Expected surge in virus that can paralyze kids didn’t happen, baffling experts

Expected outbreak of acute flaccid myelitis never occurred, for reasons unknown.

This is a MedPage Today story.

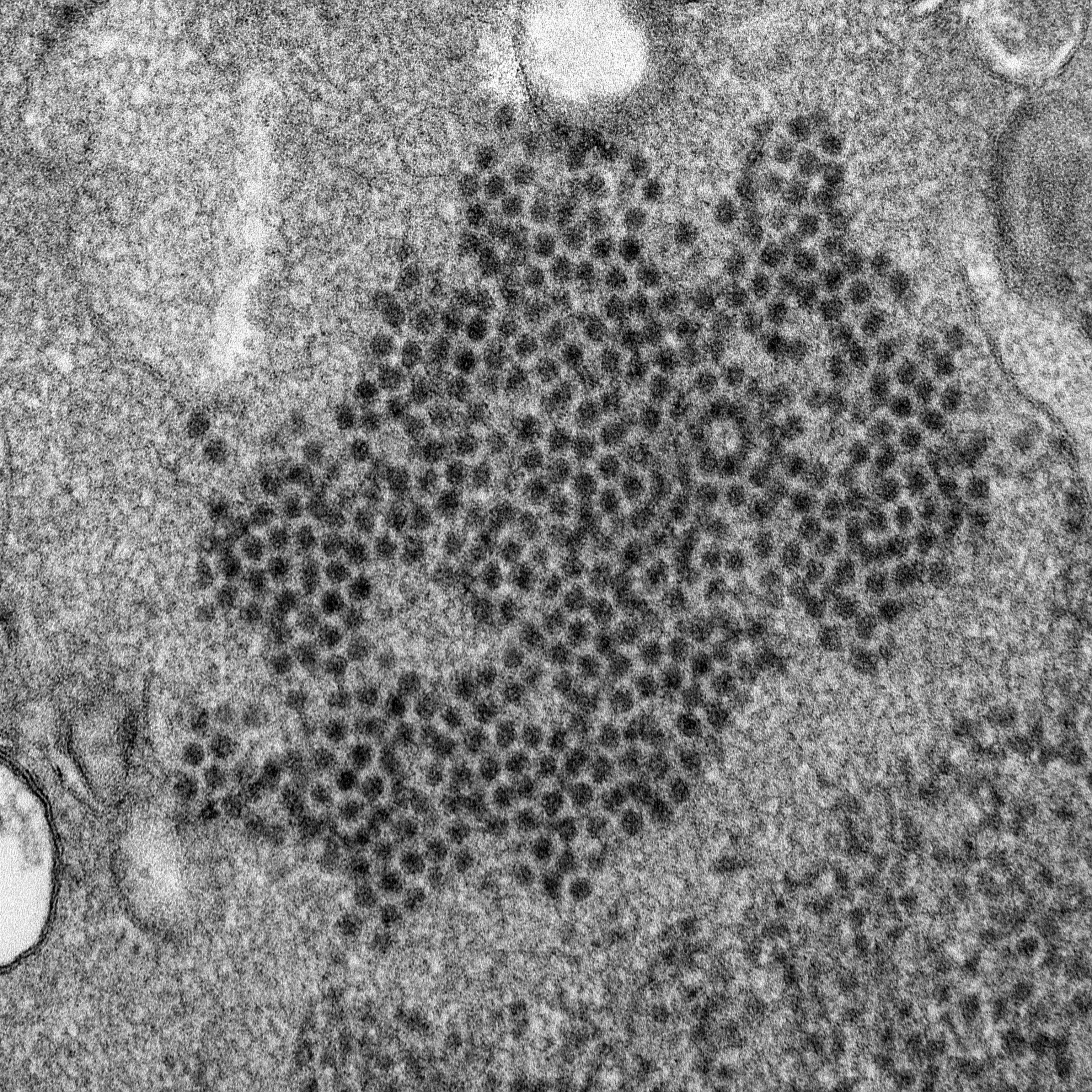

In September, MedPage Today reported on an increase of enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) cases among U.S. children, which has been linked to a rare neurological condition that can cause polio-like paralysis in children. In this report, we follow up on what has happened since those initial reports.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sounded the alarm on EV-D68 with a Health Alert Network Advisory in September announcing that cases were on the rise.

Later that month, the agency reported surveillance data showing that rhinovirus, enterovirus, or both were detected in 26.4% of children and adolescents with acute respiratory illness seeking emergency care or requiring hospitalization. Of these, 260 (17.4%) tested positive for EV-D68, and that rate climbed to 56% by mid-August.

Of gravest concern was the threat of potential acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), a rare condition associated with EV-D68 that affects the central nervous system predominantly in children, causing muscles and reflexes to become weak and potentially leading to paralysis. Previous outbreaks of AFM had spiked in even-numbered years (2014, 2016, and 2018).

However, as of December 1, 2022, the CDC reported that AFM had not surged as expected.

"AFM cases have remained low in 2022, despite an uptick in enterovirus D68 circulation and infections," said Dr. Janell Routh, who leads the AFM and domestic polio team for the CDC's Division of Viral Diseases.

"This is the first year such a large disconnect between EV-D68 and AFM has been observed since the association was noted in 2014," she said in an email correspondence with MedPage Today. The 30 cases of AFM confirmed at CDC so far this year is similar to numbers in other non-outbreak years, Routh pointed out.

"Given enteroviruses tend to circulate in the late summer and early fall, we expect we will not see an increase in AFM so late in the year," Routh added. "However, EV-D68 circulation was noted in the winter months of 2021-2022, so CDC remains on alert."

As to why the biennial pattern didn't hold up, "no one knows the answer to this right now," Routh told MedPage Today. "In general, it could be the changes in the virus, host factors, or other co-factors that changed this year to alter the course of AFM," she suggested.

Dr. Amy Moore, of Ohio State Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, who works with patients with AFM agreed that the dip is baffling. "Although we have seen more patients affected than in 2021 and 2022, these are not the numbers that we thought we would see given that children are back in school and masks are not mandatory."

Historical patterns for AFM certainly warranted the warning. AFM has been tracked by the CDC since 2014, when 120 cases were reported in 34 states between August and December. In the following year, there were 22 cases reported, then the number rose again in 2016 to 153 cases.

In 2017, it was down again, with 38 cases; then cases increased in 2018 to 238.

The expectation of a surge had also been high in 2020. In August of that year, the CDC called a press conference warning of an expected outbreak of life-threatening acute flaccid myelitis. In particular, the CDC was concerned that cases would be confused with COVID-19.

"AFM can progress quickly and patients can become paralyzed over the course of hours or days and require a ventilator to help them breathe," Dr. Robert Redfield, CDC director at the time, warned during the briefing. "Some patients will be permanently disabled...The virus most commonly causing this condition, enterovirus D68, tends to come in 2-year cycles. This means it will be circulating at the same time as flu and other infectious diseases, including COVID-19, and could be another outbreak for clinicians, parents, and children to deal with."

However, CDC's 2020 surveillance reported 33 AFM cases for 2020 -- lower than anticipated.

"The low numbers were due to the use of masking and the lack of 'in person' activities due to COVID," Moore told MedPage Today. "This trend was also seen with RSV [respiratory syncytial virus] and flu."

It is now unknown whether the biennial pattern is predictive.

From 2014 through December 1, 2022, the CDC has reported a total of 709 cases of AFM.

Cases of this rare but very serious neurological condition have coincided with respiratory illness caused by EV-D68, the antibodies for which are found in mucous and spinal fluid of some patients with AFM.

Researchers recently reopened the case of a boy who died with AFM-suspected illness in 2008 and found EV-D68 RNA in the anterior horn neurons of his spinal cord. They reported the findings earlier this year in The New England Journal of Medicine, noting that "these findings support the view that EV-D68 infection is a cause of AFM. The pathogenesis of AFM may involve a combination of the direct effects of viral infection of spinal cord motor neurons and damage resulting from local inflammation."

Research is ongoing to better understand the causes and treatment of the condition.

"Right now, CDC is finishing data collection on the confirmed cases and will look at how they compare to cases from previous years," Routh told MedPage Today. "Our partners will be looking at how the virus interacts with their animal models of AFM. We continue to work collaboratively across other agencies and academic centers nationwide to better understand AFM."