Uvalde families find new bond in shared grief, path to healing

Some families have turned their grief into political action.

For the families who lost a loved one in the May 24 mass shooting at Robb Elementary school, the pain is still fresh.

But in that shared grief some families said they've found a bond to help them get through the darkness.

And for some, that grief has pushed them to political action to make sure that no one else has to experience their trauma.

Kimberly Garcia, whose daughter Amerie Jo Garza was one of 19 kids killed in the shooting, along with two teachers, told ABC News she hasn't sought out therapy or counseling because the pain is still too much to bear.

"I wouldn't talk to somebody because then they feel like OK, you accepted it. And so that's, that's very hard for me to do," she told ABC News.

Instead, she and her fiancé Angel Garza have met and spoken with other family members who lost a loved one in the shooting. Garza said those connections have been helping so far.

"We are all in contact with one another and we all talk and we all confide in, with each other. [We] feel each other's pain, and we can understand each other," he told ABC News.

Uvalde:365 is a continuing ABC News series reported from Uvalde and focused on the Texas community and how it forges on in the shadow of tragedy.

Javier Cazares, who lost his 9-year-old daughter Jackie in the shooting told ABC News that he has struggled hard after Jackie's murder. For him and his teenage daughter Jazmin, the most effective way of dealing with their grief was speaking out against the violence that claimed Jackie.

Both have been active in Uvalde, Texas, and Washington, D.C., in calling for gun control policies and holding local officials accountable for what happened. Javier Cazares is now running for county commissioner.

"Yeah, it really has," Jazmin Cazares told ABC News when asked if she felt her activism helped her grief. "Especially with keeping busy knowing with the little changes that have happened, knowing that I was a part of that. I helped do that. I helped maybe even potentially save somebody."

At the same time, the teen said she still gets emotional whenever she visits her sister's bedroom.

"We all have our little moments where we break down, but the fighting [and] the continuous activism has helped a lot," she said.

Since the shooting, several mental health services and organizations have provided affected families and residents with programs.

Near Uvalde's town square, a children’s grief center is a new permanent fixture and offers programs such as pet therapy and group counseling.

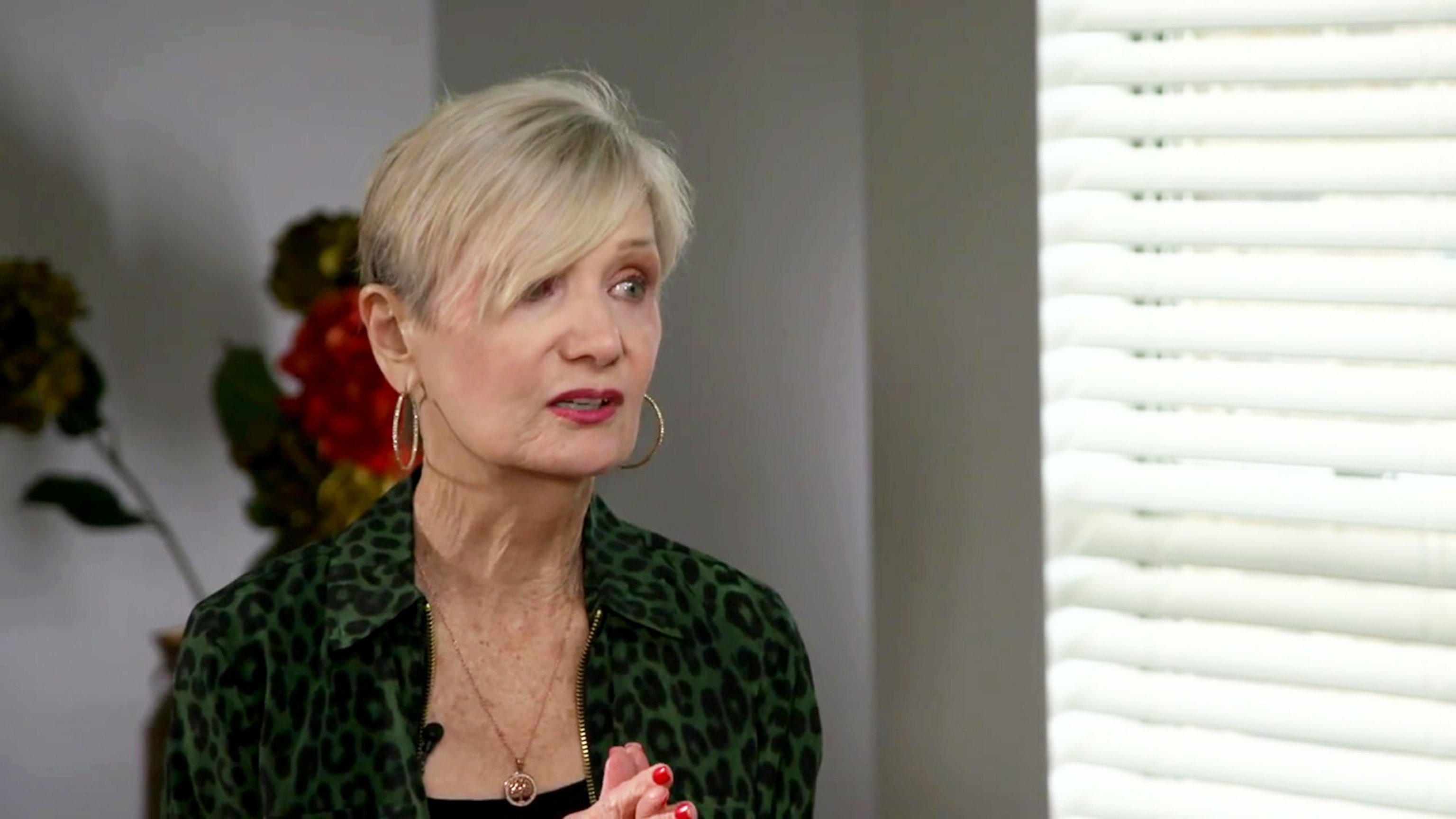

Marian Sokol, the executive director of the Children's Bereavement Center of South Texas, told ABC News that recovering from a mental trauma will take a lot of time. For children, in particular, she said the process won't be linear.

"There is a point over the first year that you have to get through the first birthdays, [and] the first Christmases," she said. "But when a child starts helping another child and taking that pet therapy dog and introducing them to the scared little girl who's just come in the door, then I know we're making progress."

Sokol noted even though it will be an uphill and tough journey, those grieving families will be able to heal.

"I don't like to use the term get over it. We say, 'How do you get through it?' And so I think it's mostly by just realizing that it does take time," she said.