Kim Potter trial: Prosecution tears into Potter's police training

Daunte Wright was fatally shot by Kim Potter on April 11.

The prosecution wrapped up its arguments in the trial against Kim Potter, who fatally shot 20-year-old Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in April. In its case, the state is zeroing in on Potter's training as a Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, police officer.

Police officers and use of force experts have been called on the stand one-by-one to analyze Potter's actions.

She is charged with first- and second-degree manslaughter in his death. Potter has pleaded not guilty to both charges.

Wright was pulled over for an expired registration tab and a hanging air freshener in the rearview mirror, police said.

Potter said she meant to grab her stun gun but accidentally shot her firearm instead when she and other officers were attempting to arrest Wright, who had escaped the officers' grip and was scuffling with them when he was shot. He then drove away, crashing into another vehicle shortly after.

Prosecutors argued that regardless of her intent, Potter acted recklessly and negligently. She should have known the difference between her handgun and her stun gun, given her more than 20 years of experience on the force, they said.

They are also arguing that Potter should not have used her stun gun in such a situation since it's against department policy.

Prosecutor Matthew Frank highlighted portions of the training materials that said a stun gun should not be used simply to stop fleeing suspects or on suspects who are operating vehicles. Wright was in the driver's seat of his car when he was shot.

The defense maintained that Potter's actions were a mistake but argued that Potter was within her rights to use deadly force on Wright since he could have dragged another officer with his car.

Sgt. Mike Peterson, a special agent for the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, took the stand as a state's witness. He testified that officers should usually take bystanders, nearby officers, and the scene in the background into account when deciding to use a weapon.

Expert: Unreasonable use of force

Use-of-force expert Seth Stoughton, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law, testified that Potter's use of deadly force was inappropriate.

"The evidence suggests a reasonable officer in Officer Potter's position could not have believed it was proportional to the threat at the time," Stoughton said on the witness stand.

Stoughton testified that deadly force would have been inappropriate even if Potter believed another officer was in the car -- because it could have posed a risk to nearby officers and Wright's girlfriend.

He said any reasonable officer wouldn't have decided to use a stun gun instead of a firearm if they thought there was an imminent threat of death or great bodily harm.

In an analysis of the incident, he also said that "a reasonable officer in that situation would not have believed" those threats existed.

How Brooklyn Center officers are trained

Using pages from the manufacturer's and the department's training materials as evidence, Frank showed the jury that the dangers of mixing up a stun gun and a handgun are discussed at length in the training and certification process.

Potter was trained to keep her stun gun on the holster of her less-dominant side, performing a cross-draw where the dominant hand reaches across the body for Taser, according to former Brooklyn Center Police Chief Tim Gannon.

"The policy was: opposite side of your duty firearm," said Brooklyn Center officer Anthony Luckey, who also testified that Brooklyn Center officers had extensive training on pulling out their firearms and their stun guns. "That way, officers do not get their firearms confused with their Tasers."

He confirmed that officers practice drawing the stun guns, go through slideshow lessons and perform continuous hands-on training regarding their weapons. In addition, they also go through training as not to confuse their weapons.

Sam McGinnis, a senior special agent with the state's Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, led the jury through the Brooklyn Center department's training procedures for using stun guns.

On the witness stand, he showed the jury how "spark tests" are done. He did one with his own device, which generated a loud buzz for five seconds as electricity arced across the electrodes.

Based on department policy, spark tests are supposed to be done at the beginning of every shift to ensure their stun guns are working.

McGinnis testified that Potter didn't test her stun gun on the day she shot Wright or the day before.

She did run the check six out of her last 10 shifts. McGinnis testified that he was unsure of how compliant the department's officers were with the policy.

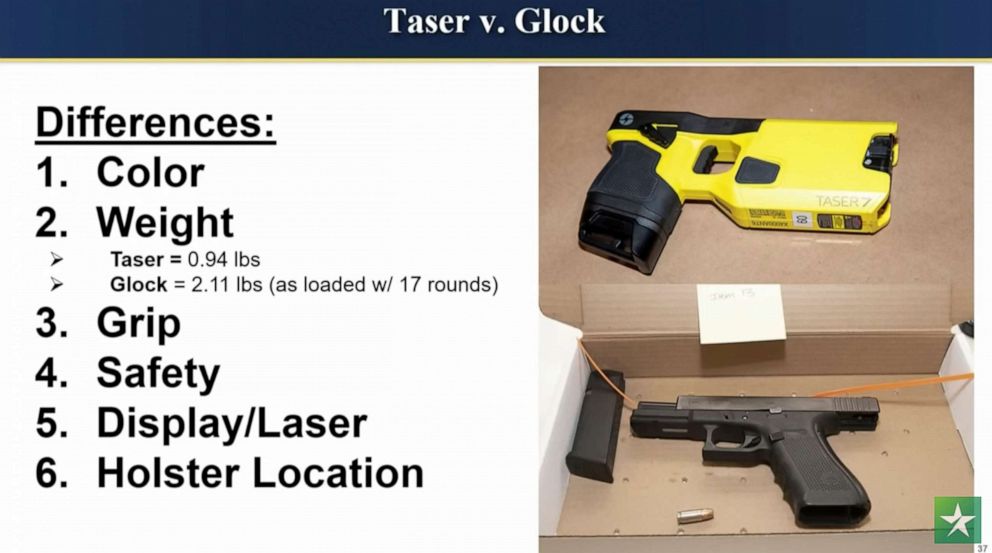

Stun gun versus firearm

McGinnis testified about the differences between stun guns and firearms, as well as how they're supposed to be used. He said that the holsters on Potter's duty belt require an officer to make specific, deliberate actions to release the weapons.

For instance, the Taser holster has a lever, while the handgun holster is closed with a snap.

"Once the Taser is inside of the holster, it's retained there by that security mechanism and can't be brought out again until that is pushed and the Taser's released," McGinnis said.

The Taser is a bright yellow color and weighs just under a pound, McGinnis testified. Potter's handgun was black and weighed over 2 pounds. The Taser and firearm both have different triggers, grips and safety mechanisms that are necessary before they can be used, McGinnis testified.

The stun gun has a laser and LED lights that display before it is fired, and he demonstrated the effects before the jury. The handgun does not have these features.

Stoughton also testified that the dangers of "weapons confusion" are well known.

The defense said it plans on introducing testimony about traumatic incidents, police work and action errors, which defense attorney Paul Engh said will be "about how it is that we do one thing while meaning to do another."

The defense has cited "action errors" as a reason for Potter to reach for her firearm when meaning to grab her stun gun.

"[Testimony] will tell you in times of chaos, acute stress decisions have to be made when there is no time for reflection," he said during the opening statement. "What happens in these high catastrophic instances is that the habits that are ingrained, the training that's ingrained takes over. In these chaotic situations, the historic training is applied and the newer training is discounted."

Engh said that stun guns have only been available in the last 10 years to the department and this is a brand new stun gun, "whereas, by comparison, Potter has 26 years of gun training. And an error can happen."

Stoughton said he knew of "fewer than 20" cases since stun guns entered law enforcement departments in the '90s. Stoughton said stun gun manufacturers have taken several steps to prevent errors, and it's become a vital part of officer training.