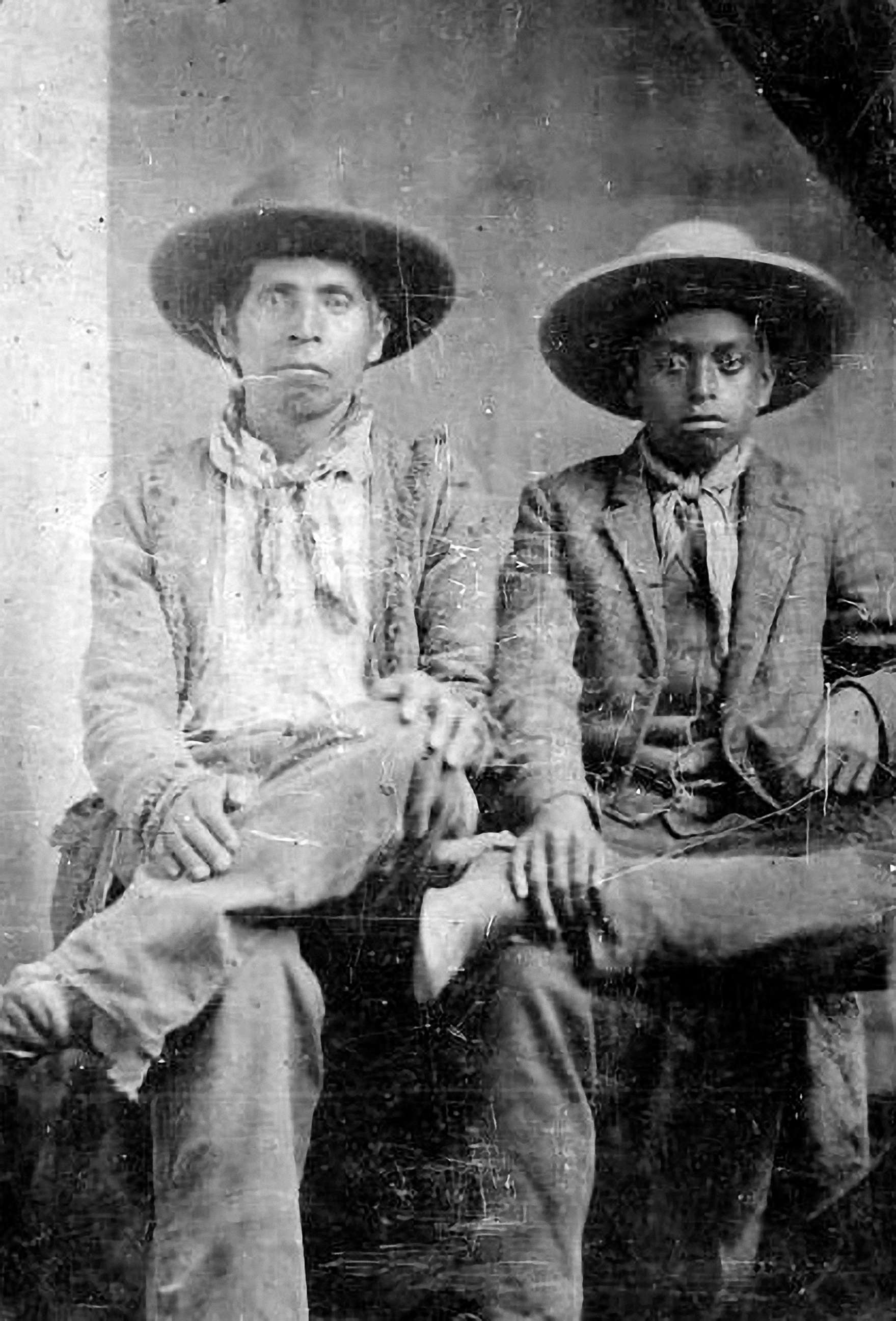

Black, Hispanic riding clubs keep cowboy identity alive after centuries of 'whitewashing'

Experts blame Hollywood for promoting a false history of cowboy culture.

The cowboy culture of Hollywood is not the cowboy culture of America -- the thousands of Black, Hispanic and Indigenous cowboys and cowgirls living in ranches and participating in rodeos across the nation can attest to that. Over the years, the true history of cowboys has been whitewashed, and only a handful of riding clubs are keeping it alive.

The members of Circle L 5, the oldest Black riding club in Texas, have been living the cowboy lifestyle since the club was founded in Fort Worth in 1951, and despite the racism and prejudice they have encountered over the years, Marcellous "Mo" Anderson, the club's president, told ABC News that "anyone who wants to ride, is welcome to ride" on their turf.

The history of the cowboy

What Wild West movies don't show is that African Americans have always been an integral part of cowboy culture. Some experts have even argued that the term "cowboy" was first used exclusively to describe Blacks, as white owners often referred to Black slaves as "boys" -- a derogatory term.

It all started in the 1500s, when Spanish "conquistadores" arrived in Mexico and began building ranches to raise cattle and other livestock. The men who herded the cattle on horseback were called "vaqueros," or cow men. The custom caught on in Africa, Europe and the Americas.

The social hierarchy that existed between the Spanish and the Indigenous in Mexico translated into slavery in the U.S., where Black men and women served as cowhands, hazers, cow ropers, wranglers, bulldoggers, broncobusters, drovers, cattle rustlers and brand readers for their white owners. Many white settlers even requested slaves from the Gambia River area of Africa, as they were valued for their knowledge and ability to handle cattle.

For slaves, there was more dignity and freedom in being a cowboy than in being a plantation or field worker. Still, it wasn't until slavery was abolished, in 1865, that the white men they once "belonged" to began hiring them to continue doing ranch work, as their skills on horseback proved invaluable. By that point, many had become well-respected in cowboy circles.

Still, cowboys were notoriously underpaid. The average wage for a white American cowboy between 1880 and 1930 was $1 per day, Michael Grauer, curator of cowboy culture at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma, told ABC News. Blacks made slightly less and Hispanics even less.

Cowboys and race

Anderson's view on racial equality on the ranch is echoed by cowboys of all races. It's a view which goes back to the very beginning of American cowboy history, when groups of men on horseback would take months-long trail drives from their hometowns -- usually in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, California, North Dakota or South Dakota -- to connect with Midwestern railroads, herding their cattle along the way. The journeys were long and dangerous, and whether you were Black, white or Mexican, you slept in the same spaces, ate the same food, performed the same tasks and took the same risks. The job left no room for racial prejudice, and those who survived the journeys formed bonds that would last a lifetime.

After the Civil War, 20% to 25% of cowboys were Black, Indigenous and Mexican, depending on geography.

"Along the Rio Grande, you had Tejanos and Hispanic people who were American," said Grauer. "In shorter trail drives around Houston, they were all Black. From South Texas to San Antonio, they were Hispanic. The farther north you got, the whiter they got."

Today, trail drives are still popular, but mostly as entertainment for riding club members and cowboy families.

Race and gender in equestrian sports

While racism has not been as prominent in the cowboy world as it has in other circles, the economic and cultural differences between Blacks and whites -- which come from years of racial inequality and white privilege -- are most of the reasons why Blacks are still not making headlines at rodeos or winning big awards in equestrian sports.

Brittaney "Britt Brat" Logan, 33, a former member of Cowgirls of Color and a current rodeo competitor, said African Americans have not had the same opportunities as whites in equestrian sports. While many white horseback riders belong to exclusive clubs, are trained in English riding, own $100,000 thoroughbreds and get sponsored by big companies, most Black riders go through "rough training" and don't have the backing or the funds to compete against their white counterparts.

"We have $15,000 horses that we trained from the ground up. We don't have formal training, so when we go to these activities, we are looked down upon," Logan said. "We also started late because of the exposure. We didn't know about this. We started from a very low point."

Still, she said more and more riding clubs for people of color are opening up, and kids and adults who had never been exposed to the world of cowboys, rodeo and horseback riding are joining.

Similarly, more rodeo shows are opening their doors to diversity -- both in race and in gender.

"Black women are still not winning at the level as white women in American rodeo, but we're coming, I promise you that," Logan said. "I don't think [white cowgirls] are better, but they had a better start, better equipment, better finances, exposure, help, sponsorship. But, again, it's coming. And what is inspiring for me is, 'I can compete at your level and I didn't start where you started.'"

Cowgirls have just as long a history as cowboys in America. Women were often the ones who raised the cattle and horses when their husbands were off on trail drives. Many of them were also great riders, but either hid their skills for fear of seeming too masculine, or hid their gender -- by dressing up as men -- to join crews of cowboys on their drives. They became more noticeable on ranches during World War II, when there was a shortage of men to work the livestock, but may did that work unpaid.

Cowboys and rodeo

Another reason why Black men and women have been late to enter the world of equestrian sports is because for centuries African Americans were not allowed to own horses. Grauer, the museum curator, said it was a question of hierarchy. Because Blacks on horseback were physically higher up than their white owners on the ground, the owners needed another way to exert their power. So, for many years, enslaved Black cowboys had to get written permission to ride a horse.

That same prejudice carried into rodeo and other equestrian competitions, in which whites discouraged Blacks from participating. Because of the exclusion, minorities created "Soul Circuits" in which they could compete against each other. The riders were called "Shadow Riders" because they participated in rodeo competitions in the shadows of their white counterparts.

Rodeo recently has gotten popular again, and according to "Black Cowboys in the American West," about 23 million fans attend Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association-sanctioned rodeos annually. There are many smaller rodeos at which attendance figures aren't known or reported.

Except for baseball, there is perhaps no other American sport seen as epitomizing so many American values and traditions -- and yet, like the nation itself, it has long overlooked the minorities who helped build it.

Today, Black cowboys have organizations like the Southwestern Colored Cowboys Association and the National Cowboys of Color Museum Hall of Fame to keep the history of their people alive. They also have various rodeos, parades and competitions in which longtime cowboys like those at Circle L 5 often participate. These include Cowboys of Color Rodeo, Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, Cowtown Rodeo in New Jersey, Southwestern Exposition, Fat Stock Show, Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo, All-Western Parade, Fourth of July Parade and Juneteenth Festival, among many others.

More ethnic rodeos are held on Juneteenth that on any other single day of the year.

The biggest rodeos, like the International Finals Rodeo, are still lacking Blacks, Hispanics and women, as is the Rodeo Hall of Fame.

"I blame Hollywood," Grauer said. "It's like Harvey Weinstein but for the whitewashing of the cowboy. Not that it comes down to one particular person, but it was Hollywood that did that."

Today, it is riding clubs like Circle L 5, Cowgirls of Color, Compton Cowboys and Las Vaqueras, that teach riders of color how to raise, maintain, ride and train horses. Similarly, organizations like the STAND foundation, founded by a former Cowgirls of Color member, are bringing equestrian sports to underprivileged communities.

"All of us down here know whats going on in the world, but once we get down here we try to leave political stuff outside the gates," Anderson said, referring to the recent Black Lives Matter protests. "We discuss it and we teach our riders about [Black cowboy history], but it always goes back to horses."

"Cowboyhood has always been about brotherhood, sisterhood and a love of horses. There are no political implications," said Tammy Sanders, whose parents own the ranch where Circle L 5 keeps its 40 to 50 horses. "But as African Americans, we need more organizations like Circle L 5 who create a positive reputation within the Black community."

Despite belonging to a community that has been so under-represented for so long, these Black cowboys and cowgirls refuse to focus on oppression. They see ample fields, rodeo trophies, family traditions and strong horses.