COVID devastated New York, but here's why it fared better in fall surge

Experts say most New Yorkers took pandemic seriously and followed guidelines.

New York was the early epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S., with hundreds of deaths a day during the spring peak.

It still has the second highest death toll for a state in the country, at more than 47,000 and the second highest per capita death toll.

But following a dramatic reduction in cases and fewer fatalities over the summer, the state avoided a dramatic surge in deaths during the fall and winter, unlike California, for instance, which now has the highest death toll in the nation.

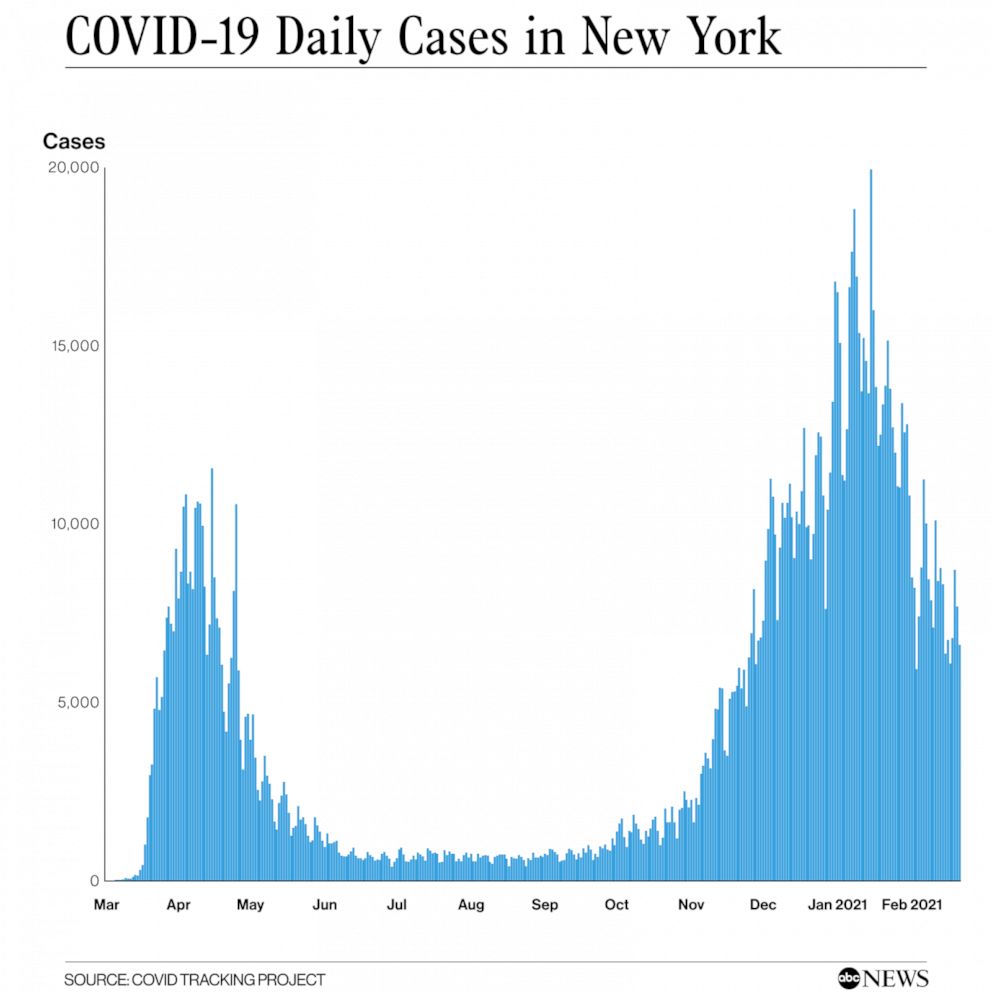

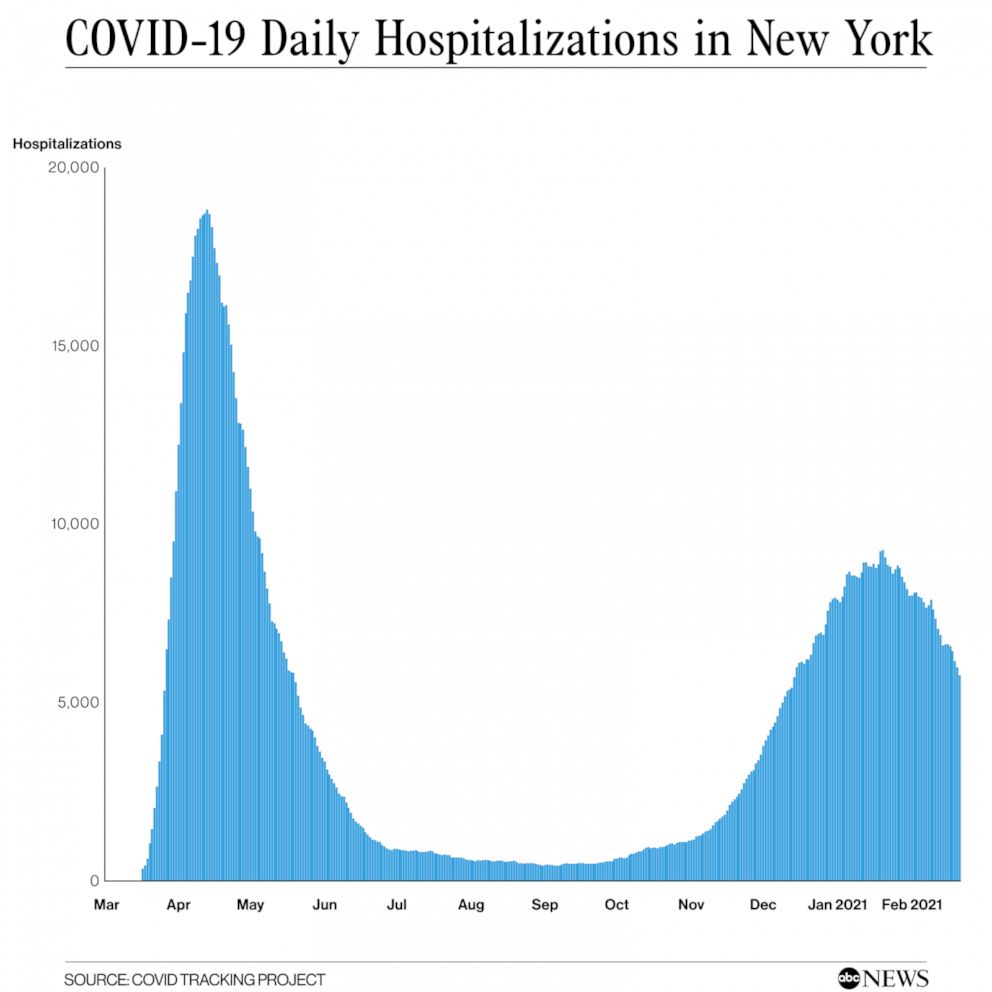

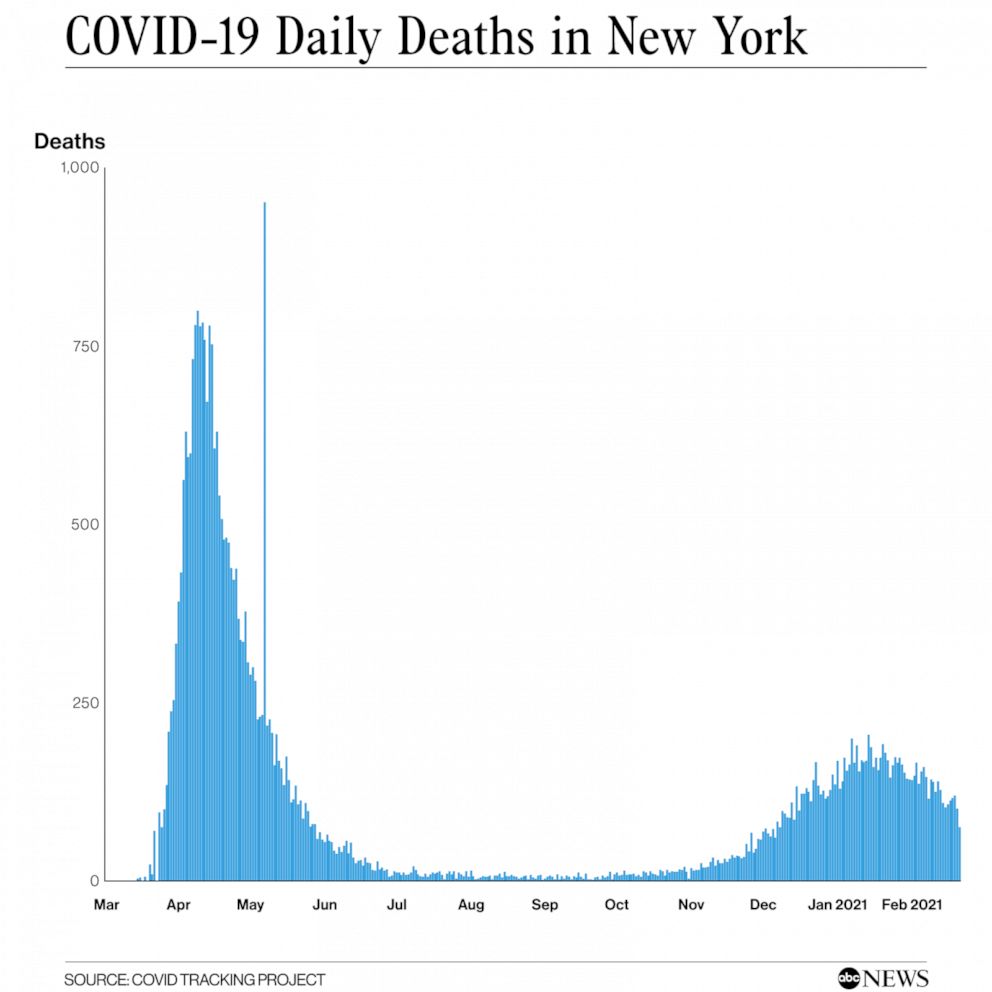

By the middle of April, the seven-day average for daily cases and deaths in New York was as high as 10,000 and 1,000 respectively with a peak of 18,000 people hospitalized, according to health data. By August, New York State turned things around and saw seven-day averages drop to as low as 600 new cases a day and seven deaths a day and hospitalizations at around 425 by the summer, according to health data.

Public health experts say there were many factors behind New York's recovery, including policies that restricted gatherings and pushed mask wearing, but the decisive element in the state's turnaround was the actions of its people.

"By and large the people of the state did a great job flattening the curve," Dr. David Larsen, an epidemiologist and associate professor of public health at Syracuse University, told ABC News. "People were willing to wear masks and take the virus seriously and that led to the drop in the summer."

With the state rolling out vaccinations and easing back on certain restrictions due to another drop in cases, Larsen and other experts said New Yorkers need to maintain their vigilance to ensure that the state stays on the right path.

Larsen said unlike other parts of the country, there was very little doubt among New Yorkers that COVID-19 was a real threat, particularly residents of New York City, where most of the early cases and deaths emerged.

"The damage caused was palpable. People know others who had it, who died from it, who were on ventilators," he said. "There was a reality to New Yorkers."

An early change in behavior

Troy Tassier, an associate professor of economics at Fordham University who has been studying epidemiology trends, told ABC News that public data indicates that New Yorkers were changing their habits long before the state shut down on March 22, 2020.

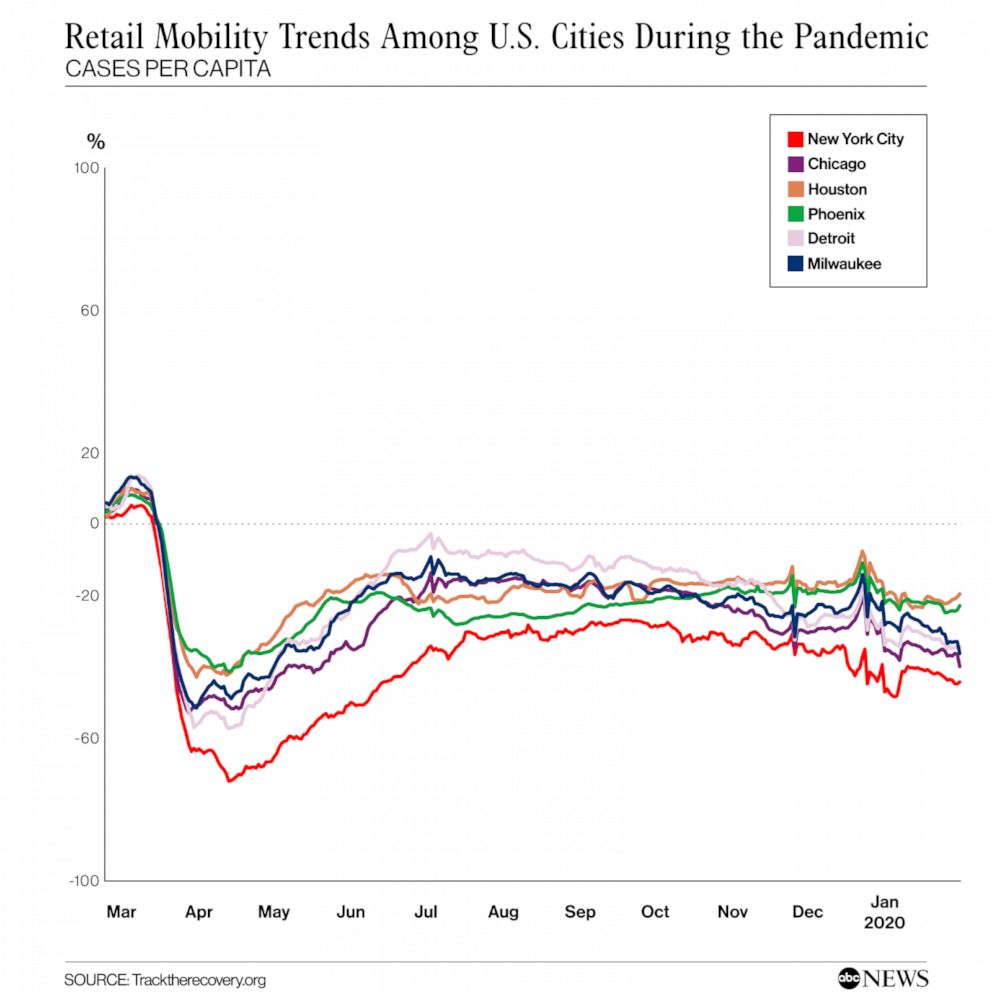

Tassier used the metro area mobility data based on cellphone records and found that levels in New York stores began to tail off at the end of February compared to the same period in 2019. New York still has not seen retail mobility rebound to pre-pandemic levels. However, there were some increases during the spring and summer months when cases subsided, according to Tassier.

In cities like Houston and Milwaukee, however, mobility levels saw bigger jumps during the summer and Tassier said that correlated with increases in COVID-19 cases in those locations.

Between June and July, Houston saw its seven-day average of new daily cases jump from under 200 to nearly 1,000 while Milwaukee's seven-day average jumped from around 100 to 200, according to data from both cities' respective health departments.

"We saw what happened in the spring and didn't want to live with that again," he said of New Yorkers. "The fear that happened in the spring provided us with extra incentive for mask wearing and social distance in the coming months."

Tassier and other health experts said constant and detailed communication from New York's elected officials and health experts informed their actions. Gov. Andrew Cuomo's daily news conferences along with the state health commissioner Howard Zucker kept New Yorkers on top of the situation and, at the time, was more transparent than other elected officials in the country, according to Larsen.

But recent admissions by the governor that he did not disclose the accurate number of COVID-19 deaths related to nursing homes have led to an investigation by the FBI and calls from state leaders to curtail Cuomo's emergency powers.

During a news conference on Feb. 15, the governor said the nursing home death count was a difference of "categorization" because those patients were counted as hospital deaths, but admitted the state should have done a better job at informing the public.

"No excuses: I accept responsibility for that," he said at the news conference.

Christina Greer, an assistant professor of political science at Fordham University, told ABC News that while the revelations may have diminished the public's trust in Cuomo, she does not believe that New Yorkers will all of a sudden change their attitude toward pandemic precautions.

"We have a health commissioner who believes in science and that's huge," she told ABC News. "I do think we have, compared to other states, more hospitals that are up and running and have more capacity. They're interested in educating people as well as treating people."

Tassier agreed.

"Gov. Cuomo isn't the only one giving this message [of increased vigilance]," he said. "Even if we lose faith in him ... other public health officials are saying the same thing."

Looking to the future

Tassier warned that New York could see another jump in cases and hospitalizations due to the variants in the virus that have been reported around the world.

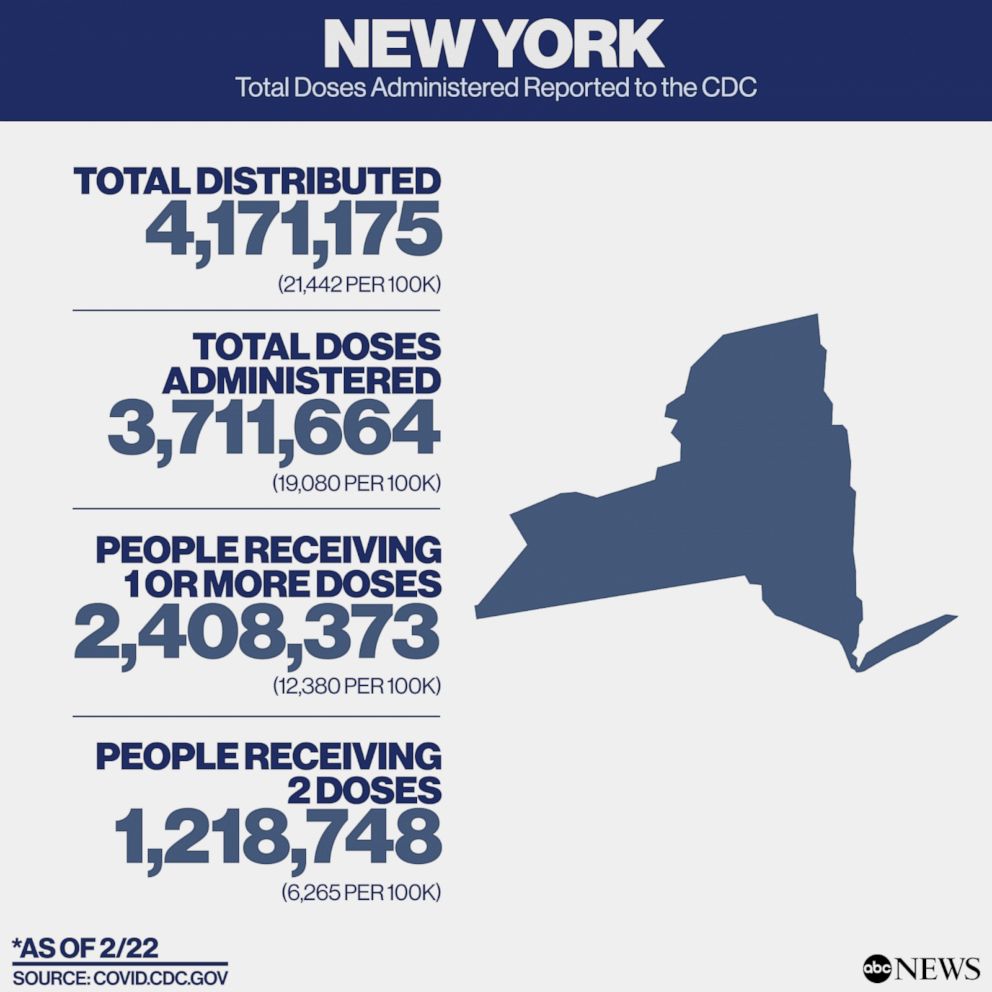

As of Feb. 22, 4.1 million New York state residents, roughly 12% of the population, have received a coronavirus vaccine dose, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Florida, Texas and California were the only states that administered more shots, according to the CDC.

Appointments across the state continue to fill up fast as more come online.

The vaccine rollout comes as the state eases up COVID-19 restrictions.

On Presidents' Day weekend, Cuomo allowed indoor dining to continue in New York City with limited capacity. Indoor sporting events reopened on Feb. 23 and movie theaters are slated to reopen with limited capacity on March 5.

Larsen said he doesn't think reopening indoor dining was the correct move since the transmission rate is still high and the variants pose a major risk; however, he believes eaters can evaluate the risk before choosing to dine at a restaurant.

"Even with that 25% capacity, if someone walks into a restaurant and they see people eating … will they want to go with it?" he said. "They may not feel comfortable in that setting."

Tassier said he's cautiously optimistic that New Yorkers will stay the course and mitigate any future jumps in cases in the spring or summer, as the fear from last year's outbreak is still strong and residents are willing to work hard to make sure it doesn't happen again.

"As long as everyone stays on message about wearing masks and maintaining social distancing guidelines we should be fine," he said. "Those are the most important things that New Yorkers need to follow."