On 30th Anniversary of disability civil rights protest, advocates push for more

"I kind of feel like we've stepped backwards a bit": Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins

It was an unusually hot Monday in March and the cherry blossoms had already bloomed in Washington, D.C. A group of protesters, advocates and a few politicians had gathered at the bottom of the steps of the Capitol building, as a man was finishing a speech about disability civil rights, asking Congress to pass a law -- the Americans with Disability Act.

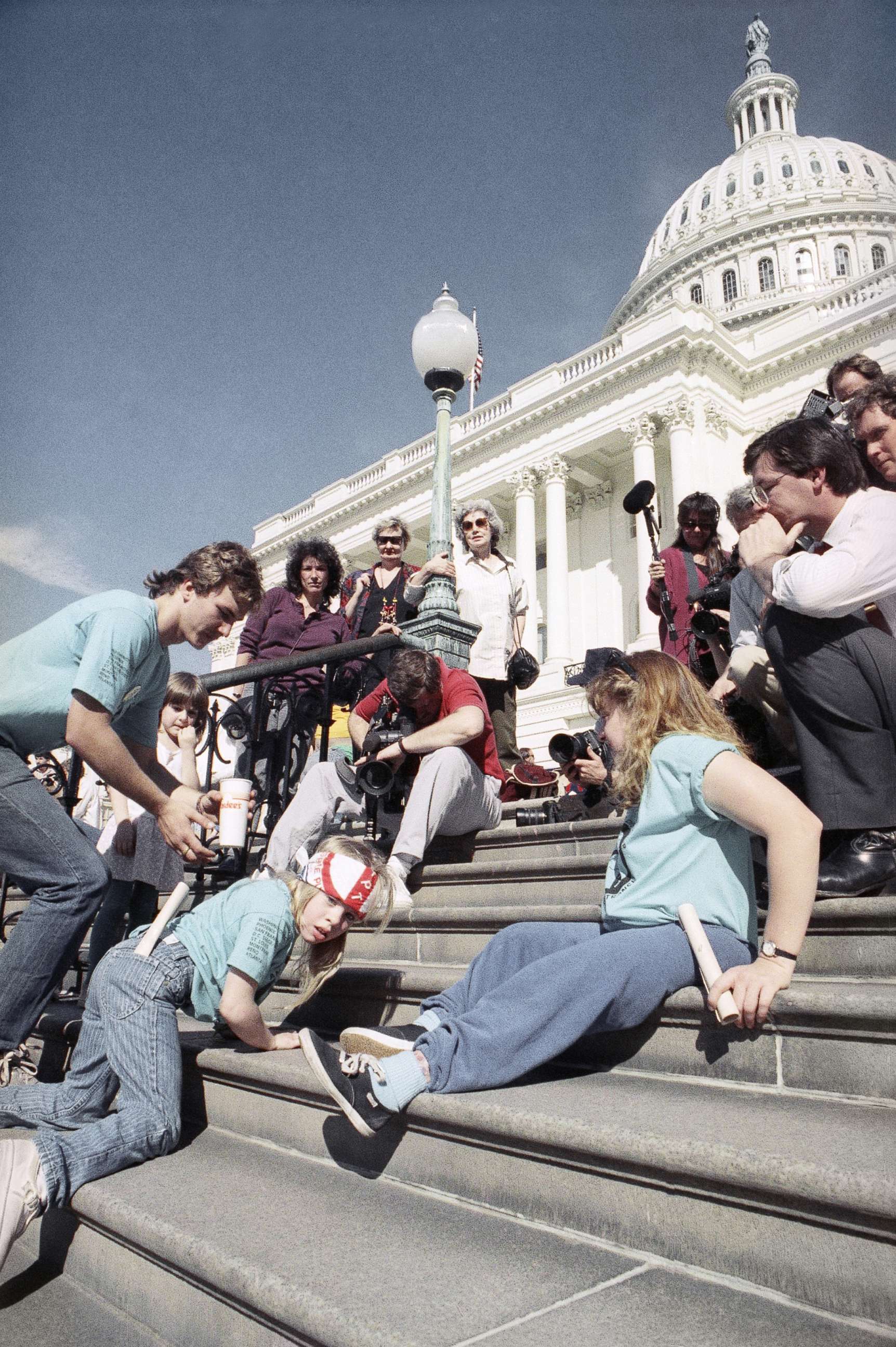

The moment the speech finished, March 12, 1990, protesters -- some sitting in wheelchairs and others leaning on crutches -- abandoned their assistive devices and began climbing the 78 marble steps up the Capitol's West Front.

Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins got on all fours to begin the ascent. Just 8 years old at the time with cerebral palsy, the climb up the stairs took almost an hour. But she was determined.

"As a matter of fact, I said, 'I'll take all night if I have to,'" Keelan-Chaffins told ABC News about that day.

Over 61 million Americans – or 26% of adults in the United States -- live with some type of disability, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Through the efforts of activists like those who ascended the Capitol's steps decades ago, the Americans with Disability Act prohibits discrimination based on a disability, legally ensuring people with a disability "have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else."

"The ADA has really changed the face of America in so many ways," said Marilyn Golden, the Senior Policy Analyst at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund. "It covers employment, it covers public accommodations -- which are privately operated facilities open to the public, like hotels and restaurants and doctors' offices, and you know, gas stations."

But just 30 years ago, these civil rights didn't exist for people living with a disability.

Looking back on that day, Keelan-Chaffins said she can still remember the noise.

"As I got further and further up the steps, once people realized that I was actually climbing and participating in the Capitol Crawl, all I could hear was this humongous roar of cheering," Keelan-Chaffins said. "Of people cheering me on, telling me that I can -- that I'll be able to make it. That I can, you know, just take one step at a time."

She said she had to stop climbing multiple times to ask for water. But toward the end, there were so many people willing to help.

"They were getting water whichever way they could," she said. "Every time I asked for water I had 50 cups to choose from."

That day is now known as the Capitol Crawl, and it's recognized as the catalyst to the passage of the Americans with Disability Act, which was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990. The group that organized the event was the American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today, also known as ADAPT.

"It was a very important part of the history of the disability rights movement," said Cynthia Keelan, Jennifer's mother, adding that she believes it deserves recognition.

But the Capitol Crawl protest wasn't the only disability rights protest -- in fact, people had been protesting for disability civil rights for decades. Jennifer herself had been protesting for two years – starting at the age of six.

She had protested in San Francisco, Phoenix, St. Louis, Atlanta, Denver and Montreal, Canada, – where she was arrested at the age of seven. Keelan-Chaffins told ABC News that she had crossed a specific protesting line while trying to reach the women's restroom, and the police mistakenly arrested her.

But 30 years later, the Capitol Crawl is going unrecognized. ABC News reached out to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other leading members of Congress who are disability rights advocates, but has yet to hear of a single office recognizing the event.

"In some ways, I kind of feel like we've stepped backwards a bit," Keelan-Chaffins told ABC News, later adding "even though, you know, the ADA has granted greater access -- physical access to people with disabilities, I honestly don't believe that the ADA has solved every aspect of discrimination or discriminatory behavior that we still face today."

Less than three weeks ago, Keelan-Chaffins said she went with her mother to a local pizza joint in Denver, Colorado. But upon entering the restaurant, the tables and chairs were so densely packed she couldn't move into the space – the restaurant was not ADA compliant. She and her mom ended up eating their pizza outside in the middle of winter.

"This isn't just about, you know, having a handicap parking sticker and, you know, having a curb-out here and there, you know, and maybe being able to use RTD (Regional Transportation District) on occasion," said Keelan-Chaffins' mom. "This is about a civil right."

Both she and her mom said they've been noticing less and less ADA features in new buildings, and Cynthia Keelan says she thinks a lot of people "just kind of feel like they don't have to comply anymore."

Marilyn Golden, of DREDF, agrees, saying the ADA is great, but the problem is that people are no longer complying, especially on the local level. Golden points to housing, which is covered by the Fair Housing Act, as a major issue.

"Multi-family housing has to meet a certain principle of acceptable design," Golden said, giving examples like wheelchair-accessible entrances and hallways being a certain width. But Golden says many new buildings aren't meeting these standards, and no one is regulating them either.

But Jennifer is hoping for change – her experience is the subject of a new children's book, which promotes inclusivity and positivity.

"Even though I was only eight, and even though I was, I was quite young, I knew that I had a great responsibility to represent young children – of my generation and future generations of kids with disabilities -- because I knew that, how important it was, for not just me to be represented, but for them to be represented," Keelan-Chaffins said. "And so that's why I took my participation in the disability rights movement so seriously, because I knew that it wasn't just about myself, but it was about others. And it was about the future generations of children that would come after me."