'The President's Daily Briefing': How the top secret intelligence document is put together

The 'PDB,' dating back decades, has been the focus of recent controversy.

Recent controversy over what President Donald Trump knew about U.S. intelligence has shed new light on how he -- or any president -- is briefed on top-secret information.

A military official has confirmed to ABC News that Russian intelligence officers offered to pay Taliban militants to kill American troops in Afghanistan over the past year, amid peace talks to end the 18-year war there.

Outraged members of Congress have been demanding answers about who knew what and when, and more important, was President Donald Trump briefed and if not, why.

The White House has denied a New York Times report the president was briefed in writing on the intelligence. The president's aides argue it was unverified and while they specifically say he wasn't told verbally, they have been vague about whether it was presented to him in written form, in what's called the President's Daily Brief.

Instead, administration officials have turned their ire toward leaks.

"When developing intelligence assessments, initial tactical reports often require additional collection and validation. In general, preliminary Force Protection information is shared throughout the national security community—and with U.S. allies—as part of our ongoing efforts to ensure the safety of coalition forces overseas," CIA Director Gina Haspel said in a statement. "Leaks compromise and disrupt the critical interagency work to collect, assess, and ascribe culpability."

Four former senior intelligence officials previously involved in assembling the "PDB" described to ABC News the delicate business of briefing a president and how the top-secret document is put together six days a week.

What is the Presidential Daily Brief?

Former Secretary of Defense and CIA Director under President Barack Obama, Leon Panetta, calls it "incredibly important."

"It's not a good way to start your day," Panetta told ABC News. "It can put a lot of worry into your head, by virtue of just reading about all the potential threats that the country is facing."

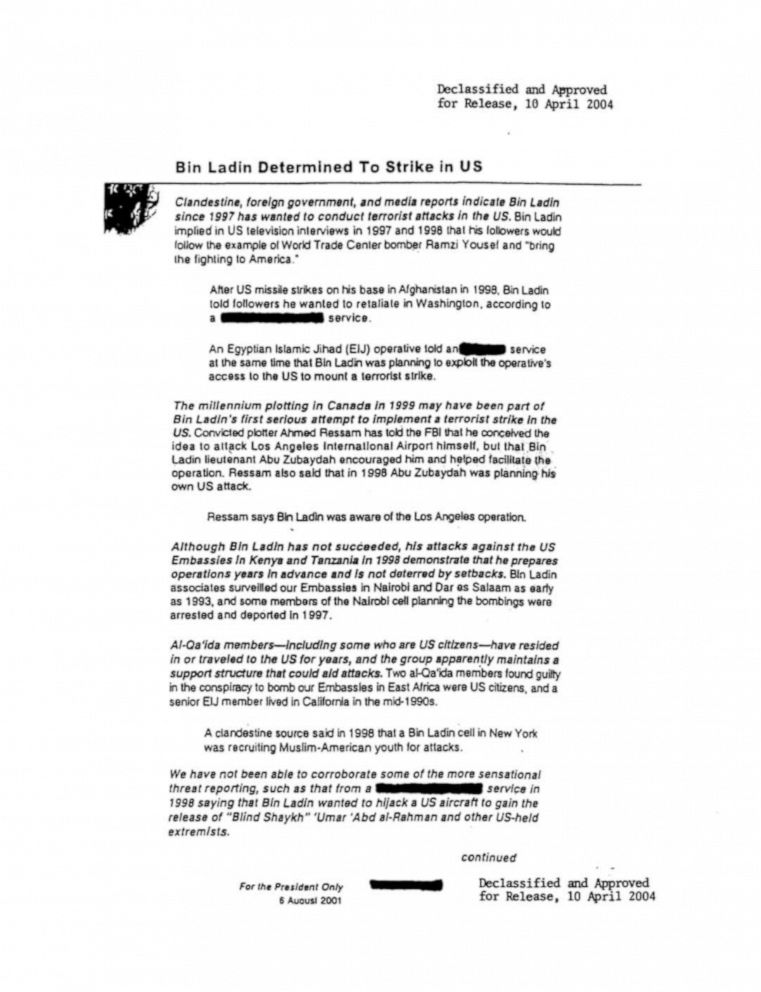

Perhaps the most famous PDB is the one made public by the 9/11 Commission in 2004. It's title: "Bin Ladin Determined To Strike In US."

The intelligence was shared with the then-President George W. Bush on Aug. 6, 2001, more than a month before the hijackers carried out the 9/11 attacks.

While it is rare for the public to see a PDB, the origins can be traced back to President John F. Kennedy, who wanted to be kept abreast on issues both foreign and domestic.

Bruce Riedel, a former national security official, told ABC News that even today, the PDB has the same goal it did in the 1960s.

"In the Kennedy administration it was called the President's intelligence checklist, or pickle," Riedel, now a senior fellow and director of the Brookings Intelligence Project, told ABC News. "It's purpose is really the same as it was back in the Kennedy administration -- to give the president a fairly short and concise summary of the most important intelligence."

He said the staff responsible for the PDB started out small, but now intelligence officers work around the clock to prepare the document.

Stephen B. Slick, a former CIA operations officer and member of the National Security Council, told ABC News that the PDB has only one person in mind.

"It is simply a brief compilation of the most important intelligence information and analysis that the IC believes should be shared with the president," Slick, now the director of the Intelligence Studies Project at the University of Texas at Austin, said.

"[Intelligence Community] agencies produce hundreds of reports and analytic products each day for customers across the U.S. national security establishment. The PDB is typically the pick of that crop prepared for the 'First Customer,' he said.

Slick said that the PDB is ultimately the responsibility of the director of National Intelligence, but that it is full of CIA information, "which drafts and coordinates most of the articles that run."

Javed Ali, a former national security official and member of the National Security Council, said that the PDB is supposed to bring together all the information available to top officials.

“Theoretically the PDB is supposed to be a cross-functional product,” Ali, a visiting professor at the University of Michigan, said. “It fuses different perspectives and intelligence reporting, and shouldn't just be one agency constantly informing the most senior officials about what's happening in the world.”

Each president is different, Slick stressed, and every president has his own style and manner in which they prefer to be briefed.

"JFK wanted a card to stick in his shirt pocket," Slick said, while Richard Nixon relied on Henry Kissinger to brief him, and "Obama received his PDB on a tablet computer."

Riedel said that "about a dozen or so" officials normally would see the PDB, from the vice president to the president's national security adviser to the White House chief of staff.

The PDB is put together by analysts who have specific expertise on various world issues or events, but determining what actually makes it into the PDB and what the president sees on a daily basis, is a challenge for intelligence officials.

Ali told ABC News that the threshold for what appears in the PDB is high and is often aligned to issues of interest to senior policymakers, while also leaving flexibility for topics identified at the "bottom-up" level or on late-breaking developments.

Riedel echoed that view, saying there are multiple levels -- from supervisors to the director of National intelligence -- that analysis goes through before being placed in the president's briefing book.

"It can be a process that takes a long time," he said.

Slick explained that what ends up in the actual briefing book can be wide-ranging.

"PDB "articles" can originate with the [intelligence community] based on new reporting or recently completed analysis that they believe merits the president's attention. Or, a PDB item can be a response to a question by the president, a senior principal or linked to a meeting, trip or decision he will shortly be required to make," he explained.

A personal briefing

In addition to a physical copy of the PDB, which Panetta said varies in page length based on the day and the intelligence, officials get an in-person briefer to answer their questions.

"A briefer will come in from the CIA and summarize the key elements of the PDB, respond to questions and if there are questions that the briefer doesn't know the answer to will usually come back with additional information," Panetta said.

Riedel said that when the president is briefed, the CIA director and director of National Intelligence are usually in the room.

In the Trump White House, Riedel said when now-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was CIA director, he knew how to get through to the president.

"My understanding is that Mike Pompeo was very good at this, when he was director. He understood how to read the president's mood, and understood how you could get information that the president would absorb, Not all the time. He had a pretty good track record on it," he explained, adding he has "no idea how it works in the current environment."

Not only is briefing the president "very demanding," Riedel said, but the president also serves as "your number one feedback. And if it's going right, the president and CIA analysts are more or less engaged in a dialogue."

Because former President Bill Clinton stayed up until all hours of the night, he'd receive the briefing in writing to start off with and would write questions in the margins of the PDB, Riedel said.

"First of all, someone would have to read his handwriting and make sense out of it, and then figure out what is this question about."

Bringing information to the president's attention

Panetta stressed any vital information about major adversaries such as Russia and China is always in the briefing book.

"Well, there's obviously a lot of judgment involved in what you're going to highlight, but I don't think there's any question that if there is intelligence in there that involves something serious involving our adversary that that would be highlighted," he said.

Panetta said that any intelligence, even not fully verified, about the Russians offering the Taliban a bounty on American soldiers would "absolutely" be something that the president should know about.

"Are you kidding me?" Panetta said. "The lives of our men and women in uniform, and they're being targeted and they're being killed, with a price under a head? There's just no question."

Panetta added that he would be "very surprised" if intelligence analysts didn't do their job.

Slick explained that the president might not have taken note and "the fact that IC experts may not have reached full consensus on the facts or implications of these reports would not keep it out of what he calls "the book."

Slick said that while it is fair to look at the actions of the president, Americans should also focus on the people around him.

"The national security adviser and secretary of defense in particular should have been laser-focused on this issue and keeping the president informed and supported," he said. "Any minimally competent national security adviser or chief of staff would sense the tactical, strategic and political implications of reports like this … and also should have foreseen that it would leak and generate controversy."

Ali said, in theory, someone else could have seen and acted on the same information.

“The DNI should have seen it. Other very senior customers who also get the PDB could have seen it and even started a process to bring the government together to confront that even if it didn't get to the President's attention.”

Panetta said that he doesn't know any intelligence official who wouldn't "speak truth to power when it comes to critical intelligence."

If they didn't brief the president on this matter, he added, "that's unacceptable."