Dramatic satellite images show how much water levels in Lake Mead have receded since 2000

Water levels at the largest reservoir in the U.S. are getting dangerously low.

Dramatic before-and-after photos of Lake Mead are providing visual evidence to the alarming rate in which the water levels at the largest reservoir in the country are receding.

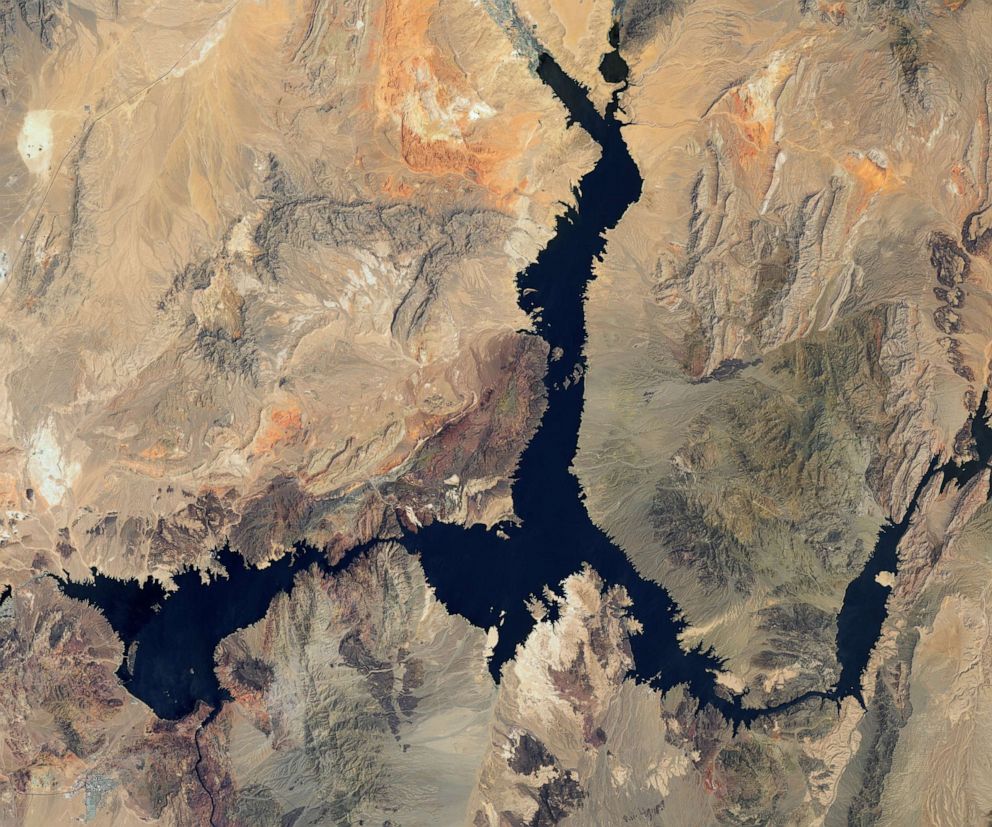

Satellite images released by NASA show side-by-side comparisons of Lake Mead, one taken on July 6, 2000, and the other more than two decades later on July 6 of this year.

The images show waterways that have thinned drastically over the past 22 years as the surface of Lake Mead continues to hit its lowest levels since it was created in the 1930s amid a decadeslong megadrought in the West, which is intensifying and expanding. The light-colored fringes along the shorelines in the present-day photos is the phenomenon known as the "bathtub ring" due to the mineralized areas of the lakeshore that were formally under water.

In June 2021, Lake Mead's surface elevation dipped to 1,071.48 feet, the lowest in recorded history at the time. In August of that year, the first-ever water shortage was declared for Lake Make, prompting mandated water releases to Arizona, Nevada and Mexico in 2022 in an effort to keep generating power and providing water for essential uses.

Now, water levels in the reservoir are so low they could soon hit "dead pool" status, in which the water is too low to flow downstream to the dam.

The minimum surface elevation needed to generate power at the Hoover Dam is 1,050 feet, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Anything below that is considered an "inactive pool," and a "dead pool" exists at 895 feet in elevation.

The water levels at Lake Mead measured at 1043.82 on June 23 and remained at 1040.75 on Sunday, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation -- a mere 146 feet away from becoming a dead pool. As of July 18, Lake Mead was only at 27% capacity, according to NASA.

The highest surface elevation ever in Lake Mead was in June 1983, when levels were recorded at 1,225.85 feet, according to data from the Bureau of Reclamation. The reservoir also approached maximum capacity in the summer of 1999, according to NASA.

Lake Mead has lost more than 25 feet this year alone, data shows. The water has receded so much that it has revealed multiple human bodies, some that may have been dumped there, as well as a World War II-era boat.

Water levels are expected to continue to dry up until November, when the wet season begins.

Much of the megadrought and the concern over a potential water shortage is attributed to climate change, as global temperatures increase, causing less snow to fall in the winters and therefore less water flowing into the Colorado River once spring arrives year after year. About 10% of the water in Lake Mead comes from local precipitation and groundwater, and the rest comes from snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains that flows down the Colorado River and to Lake Powell, the second-largest reservoir in the U.S., Glen Canyon and the Grand Canyon.

More than 74% of the Western U.S. is experiencing drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Lake Mead, which is part of the Colorado River watershed, provides water to 40 million residents in the Southwest. Levels at the reservoir are projected to hit a level that could require additional cuts in July 2023, as well as another 25-foot drop in the next 14 months, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

Global warming has exacerbated the megadrought so much that the current 22-year drought could have been reduced to just seven years without the interference of human-caused climate change, Matthew Lachniet, a professor of Geology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, told ABC News Chief Meteorologist Ginger Zee.

"The scientists have been warning about this for a very long time," Lachniet said. "We feel it's time for the policy to catch up."