were elected to the Michigan State House of Representatives in November 2014. When the two Republican freshman reps took office on Jan. 2, 2015, they allied themselves. They combined staffs and worked out of the same office, and were said to go after just about everyone in the House, even those in their own party and the state's Republican governor.

"They did not form relationships with their colleagues except for each other," said Keith Allard, a former Gamrat staffer. "Todd actually kind of declared public warfare on his colleagues, I mean, just putting out missives, trashing them left and right."

By spring 2015, the duo had alienated most of their House colleagues.

At the time Courser and Gamrat took office, Courser had been married to his wife Fon, an immigrant from Thailand, for 18 years and Gamrat married her high school sweetheart, Joe Gamrat. Courser has four children and Gamrat has three.

While in office, the two lawmakers grew close. After late-night sessions at the State House in Lansing, the two would at times spend the night at the Radisson Hotel downtown instead of making the long drive home. The aides said Courser and Gamrat routinely shrugged off questions about how much time they spent together.

"One member of our staff said to them ... 'you need to consider the optics of the situation and how much time you're spending together, the late nights in Lansing'" Allard said. "They laughed it off. They just -- it was a joke to them."

However, it turns out that Courser and Gamrat actually were involved in a love affair, despite their Christian and traditional family values beliefs.

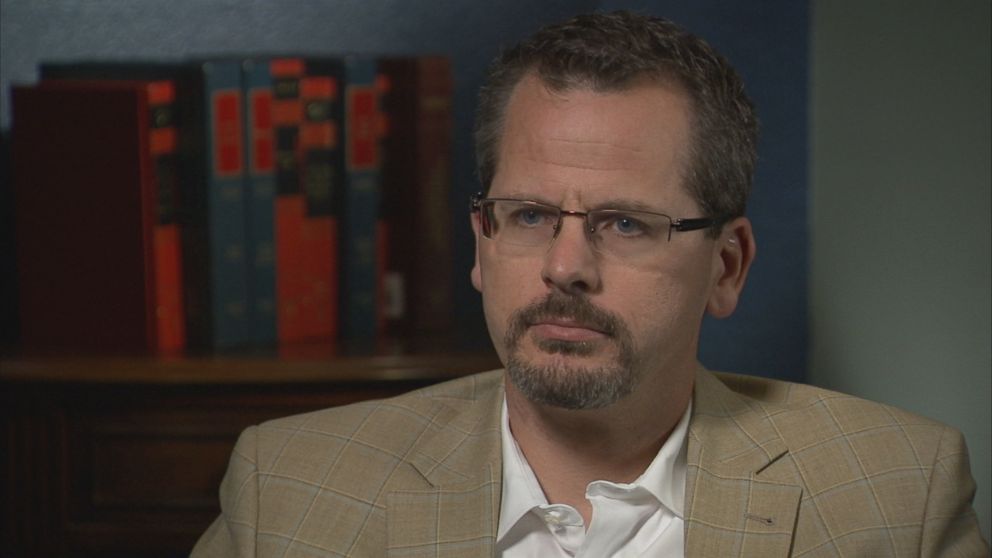

Courser acknowledged to "20/20" that he could be viewed as a hypocrite. "Everybody would hear that I'm a believer in Christ," Courser said. "They wouldn't hear the part that I'm failed and flawed, you know, like everybody else."

The affair continued into May, when Courser said he began receiving a series of anonymous text messages threatening to expose Courser's affair with Gamrat, saying things like, "Cindy sounds like she's great in the sheets," and "Silence in this case can be VERY detrimental ... it could be disastrous, really." Courser said the texter made references to details from Courser's private phone calls and his trips. The texter had even told him his "phone was a burner" so "don't bother trying" to track it.

"They knew my emails out of my outbox, even after I changed my password," Courser said. "They knew texts from my phone."

Then the texter had told Courser he would keep quiet about their affair and "everybody off the hook ... on 1 condition. You resign Todd."

Courser said the text messages drove him over the edge and that he was on the verge of a major breakdown.

"You're becoming personally just worn down one moment after another," he said. "Mentally, spiritually and physically, you can't do it."

Courser's aides said his behavior began to darken and he started venting his frustrations on his staff.

"Todd is usually very chipper and sarcastic and fun," Graham said. "But there would be times where he would take things out on us with a great deal of anger that I felt was inappropriate ... and I wasn't just a staff member, we were friends. ... It was tough."

Then things took a strange turn that night on May 19, when at 10:30 p.m., an anxious Graham walked into Courser's law office.

Graham secretly started recording their conversation on his cell phone. On the recording, Courser is heard explaining to Graham that he wants him to send an anonymous email to fellow House Republicans to purposefully spread shocking lies about himself -- that he paid for sex with a male prostitute, which Courser said never happened.

"It's already written, I didn't print it. I don't know what God'll do, buddy," Courser recalled, then reading the email he wrote aloud, "'Todd Courser caught on tape behind Lansing nightclub. In truth, Courser secretly removed from caucus several weeks ago due to a male-on-male paid-for sex. He is a bisexual, porn-addicted sexual deviant.'"

"And then you just get nasty about it," Courser continues, and then reading, "'His **** is hanging out all over Lansing since the election ... gun-toting, Bible-thumping ... freak ... he doesn't work in Lansing. He's just there feeding his habit of alcohol, drugs and illicit sex."

Graham said he was stunned not only that Courser would ask him, but that he would say such things in the first place, especially to lie about himself.

"I need it to be over the top," Courser is heard telling Graham on the recording.

"Nobody's going to believe it," Graham said to him.

"You're correct ... I'm not a homosexual ... I don't do alcohol, I don't do drugs, right," Courser responded.

"That's what I mean, that's why it's not believable" Graham told him.

"Right, but they don't know that," Courser said. "People are so disturbed, they won't print it. But anything after that is going to be suspect. It'll be looking like a complete smear campaign."

"Stuff's going to come out, Benjamin," Courser continued. "And they're going to implicate myself and Cindy Gamrat."

Courser then went on to say that he and Gamrat had agreed on the email. But Gamrat denied having any knowledge of the email plot, and Courser now says she had no idea what he was planning.

"When I heard that audio, what ran through my mind is, 'why did he say that?'" Gamrat said. "I had not seen that email, so I was wondering myself, 'why did he say that' or 'what was he referring to when he said that?'"

Courser claims he devised the bizarre email scheme out of desperation to smoke out the mystery texter.

But on Graham's recording, Courser revealed another motive. He seemed to believe the self-incriminating email would somehow protect him from the real scandal that the texter was threatening to expose.

"The way to handle it is to do a controlled burn of me. It's so over the top that people will see it and they'll be like, 'holy ****, what is that?'" Courser is heard telling Graham on the recording. "And anything that comes after that will be wild by comparison."

Graham said he left the meeting shaken, and said he "texted him back and said, 'Todd, I can't help you do this. I can't help you cover it up.'"

So Courser decided to personally blast out the email to a Republican mailing list under a pseudonym. Eventually, it landed in Detroit News reporter Chad Livengood's inbox.

"It got forwarded all around to a lot of people," Livengood told "20/20." "Initially, it was bizarre. It was like, 'what in the world could this be about?'"

Then, in July, Livengood got a phone call from a source who "indicated that Ben Graham and Keith Allard would like to meet," he said. At the time, Graham and Allard had been fired and wanted to talk. The two were fired for poor performance, but both allege that the real reason was because they knew too much about the affair and email scheme. They have sued Courser and Gamrat and the Michigan House for wrongful termination.

"I felt that it was important for people to know the truth about these people, and what they were doing," Graham.

On Aug. 7, 2015, Livengood published a front page story detailing the recording, proving Courser had made up the email to mask his extramarital affair with Gamrat, and that Courser had originally asked Graham to send it for him as a cover before he sent it himself.

Listening to the recording now, Courser said it's his voice, but he doesn't recognize the person making those demands.

"Obviously there's a lot going on inside of that and the amount of pressure -- it was really intense," he told "20/20." "Inside of that, at that moment ... in the darkness of where I was at, this personally ... I wanted to die, you know. ... I honestly wanted to be done."

The scandal spread like wildfire and rocked the representatives' Christian-conservative districts. Both Gamrat and Courser made public apologies, but the House launched an investigation.

A report released on Sept. 1, 2015, stated the two reps had committed "numerous instances of deceptive, deceitful and outright dishonest conduct" and that they "abused their offices in attempting to cover it up." The report, citing testimony from some of the Reps former aides, concluded that Gamrat was aware of Courser's attempt to convince an aide to send the email for him. While apologizing for the affair, both Courser and Gamrat strongly denied the other allegations in the report.

During a dramatic late-night expulsion vote on the House floor on Sept. 11, 2015, Courser stepped down from office.

"They were not letting us leave until they got an expulsion out of me," Courser said. "They're just ready to get me out of the building, like 'the beast is dead' ... and I just felt like it was done and I walked up and just said, 'hey, you know, I'm going to resign.'"

"You know those lead blankets that they put on you at the dentist? It was like 20 of those came off me as I walked out the door," he continued. "I got in my truck and drove away, and I got about -- I think I got about five miles and I just couldn't move ... and I just pulled into a parking lot ... and I just turned the truck off ... and I didn't move for 12 hours."

Gamrat tried to hold her ground, and the House stayed in session past 3 a.m. that night debating. She too thought about throwing in the towel until she said her 18-year-old son, Joey, told her to stand her ground and told her, "Mom, make them kick you out."

"He knew what I had done and what I didn't do," Gamrat said. "So he said, 'Mom, take a deep breath and hold your head high.'"

In the end, the House voted 91-12 to expel her, making her only the fourth lawmaker and the first woman in state history to be expelled from the chamber. Security escorted her out of the building.

"I didn't expect my term in office to go like this, this isn't how I pictured it," she said. "Regardless of all this pressure ... and trying to learn, and trying to do the best job I could. I did work very hard and it's not how I wanted it to go."

But Courser and Gamrat weren't about to give up that easily. Both ran in the open election this past November for their vacant seats. They pleaded their cases on the campaign trail, telling voters that they want to focus on law and they were still the most conservative candidates on the ballot.

On Nov. 3, 2015, Election Day, Courser lost, winning less than 3 percent of the votes. Gamrat, who garnered 9.3 percent of votes, also lost.

After losing the re-election campaign, Courser re-focused his attention on finding the mysterious texter who harassed him back in May. He was immediately suspicious of his staff.

"If it's connected in any way to state government ... then you have sort of this conspiracy to undo two sitting State Representatives," he said.

Allard and Graham adamantly denied having anything to do with texting Courser.

"For him to say that we were involved in blackmailing him is laughable because if the texter asked him to resign ... I don't have a job anymore," Graham said.

Gamrat's attorney hired a private investigator who was able to find a name on the phone's account. What came up first was the name "C Livingood," which seemed to tie back to Chad Livengood, the reporter from the Detroit News, but the last name was misspelled.

"My initial reaction was that's not surprising that somehow they're going to try to pin this on me," Livengood told "20/20." "But that's not going to work because I had nothing to do with it."

Another local news outlet, MLive.com, hired their own private investigator to look into the burner phone, and this time a different name was uncovered on the account -- "Todd Courser."

"That immediately got our attention," said Emily Lawler, a reporter for MLive.com. "After all, if Courser could concoct a bogus email, why not devise a fake blackmailing text scheme as well."

Determined to clear his name, Courser went to the state police and demanded a criminal investigation into extortion. State police was able to track cell phone GPS data to the town of Port Huron, Michigan, specifically to the Domtar paper plant.

They determined the phone that sent the texts was purchased by a security guard at the plant named David Horr. Investigators then discovered that Horr had been working with an acquaintance at the plant: Cindy Gamrat's husband, Joe Gamrat.

"I was devastated to see the police report," Cindy Gamrat said. "I remember reading the report and just shaking and not wanting to believe what I was reading."

According to the police report, Joe Gamrat, a traveling chemical salesman, had given Horr money to buy the disposable cell phone and then instructed him what to say in the anonymous texts to Courser. The investigation also uncovered a text from Horr to Joe Gamrat that showed he was uneasy about his role in the scheme, writing "I'm kind of freaking out here. I think I should tell the truth."

The prosecutor declined to press charges against Joe Gamrat, saying it wasn't extortion because Gamrat's motives were to end the affair Courser was having with his wife. Horr declined "20/20's" requests for comment. Joe Gamrat denied the allegations in the state police report. He declined to talk to "20/20," saying he wanted to put the whole matter behind him.

The state police report also revealed Joe Gamrat was obsessed with tracking his wife, spying on her for months and planting surveillance devices in her bag and her car. Cindy Gamrat said she found some of them.

"When that is happening to you, it's really traumatizing," she said. "And there's a fear component when you -- a feeling of not feeling safe and secure."

Cindy Gamrat said she plans to divorce her husband. She still lives in the house they raised their kids in when he's away on business, but when he returns home, she said she sleeps in her SUV in a supermarket parking lot. She is now starting her own advocacy website to help other women who have been put under surveillance by their spouses.

"Sometimes it's really hard to have the courage to step out and get the help you need in that situation," she said.

Courser said he still feels guilty about what happened and has apologized to Gamrat and her family. He and his wife Fon are in counseling and are planning to stay together.