States' election funding requests indicate numerous anticipated hurdles

Current federal filings give glimpses into states' focuses for 2020 voting

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has already thrown the 2020 primary season into disarray, but now with just over six months until November, the aftershocks of the spread of COVID-19 threaten to rock the general election, leaving states grappling with a slew of underlying logistical hurdles embedded in the administration of the voting process.

Filings submitted by states and territories to the U.S. Elections Assistance Commission as part of the CARES Act--a $2 trillion economic stimulus package President Donald Trump signed into law last month-- indicate that election officials are already scrambling to address inevitable changes ahead, but given the decentralized nature of U.S. elections, each state seems to be angling at different solutions to mitigate voting amid the pandemic.

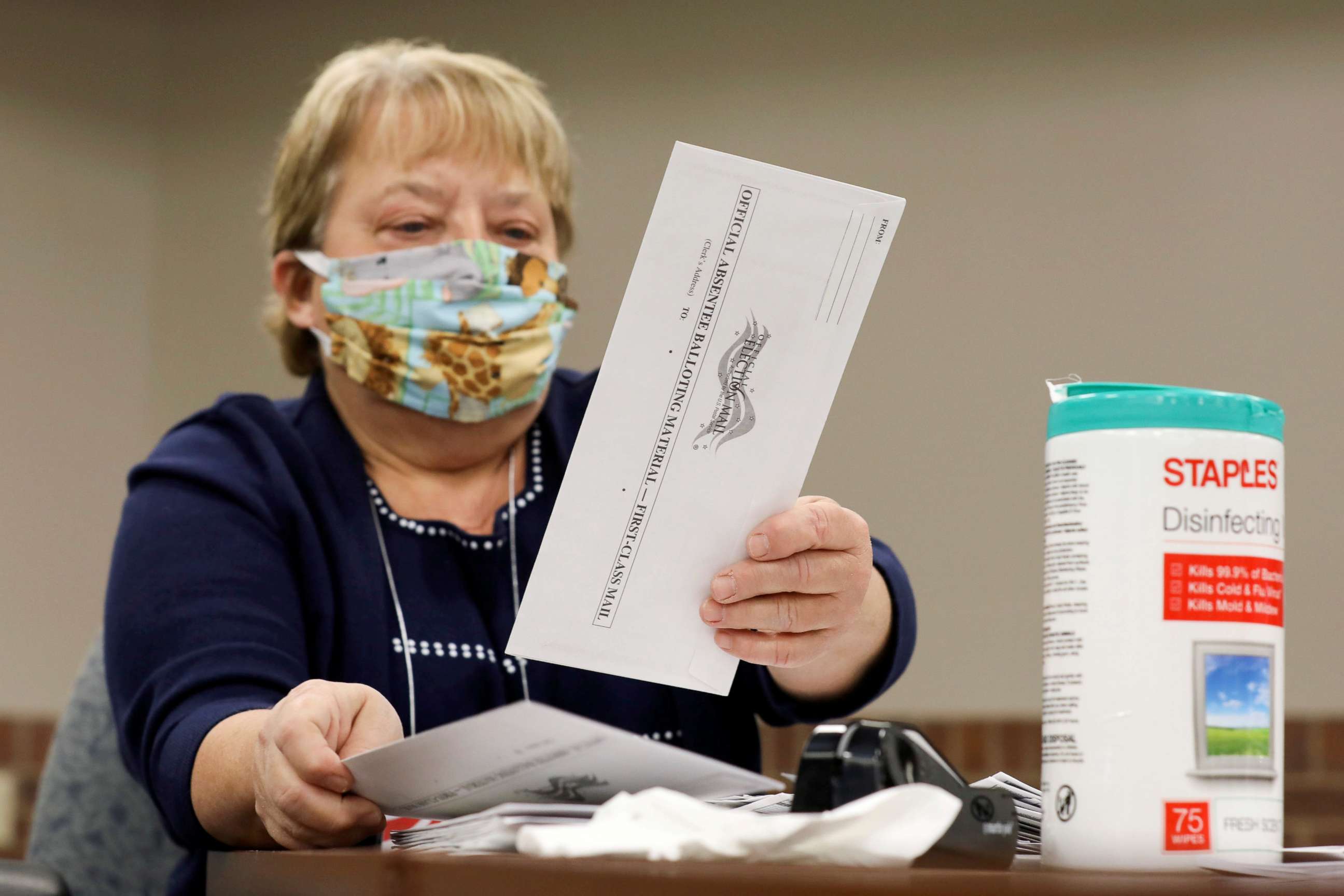

The outlined tactics include a myriad of issues including tangible solutions -- like using the funds to purchase cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment for poll workers -- to more nuanced endeavors, like bolstering vote-by-mail efforts and absentee voting procedures. Some states even specify plans to dedicate a portion of their granted funds to run communications campaigns aimed at educating Americans about any newly-implemented changes to the voting process.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

According to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, all 50 states submitted funding request letters for grants apportioned through the $400 million included in the Help America Vote Act, which was a component of the CARES Act. As of April 7, the Election Assistance Commission says it had “obligated 100% of the funds,” and as of April 20, it had “disbursed 75% to the states.” The funds are disbursed within four or five days of receiving a state’s request letter.

Although the current set of submitted request descriptions serve as broad outlines for how states may ultimately end up using the first tranche of funds, they also provide an early glimpse into which elements of the voting process states are currently examining ahead of November.

Most states show a focus on expanding voting methods

A review conducted by ABC News of requests submitted by states as of Tuesday to the Election Assistance Commission, indicates at least 32 states and the District of Columbia explicitly note a component of the received federal funding would in some way go toward bolstering either vote-by-mail efforts or absentee voting, which typically happens by mail.

The notion of strengthening the infrastructure to fund such methods seems to stretch across the country’s geopolitical regions, with states that are traditionally considered safely partisan grounds for both sides of the aisle echo similar priorities, despite Trump’s recent pushback on voting by mail.

“Mail ballots are a very dangerous thing for this country, because they're cheaters. They go and collect them. They're fraudulent in many cases,” Trump alleged at a press conference earlier this month, as a debate over the dangers of holding in-person voting amid the coronavirus pandemic seeped into the voting process of the Wisconsin primary election.

Election experts and secretaries of states where elections are conducted by mail voting largely disagree with the idea that mail ballots are more prone to tampering or fraud. Even so, the process of conducting an all-mail election presents a series of detailed steps.

During a panel discussion on the topic of holding elections in the time of the coronavirus pandemic hosted by the Center for American Progress earlier this month, Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold described the typical mail voting process in her state. Colorado is currently one of five states conducting all elections by mail, along with Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington.

Griswold said when mail ballots are returned in her state, they are delivered in sealed, tract boxes to county processing centers where they are opened by a bipartisan team of election judges and sorted into trays. After that, a different team of bipartisan election judges conducts signature comparisons on the ballots.

"If there are any discrepancies a voter is contacted, and if they do not cure those discrepancies, the ballot is actually referred to a district attorney for prosecution," Griswold said, adding that prosecution rates in Colorado are "extremely low."

Even so, election experts advise that states hoping to bolster similar methods need to be wary of the human error that often comes with first-time mail voters.

“If there's a public service announcement that I could do, it's that everybody who's going to vote by mail needs to read the instructions very carefully and follow those instructions to make sure that your ballot will be counted,” says Michael McDonald, an elections expert and political science professor at the University of Florida.

“You don't want to go through the whole process of requesting a ballot, filling it out, mailing it back in, only to have it rejected because you fail to do an important step in the process,” McDonald said in an interview with ABC News.

Some states already indicate a need to educate 2020 voters

In addition to failing to read instructions, McDonald says some voters make other “well meaning” errors like sending multiple ballots in one envelope from all members of a household.

The tribulations McDonald describes highlight the need for a strong voting communications infrastructure, which some states seem to already have on their to-do lists ahead of November based on initial funding requests sent to the Election Assistance Commission.

According to federal funding requests reviewed by ABC News, a handful of states -- including Illinois, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, Wyoming, West Virginia, as well as the District of Columbia -- noted that they would use some of the allocated funds to run communication campaigns aimed at voters in hopes of informing them about potential changes or updates in their states' respective voting processes.

Experts also note that a crucial component of administering effective voter communication would include informing people of any changes to the voter registration process well ahead of November.

“[States] are going to need to upgrade their voter registration systems so they can do online registration and so they can have remote access for people who can't access online voter registration [portals],” Wendy Weiser, a vice president and director at the Brennan Center for Justice Democracy Program told ABC News in an interview.

Three states, including California, Maryland, Wyoming, along with the District of Columbia, specifically mentioned using the funds to approach voter registration, at least in some capacity, in their federal funding requests.

McDonald said that a lagging focus on registration by states could also present an opportunity for political groups to fill the void, especially with people who are not currently registered voters. Groups who are unregistered in larger numbers tend to be younger people, people of color and people who tend to be on the lower end of the economic spectrum, according to McDonald.

“You're going to have the parties and campaigns act as backstops for what the election officials are doing,” he said.

Funding requests show polling places will still exist

Day-to-day lifestyle changes due to the coronavirus pandemic also loom large in ABC News' analysis of provided funding requests.

At the time of review by ABC News, least 32 states and two territories explicitly noted they would use the funds to purchase sanitizing materials or personal protective equipment, further indicating an expectation that in the months ahead, both voters and poll workers will be inclined to follow health safety measures that are currently in place.

Election experts agree that physical polling places will still need to exist regardless of current pandemic conditions in order to accommodate certain groups within the electorate, like people with disabilities.

“Some states were really adamant about the fact that you can't do away completely with in-person voting, I agree with that,” McDonald said.

Weiser also backed that sentiment, saying, “We're still going to have polling places, no matter what and we still need to have them.”

Still, these experts also note that states will likely face a myriad of adjustments as they proceed with administering the 2020 election, which will require election officials to address newfound safety concerns along the way. As medical experts contemplate the possibility of the virus’s resurgence closer to November, any unexpected hurdles could lead to a need for more funding.

The potential for additional costs looms large

The cost of holding a fully secure and safe presidential election amid a pandemic would run about five times more than the amount that has been disbursed so far. According to a March estimate calculated by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School, states would need an estimated total of $2 billion to adequately prepare, staff and organize the voting process in time for the November election.

Experts at the nonpartisan think tank warned that costs could balloon even more than their original estimates given updated safety guidance from health officials that calls on people to protect themselves and those around them by wearing masks.

“There's a range of other innovations that are happening right now that will add significantly to the cost of running the election that we did not cost out,” Weiser said, adding, “[The estimate] should be viewed as a floor, not as the entirety of it, but I think it was to add some real concreteness to the kinds of expenses that states were going to have.”

Weiser said states would need to factor in adjustments to virtually every step of administering the election process, including the actual counting and processing of individual ballots. Weiser argues that the current federal sum of $400 million distributed among states is not enough to “run a fair and credible election this November.”

“At the very least, we will see, you know, the kinds of problems we saw in Wisconsin play out across the country,” Weiser says.

The latest stimulus package signed by Trump on Thursday aims to help small businesses, hospitals and first responders, and bolstering nationwide coronavirus testing, and did not address further funding the election or election security. On Friday, House Speaker Pelosi said Democrats are moving ahead with crafting the next coronavirus relief package, which she says will aim to help states.

Earlier in the week, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer indicated that election funding was going to be among the top priorities for Democrats in the next round of negotiations, but as the legislative process inches along, experts say time is running out.

“[States] are going to run out of time at some point -- the printers that have said that if the orders don't come in by early summer -- and in some cases it's even earlier -- they're not going to be able to print those ballots on time by November,” Weiser says, “So it's, you know, it takes time.”