Why some civil liberties advocates worry about crackdown on 'misinformation'

Some fear the move will allow governments to stifle free speech.

Misinformation – false information spread regardless of intent – is rampant across popular social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook.

Most speech, whether true or false, is protected under the U.S. legal system.

But questions about inaccurate information, spread maliciously or not, and its effects on many facets of our lives have led to efforts by social media platforms, fact-checkers and others to try to crack down.

The territory is murky and has ignited an intense debate as technology companies struggle to define the problem and attempt to get a handle on the flood of false and misleading information.

In the U.S., the situation came to a head during the 2020 presidential election cycle when social media platforms decided to fact-check and remove election-related statements from former President Donald Trump and ultimately decided to suspend or ban him in the wake of the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol for tweets that ran counter to the company’s glorification of violence policy. Facebook later announced the suspension would be lifted in two years under certain conditions.

The move led to an outcry, largely from conservatives as well as civil libertarians about free speech and the rights of social media companies to regulate what has become what many consider the new public square.

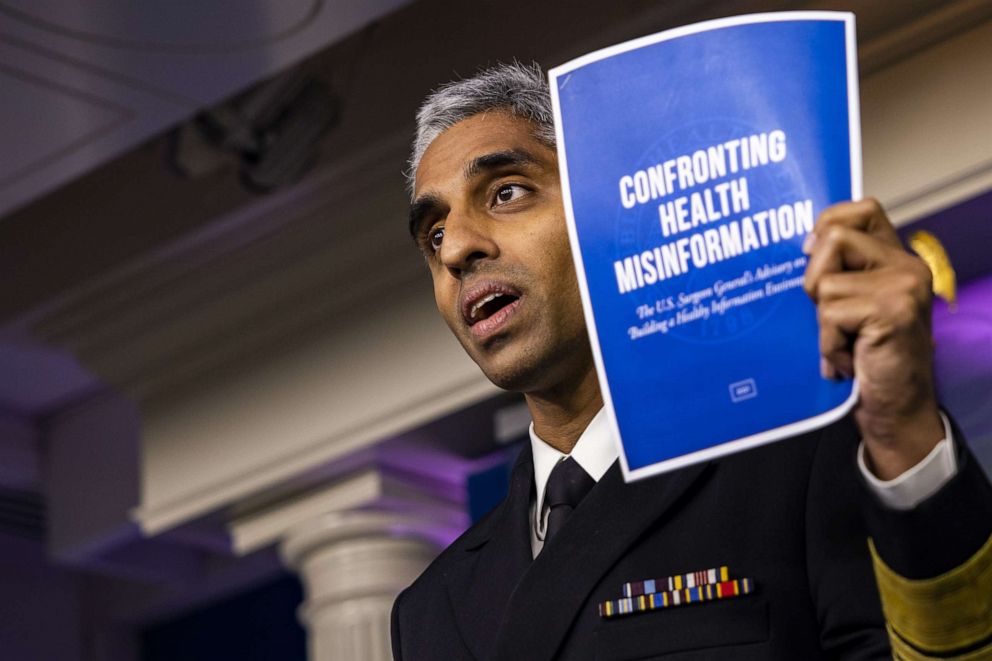

Misinformation has become such a crisis, in fact, that the U.S. surgeon general, Vivek Murthy, recently issued a warning about false information surrounding COVID-19 vaccines. And President Biden Friday said it was "killing people," a description Facebook took exception to.

Some governments, however, have taken steps to go even further, and there are fears of using the concept of misinformation broadly to target dissent.

In recent years, Singapore, for example, implemented a law that requires platforms to remove certain posts that go against “public interest” such as security threats or the public’s perception of the government.

Similarly, Russia can legally fine those who show “blatant disrespect” online toward the state.

India takes on misinformation

In February, India, the world’s largest democracy, implemented new rules to regulate online content, allowing the government to censor what it claims to be misinformation.

Under the rules, large social media companies must appoint Indian citizens to a compliance role, remove content within 36 hours of legal notice and also set up system to respond to complaints, according to Reuters.

These restrictions give the government more power, in some cases, to dictate what can and cannot be circulated on digital platforms in the country.

For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) said that the COVID-19 variant “B.1.617,” now known as delta, was first detected in India last year.

According to Reuters, in May 2021, the Indian government sent a letter to social media companies demanding that all content that names or implies “India Variant,” as it became commonly (but not officially) known, be removed from platforms, calling that moniker “FALSE.”

In another case, late last year, farmers in India clashed with police over new laws that they believe will exploit their practices and reduce income while giving power to large corporations. In February, the Indian government issued an emergency order that demanded Twitter remove posts from the platform that used the hashtag “#farmergenocide.”

The government said in a statement that while India values the freedom of speech, expression “is not absolute and subject to reasonable restrictions.”

A Twitter spokesperson said in a statement to ABC News that when a valid legal request is received, it is reviewed under both Twitter Rules and local law. Should the content violate Twitter’s rules, it may be removed from the platform.

“If it is determined to be illegal in a particular jurisdiction, but not in violation of the Twitter Rules, we may withhold access to the content in India only,” they continued. “In all cases, we notify the account holder directly so they’re aware that we’ve received a legal order pertaining to the account.”

Separately, WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, has sued the Indian government, which is looking to trace its users, who use encrypted messages. The government wants to have the ability to identify people who "credibly accused of wrong doing,” according to Reuters. Although the Indian government said it will respond to the lawsuit, it hasn’t done so yet.

Krishnesh Bapat, a legal fellow with the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), an Indian digital liberties organization that seeks to ensure technology respects fundamental rights, highlighted the implications of the WhatsApp case.

“This is one of the most problematic consequences of these rules,” Bapat said. “Several experts have suggested that the only way to implement this would be to remove encryption.”

End-to-end encryption is a key feature for WhatsApp users, as it protects private conversations from being accessed by any entity outside the chat. WhatsApp claims the new rules are unconstitutional and a clear breach to user privacy.

“India is a big cautionary tale for how we have to be really careful of the most well-intentioned regulatory power,” said David Greene, senior staff attorney and civil liberties director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). “We used to say, ‘well that's not a threat to democratic societies.’ I don't think we can say that anymore, India's a democratic society.”

ABC News could not immediately reach the IT Ministry for comment.

Difficulty in regulating

Platforms rely heavily on users flagging potentially harmful posts that break community guidelines, and that self-regulatory model may be the best bet for the future of content regulation, Greene said, as opposed to government or institutional regulation.

Similarly, A Yale Law review published earlier this year explains that a self-regulatory model should be considered to combat the spread of misinformation in India. The review says that implementing such a model should “ensure that the ‘outcomes-based’ code is not vague or tilted to serve state interests, and does not incentivize platforms to adopt an overly heavy approach to removing content. The outcomes should be built around common objectives, and should provide flexibility for platforms to develop protocols and technological tools to achieve them.”

The New York State Bar Association recently suggested that government policy and oversight can be just as important as a self-regulatory model when dealing with misinformation. It also mentions that combatting misinformation is not solely for one entity to address, claiming that it will require corporations, governments, educators and journalists to work together in an effort to prevent the continued spread of harmful, inaccurate information.

“Most democratic legal systems have robust free speech,” Greene said. “We find a lot of protection for false statements, and this is supposed to protect people because mistakes are inevitable. False statements have to actually cause a specific and direct harm before they’re actionable.”

This means that there must be a clear intent of defamation, written or spoken, in order for legal action to be taken, which is historically difficult to prove. In the U.S., libel laws in particular differ state to state, which adds an extra layer of complexity to any attempt at content regulation.

Greene also suggested that given the difficulty in casting information as verifiably false as well as the overwhelming number of posts that need to be reviewed, it’s nearly impossible for platforms to regulate content well.

In February 2018, the first Content Moderation & Removal at Scale conference was hosted by the Santa Clara University High Tech Law Institute. Experts and advocates gathered to “explore how internet companies operationalize the moderation and removal” of user-generated content. They developed what’s now known as the Santa Clara Principles.

The model, which is endorsed by EFF among other notable groups, provides three guiding principles for content moderators – being transparent about the numbers of people permanently suspended or banned, proper notice and reason for doing so and a “meaningful” appeals process.

Greene says that the Santa Clara Principles can be utilized as a guideline for companies in an effort to preserve basic human rights in content moderation. Alternatively, regulation that involves prescreening or filtering posts can have serious human rights implications, but although a post may include false information that contains offensive language appearing to hurt certain people or groups, it’s usually not illegal.

“By mandating filters, users are subjected to automated decision making and potentially harmful profiling,” Greene explained. “This has a chilling effect on speech and undermines the freedom to receive impartial information. When knowing to be censored, users change behavior or abstain from communicating freely.”